The Storm Before The Storm

Published on September 7th, 2017

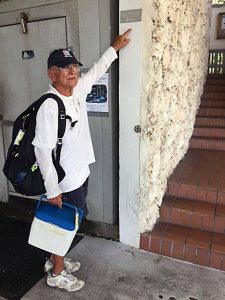

Miami, FL (September 7, 2017) – Richard Crisler remembers Hurricane Andrew like it blasted through his life yesterday. He reaches over his head and points to a plaque on the wall at the Coconut Grove Sailing Club designating the high water mark of the storm surge on Aug. 24, 1992. It is nine feet above the ground.

Biscayne Bay rose up, ripped boats from their moorings and flung them like toys onto Bayshore Drive. His dinghy went airborne like Dorothy’s house in the “Wizard of Oz” and landed at the Coconut Grove Playhouse half a mile away. He recalls seeing nothing but masts poking out of the water, sailboats turned into submarines.

“Once again, we are paying the price for living in paradise, and it is tremendous stress,” Crisler said. “I’m feeling an oppressive sense of dread.”

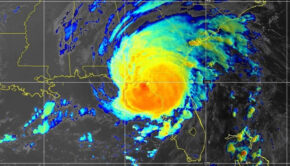

Hurricane Irma is coming, churning through the Caribbean and toward Florida like a Tasmanian devil, a Category 5 monster packing winds of 185 mph. In Miami and all across the state, people are trying not to panic but anxiety is building as they contemplate danger, damage and devastation.

Irma may or may not hit here this weekend but constant reports on the unrelenting power of a storm registering on earthquake seismometers, poignant footage of Hurricane Harvey’s toll and awful memories of Andrew are making it difficult for South Florida residents to think about anything other than the impending threat.

“The best defense, physically and emotionally, is to take action and feel confident that you’ve done everything you can do,” said meteorologist Bryan Norcross, who became the region’s hurricane guru during his nonstop coverage of Andrew. “The forecast puts the dot right on Miami, but don’t look at the dot. Look at the cone. Don’t dwell on the possibility because that’s a vicious cycle of thought. Prepare and you will feel less anxious.”

Rose Healy can’t help but feel anxious. During Andrew, she climbed to the second floor of her Killian house only to see a whirlwind of debris flying through the sky. Her roof was gone. She ran back downstairs, where all the windows were exploding, and was lifted a foot off the floor by a gust as the front door flung open.

She and her sister closed it and held it closed until they thought their hands would break off. Then, with the walls bursting at the seams and the door ripping at the hinges, they and their mother screamed, “One, two, three, go!” and sprinted to the garage, where they huddled for hours.

“Afterward, outside, everyone was walking around like zombies,” Healy said. “People were bleeding, wearing pajamas. Our neighborhood was reduced to a pile of timber.”

So this time, Healy is getting out. She, her husband and daughter are driving to a friend’s house in Chattanooga. Healy, a public school teacher, kept her cool for the sake of her students this week, but she is packing up her Coral Gables house and fleeing. No mas.

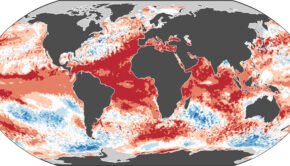

“Two Category 5s in one lifetime — it’s too much and I’m not going to live through it again,” said Healy, who lost everything — her sister even lost her wedding photos — in Andrew. “I have Post Traumatic Stress Disorder from those hours when I thought we would die. In my heart, I’m done with Miami. It makes me sad, but climate change is only going to make it worse.”

Signs of tension — the storm before the storm — are unavoidable: Long lines at gas stations, arguments at grocery stores as customers compete for sparse jugs of water, cars stuffed with precious belongings as highways become evacuation routes, and everywhere the chirping of birds replaced by the sounds of hammers and drills as residents board up their homes.

John L. Alger is bracing for his Homestead farm to be wrecked as it was by Andrew. He’s got 55,000 oak, mahogany, cassia, avocado and palm trees that could be mowed down.

“We’ve got an apocalyptic tornado bearing down on us, and if it’s a direct hit we’ll be flat on the ground and not selling any trees for two years,” he said. “If you survived Andrew, you will never forget the fear. And this thing is so dadgum huge.”

