The First Defense of the America’s Cup

Published on August 6th, 2020

by Steven Tsuchiya

August 8th marks the 150th anniversary of the first defense of the America’s Cup (a.k.a. “1st America’s Cup” or “America’s Cup I”). It was a single-race contest won by the yacht Magic, which defeated 16 of her fellow defenders and the lone challenger from England, to complete the New York Yacht Club’s first successful defense of the America’s Cup.

While the race wasn’t fair to the challenger, one may forgive the New York Yacht Club because its members reasoned that a fleet race mirrored the daunting conditions America faced when she took on a comparably-sized group of English yachts in 1851. And to the Club’s credit, they acknowledged their mistake and abolished the format starting with the next match.

The first defense is significant for three reasons: one, it paved the way for future contests for the Cup; two, it set a precedent for using “around-the-buoys” courses for Cup races; and, three, it confirmed that the Deed of Gift, the rules that govern the Cup, could be relied upon to ensure a match would be sailed—even if the challenger and the defender couldn’t mutually agree on the terms for the race.

The first defense, held on August 8, 1870, was a spectacle that made a great impression on both the competitors and the horde of spectators. From that point on, a match for the Cup has taken place on average every 4.3 years.

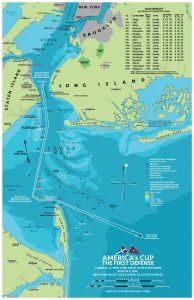

The fleet of Cup yachts competed on a 38-statute mile course from New York Harbor to the Sandy Hook Light Vessel on the Atlantic and return. While the venue and the shape of the courses changed over time (New York and vicinity from 1870-1920, Newport from 1930-1983, etc) they have remained “around-the-buoys” courses of less than 40-statute miles in length.

Had the New York YC accepted the first challenger’s proposal to race over an 80-mile course or an earlier suggestion to race around Long Island, the Cup might have proceeded in a different direction.

The first defense also tested the strength of the Deed of Gift. Prior to the match, the challenger and the New York YC couldn’t agree on the type of yacht to race. Thankfully, a pair of rules in the thoughtfully written Deed of Gift resolved the issue making the match possible.

While the Deed was revised two more times in the 19th Century and amended in the 20th Century, the rules that saved the day in 1870 have endured. These rules rescued the Cup twice again during the acrimonious impasses in the lead-up to the 1988 and the 2010 matches (a.k.a. “Deed of Gift Matches”.)

This is a story of how the Deed of Gift made the 1870 Cup race possible and how Magic won the remarkable race.

THE ROAD to the FIRST DEFENSE

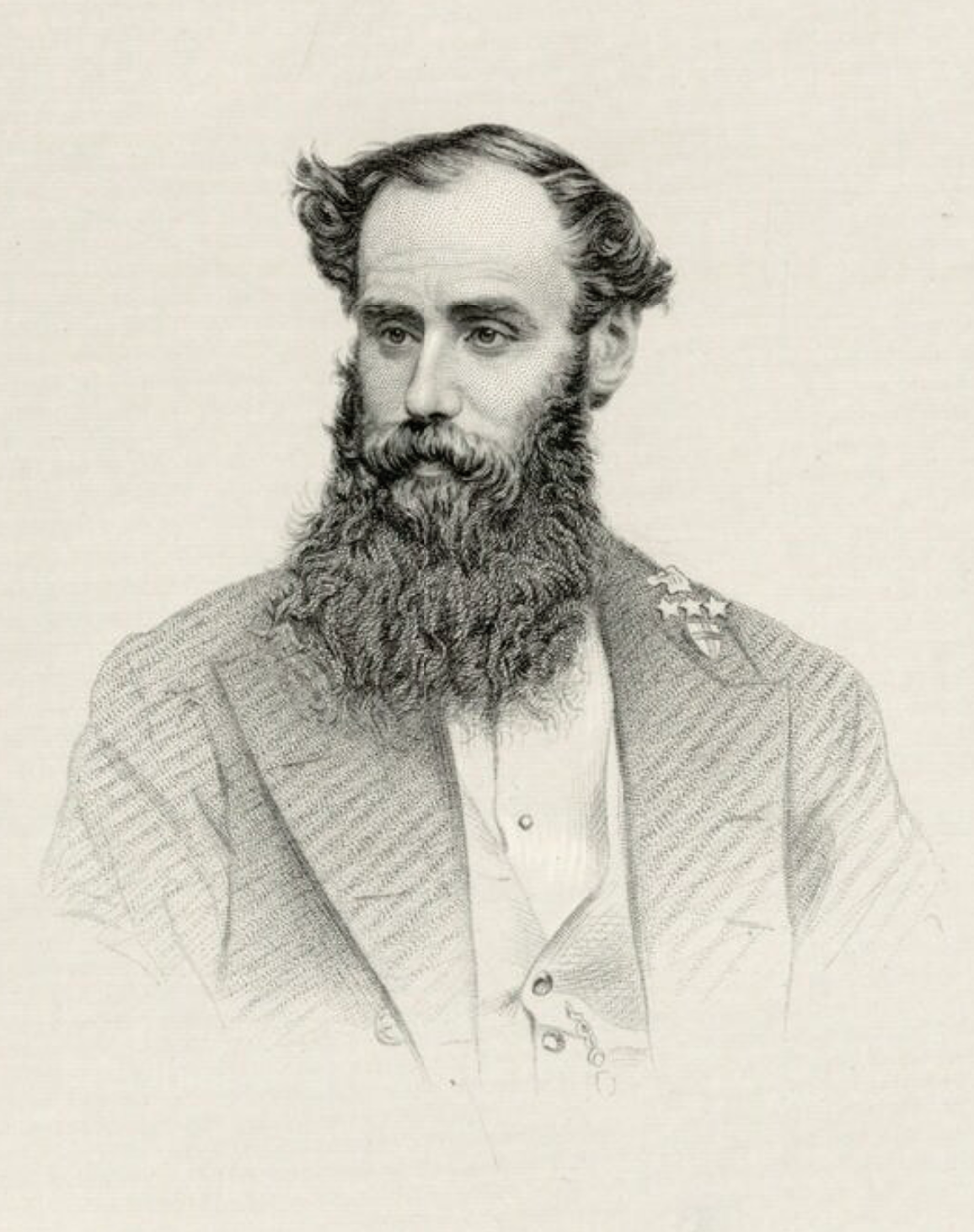

In July 1857, the New York Yacht Club invited foreign yacht clubs to challenge for the Cup won by the yacht America in 1851. But it was over a decade before the Club received its first challenge. That challenge came from James Ashbury, on behalf of the Royal Thames Yacht Club (London, England).

In 1866, James Lloyd Ashbury (1834-1895) inherited his father’s profitable railway-carriage manufacturing business and a large fortune. Since the age of 16, he had worked long hours in the family trade. Ready for a break, he departed smog-choked Manchester for the seaside resort of Brighton.

There, he bought a cruising yacht to take in the fresh air and to advance his social standing in a culture that valued the carefree lifestyle of the gentry over the hardworking industrialist. A contemporary portrait of Ashbury reflects his aspirations: dressed in a reefer and cradling a spyglass, he relaxes at the stern of his yacht, a strong drink, and a plate of grapes by his side.

Beckoned by the racing scene on the Solent, Ashbury soon dumped his cruising yacht and commissioned Michael Ratsey of Cowes to build him a fast racing schooner. In 1868, he took delivery of Cambria, a 227-ton¹ keel schooner of 108 feet in length, stem-to-stern, and a draft of 12 feet.

That summer, he experienced the rush of winning regattas, including a victory over a visiting New York Yacht Club yacht, Sappho, in a race around the Isle of Wight. Emboldened by that win, Ashbury decided to go after the America’s Cup.

After a year and a half of correspondence with the New York Yacht Club, he submitted a challenge on November 14, 1869, writing from the Suez Canal, where Cambria became the first yacht to transit it: “…I give you six months’ notice of my intention to race for the Cup…the course to be a triangular course from Staten Island, forty miles out to sea and back.”² He didn’t elaborate on the strange geometry of the proposed course.