Alger weathered Andrew with 22 people and several dogs in his bathroom. The storm “sounded like a freight train driving through my hallway.” When it passed he had to bulldoze his way out of the driveway. He had no electricity for 46 days. He has a framed photo of a 1-by-6 board piercing a royal palm like an arrow. Three of his 6,000-gallon fertilizer tanks were found a mile away in a field of Brazilian peppers. When the fire alarm and sprinkler system went off in one of his equipment buildings, he invited neighbors to come over and shower.

Although he said it took years to overcome feelings of panic every time a hurricane was lurking, he said he is grateful 25 years later for more accurate forecasting and a revamped building code that resulted in sturdier houses with impact windows. He’s got generators now.

“We’ve had more time to prepare, and I’m proud that we’re getting out front of this one,” he said. “But I’m concerned about my employees, I’m concerned about my grandchildren experiencing the trauma. Resources are stretched because everything is in Houston. We lost 25,000 houses in Andrew. If we get gusts of 225 mph, you might as well kiss your property goodbye.”

Steve Shiver, former Homestead mayor and city councilman and county manager, said Andrew made his city “stronger and more resilient.”

“With Andrew, a lot of people were joking or had a lackadaisical attitude. It was hard to comprehend the magnitude of Mother Nature,” said Shiver, owner of a window and glass business. “This time around, we are overburdened by instant information and fixated on the next update. But we know what to do. I tell people not to be obsessed, be prepared.”

In Miami Beach, extremely vulnerable to flooding from storm surge, residents are debating whether to follow evacuation orders or not.

Marilyn Marcus, who lives in the Costa Brava building on Belle Isle, is departing today. Marcus is reluctantly leaving her condo and joining daughter Rachel in Los Angeles.

“For Andrew, I left Miami Beach and went to a friend’s place in Homestead where we thought it would be safer,” said Marcus, 89. “Instead, it was very scary to be in a shaking house and very grim to see the National Guard on every corner.”

Marcus had impact windows installed two years ago, but doesn’t want to risk getting stranded on the 18th floor.

“It’s a horror to see how they’re suffering in Houston, and it’s going to take a long time to recover, like Katrina,” she said. “They predict Miami Beach won’t exist by the end of the century. Right now, I’m telling people to try not to worry. Don’t bite your nails.”

Her neighbor, Nellie Barrios, is ready to pack up her art and her dogs, pick up her elderly aunt and hunker down in her mother’s house in Kendall.

“People are definitely freaking out but I try to stay calm in a crisis,” said Barrios, a real estate agent. She hid in a closet with three adults and four dogs during Andrew, then worked nonstop as an All State insurance agent. “The industry has changed but it was an open checkbook after Andrew.”

Barrios began to choke up as she recalled handling clients’ claims. In Country Walk, 90 percent of 1,700 flimsily-constructed homes were destroyed. The area was rebuilt and a development called Serenity now stands in the west corner.

“It was heartbreaking,” Barrios said. “Twenty-five years later, we’ve added billions of dollars worth of towers downtown. Centrust was the tallest building and now it’s a midget. So people worry about how we’ll withstand Irma. I tell them, it’s beyond our control, we’ve got to roll with it.”

Ceding control, even in the face of a natural disaster, can stir up another eddy of stress for many, said Dr. Charles Nemeroff, chair of the psychiatry department at the University of Miami’s Miller School of Medicine.

“If you already worry about everything, from North Korea to Donald Trump to Hurricane Jose coming along behind Irma, the best way to cope is to be informed and reassure yourself that the vast majority of people will be OK,” Nemeroff said. “When your heart is pounding or you can’t sleep, take some deep breaths and break the circuit in your head.”

Marilyn Baker is staying put in her Sunset Harbour South condo, where she lives on the 20th floor. Imperturbable, she moved here from Los Angeles, where there is no warning for earthquakes. She’s optimistic the windows will shield her building and the city’s new pump system will function adequately.

“Most of us just stay and have a party in the club room,” said Baker, 83. “I hate to see people overdosed on media coverage, then hoarding and getting greedy and creating shortages of supplies and water. If you’ve been glued to the TV watching Harvey then you’re predisposed to panic. I’m a carry-on type of person. If you live here, then you accept that we’ve got weather in capital letters and you prepare.

“I’m adhering to the first rule of a major hurricane: Eat all your ice cream first.”

Source: Miami Herald

Editor’s note: Our prayers and positive thoughts go out to those in the Gulf that are recovering from Harvey, and to those in the Atlantic regions that have been, or may be, impacted by Irma. With more storms forming in the Atlantic, our thoughts are with you all.

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.