Ashbury also insisted on the following condition: “The Cup having been won at Cowes, under the rules of the R.Y.S., it thereby follows that no centre-board vessel can compete against the Cambria in this particular race…”³

The New York Yacht Club strongly disagreed with Ashbury’s condition because centerboard yachts were qualified to race under its rules. The Club was put into a seemingly tough bind because the Cup’s Deed of Gift prevented it from declining Ashbury’s challenge: the Deed states, “Any organised Yacht Club of any foreign country shall always be entitled, through any one or more of its members to claim the right of sailing a match for the Cup…”⁴

The Deed granted the challenger the inalienable right to sail a match for the Cup, but it also offered a solution to break an impasse if the challenger and the defender couldn’t mutually agree on the terms of the match: “…in case of disagreement as to terms, the match shall be sailed over the usual course for the annual Regatta of the Yacht Club in possession of the Cup, and subject to its Rules and Sailing Regulations…”⁵

It helped that George L. Schuyler (1811-1890), one of the principal authors of the Deed and a member of the America syndicate that won the trophy in 1851, sat on the committee that addressed Ashbury’s challenge. On January 10, 1870, the New York YC committee replied to Ashbury with the solution, sourced from the Deed of Gift:

Dear Sir:

In answer to your communication from Suez, of November 14, 1869, we beg leave again to call your attention to the conditions upon which the New York Yacht Club holds the Challenge Cup won by the America, from some of which there is no power to deviate.

Among others, when challenged by the representative of any foreign yacht club, “in case of disagreement as to terms,” the match is

“to be sailed according to the rules and sailing regulations of the club in possession.” While desirous of meeting your views, as far as possible, in other matters pertaining to the match, under no circumstances can this committee entertain a proposal which excludes from the race any yacht duly qualified to sail under the rules and sailing regulations of the New York Yacht Club.

Respectfully,

George L. Schuyler

Moses H. Grinnell

F. Osgood⁶

Ashbury accepted the committee’s decision. The Club must have rejoiced given the popularity of centerboard yachts among its members. The Deed’s prescription to hold a race “over the usual course of the annual Regatta of the Yacht Club” meant that the race would be held over the New York Yacht Club Course, a 38-statute mile course from New York Harbor to the Sandy Hook light vessel and return. The Club had been using this course for its Annual Regatta since 1865.

At the Club’s second general meeting of the year, on March 24, 1870, its members discussed other points related to the race. They voted on the question of whether to meet the challenger with a single yacht or with a fleet. Commodore Henry Stebbins recommended the former, but his fellow members outvoted him, 18-1, in favor of a fleet. They also decided to make only schooners (keel or centerboard) eligible for the race as opposed to a combination of sloops and schooners as was customary for its Annual Regatta.

To add a sporting element to Cambria’s passage to America, Vice Commodore James Gordon Bennett Jr., owner of the 268-ton keel schooner Dauntless, challenged Ashbury to a race from Kinsale, Ireland to New York. Ashbury accepted the challenge, and on July 4, 1870, Dauntless and Cambria started their transatlantic race.

Most Americans expected Dauntless to win—after all, the legendary Captain Samuel Samuels, who had won the Great Ocean Race of 1866 for Bennett, skippered her. But on July 27, Cambria arrived first, beating her rival by only 1 hour and 17 minutes. The English yacht’s victory heightened the anticipation for the inaugural America’s Cup match.

THE MATCH

August 8, 1870, dawned dark and gloomy over New York Harbor, but by 9 am, the clouds dispersed. At 11 am, 17 schooners of the New York Yacht Club and Ashbury’s Cambria began anchoring about 50 yards apart, along an east-west line in the Narrows.

With the wind from the southwest, Cambria, having been granted the choice of berth, anchored near the weather-most end (west) of the line, with only one boat to her west. The Club’s schooners included the small centerboarder Magic, Bennett’s Dauntless, and America, then owned by the U.S. Navy. America took her place near Cambria. Magic and Dauntless were the fifth and sixth yachts in on the leeward (east) end.⁷

Anchored in the ebbing tide, the schooners pointed toward the city. Their sterns faced the start line, which lay about 500 yards to the south on a parallel line marked by a stake boat on one end and the Club’s Staten Island clubhouse on the other.

Why did the yachts anchor far behind the start line? Because the Deed of Gift authorized that a match—made without mutual consent—must be “subject to [the defending club’s] Rules and Sailing Regulations…”⁸ During that time, the NYYC rules directed second-class sloops to anchor on the start line; first-class sloops to anchor about 250 yards behind the line; and schooners to anchor in the back row, about 500 yards from the line.

Many spectators lined the banks and hills along the Narrows to watch the start, but there were many more of them on the water. Yachting writer Roland F. Coffin, who witnessed the race from pilot boat, observed that other than the possible exception of the ceremonies related to the delivery of the Statue of Liberty, the 1870 race was “the grandest marine pageant ever seen in the harbor of New York. Every schooner-yacht in the Club was entered and started. Nearly every steamer in the harbor was brought into requisition for spectators, and all were crowded to their utmost capacity. Besides these, almost everything that could float, from the large coasting schooner to the tiny skiff, was brought in to use, and it seemed as if the whole population of the city was upon the water. Wall and Broad streets were deserted for the day, and the courts and public office had but few attendants.”⁹

Just prior to the preparatory signal at 11:21 am, the wind shifted to south by east, now placing the boats on the west end of the line—including Cambria and America—at a disadvantage. The start gun roared at 11:26 am, and the schooners raised their sails and weighed anchor as the tide went slack.

The centerboard schooner Magic, with the sailing master Andrew J. Comstock at the helm, “wheeled around as if by machinery”¹⁰ onto starboard tack and was the first yacht to cross the start line; the rest of the fleet turned around over the next several minutes, Cambria two minutes after Magic, and America, just as she did in 1851, starting dead last. The first leg was 9.5 statute miles to windward to Buoy No. 10, off Sandy Hook.

At 89 feet long and 97 tons, Magic was the second smallest schooner in the fleet. However, she took advantage of the handicap system at that time, the Waterline-Area Rule, which did not tax sail area or draft, by carrying an estimated 6,480 square feet of canvas and had draft of 17 feet with her board fully lowered.

Magic’s owner and manager was Franklin Osgood (1828-1888), a mining and zinc manufacturing magnate who had earned fame as one of the organizers of the Great Ocean Race of 1866. During an era when most yacht owners knew little about sailing, let alone racing, Osgood was a bona fide racing sailor.

The New York Herald observed, “Mr. Franklin Osgood, owner of the Magic, is a brave, courageous and bold seaman. He goes for every stitch of canvas aloft in a stiff breeze, and would himself get in the weather rigging if it would accelerate the Magic’s speed.”¹¹

Magic sailed towards Fort Lafayette and, after exiting the Narrows, tacked over to port and was able to lay a course all the way to Dix Island (Lower Quarantine) on the West Bank. The fleet followed. Amid the pack in the Narrows, a large keel schooner, Tarolinta, fouled Cambria, causing some damage to both. But Cambria did not protest.

Off Dix Island, America accelerated with astonishing speed, overtaking one boat after another. America was a crowd-favorite, and spectators cheered on the famous yacht. At 12:48 pm, Magic rounded Buoy No. 10, followed five minutes later by America. At 1:07 pm, Cambria was the 13th boat around the mark.

From Buoy No. 10, the schooners raced on a 9.6-mile reach to the Sandy Hook Light Vessel. With the tide flooding, it was a slog. Dauntless and another yacht passed America while Magic clung to her lead. Coffin writes, “the scene around the lightship when the yachts turned was one never to be forgotten. It would be difficult to estimate the number of people who witnessed the turning, but I know I shall be within bounds if I put it at 20,000.”¹²

At the light vessel, Magic rounded first at 2:03 pm, Dauntless in third, America slipped to fourth, and Cambria improved to eighth position, about 24 minutes behind Magic. On the 9.6-mile return leg back to Buoy 10, the wind began to blow, and Magic covered the distance in just over 45 minutes. Dauntless, with 11,200 square feet of sail area and a 116-foot waterline, gained several minutes on the leader and surged into second, only two minutes behind Magic at the buoy.

Meanwhile, as Cambria passed the Hook, a gust sent her fore-topmast toppling down; despite this, she didn’t lose her position in the fleet.

On the final leg, a 9.5-mile run back to the clubhouse, a 3-knot flood tide helped push the schooners to the finish. Gaining, Dauntless competed with Magic for line honors. At 3:33 pm, Magic finished first, to win on both elapsed and corrected time. Completing the 38.2-statute mile course in 4 hours, 7 minutes, and 54 seconds, she also broke the course record.

Dauntless crossed the line 90 seconds after Magic, but dropped to fifth place on corrected time. America claimed a respectable fourth place. Cambria, the eighth boat across the finish line, placed 10th in the final results. (See the race course chart for the full record of the finishes.)

THE AFTERMATH

While Ashbury didn’t win the match, he earned respect and attention. He was the guest of honor at a New York Yacht Club dinner in Manhattan, and the Club invited him to compete in its regattas in Newport. Ashbury also put up trophies he had brought with him as prizes during his summer-long campaign in America. A highlight for Ashbury and his party was hosting President Ulysses S. Grant aboard Cambria during her visit to Newport.

At the conclusion of the remarkable season, Franklin Osgood sold Magic, likely for a nice premium (as did the owners of America in 1851), to a fellow club member, and he promptly commissioned a new schooner. In February 1871, at a Club general meeting, Osgood was elected Rear Commodore and awarded a silver trophy commemorating his America’s Cup victory.

Ashbury returned in the summer of 1871 for another try for the Cup with a new boat, Livonia. For this contest, the Club, on the urging of George Schuyler, changed it from a fleet race to a match race but reserved the right to select from a pool of four designated yachts on the morning of each race.

The Club also agreed to make the match a best-of-seven series. Osgood and his new schooner Columbia, along with Sappho, defeated Ashbury again, proving that Osgood’s first Cup victory was no fluke. This past February, the America’s Cup Hall of Fame selected Osgood as an inductee of the Class of 2020 for his back-to-back victories.

THE LEGACY

Magic’s victory inaugurated the New York Yacht Club’s incredible streak of 24 successful defenses, from 1870 through 1980, and these defenses subsequently became a major part of the Club’s identity and heritage. Most important, the 1870 race affirmed the Cup’s purpose as a perpetual challenge prize for friendly competition between foreign countries.

*******

Top photo: Great International Race 1870 Currier & Ives Public Domain

¹ All tonnage figures in this article are NYYC measurements.

² Reprinted in the Report of the Committee appointed by H.G. Stebbins, Esq., Commodore of the N.Y. Yacht Club, to take action on the matter of the Challenge of Mr. James Ashbury, owner of the Yacht Cambria, to contest for the possession of The Challenge Cup, won by the America in 1851. New York: NYYC, 1870.

³ Ibid.

⁴ Original Deed of Gift of the America’s Cup. May 15, 1852; re-dated July 8, 1857.

⁵ Ibid.

⁶ Reprinted in the Report of the Committee appointed by H.G. Stebbins, Esq., Commodore of the N.Y. Yacht Club, to take action on the matter of the Challenge of Mr. James Ashbury, owner of the Yacht Cambria, to contest for the possession of The Challenge Cup, won by the America in 1851. New York: NYYC, 1870.

⁷ Positions based on the NYYC Race Committee Reports, edited by William U. Swan. Reported positions of the yachts vary from source to source.

⁸ Original Deed of Gift of the America’s Cup. May 15, 1852; re-dated July 8, 1857.

⁹ Roland F. Coffin. The America’s Cup, How it was won by the yacht America

in 1851 and has been since defended. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1885. Pages 36-37.

¹⁰ New York Herald. “1851-The Queen’s Cup-1870.”August 9, 1870. Page 3.

¹¹ New York Herald. “Yachting Notes.” May 16, 1870. Page 7.

¹² Roland F. Coffin. The America’s Cup, How it was won by the yacht America in 1851 and has been since defended. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1885. Page 39.

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.