Why This Hurricane Season Has Been So Catastrophic

Published on September 24th, 2017

After Harvey, Irma, and Maria, Michael Greshko (National Geographic) looks at why this hurricane season has been so active.

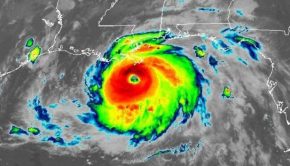

Just as Hurricane Harvey wrapped up its devastation of Houston, Irma got into line behind it and quickly built into the strongest Atlantic hurricane in recorded history. Now, Maria leaves a broken Caribbean in its wake: Dominica’s rooftops and rainforests have been ripped to shreds, and Puerto Rico may be without power for months as a result of the storm.

It’s hard to avoid comparisons to the last time two such powerful storms threatened U.S. landfall in the catastrophic 2005 hurricane season, 12 years ago.

As in 2005, when Katrina and Rita devastated the Gulf Coast in rapid succession, the country is staring down the barrel of multiple hurricanes making landfall. In the face of multiple major storms, a reasonable person might wonder why this season seems worse for U.S. cities, and why the last dozen years brought fewer large hurricanes to U.S. shores.

How active was 2017’s hurricane season forecast to be?

Above average. The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Colorado State University, and the Weather Channel all estimated that this year, we’d likely see more hurricanes than usual spawning in the Atlantic Ocean. NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center forecasted that we’d see between 14 to 19 named storms and five to nine hurricanes this season. In comparison, the average hurricane season from 1981 to 2010 featured 12 named storms and six hurricanes.

Why is this season so active?

In short, atmospheric conditions were hurricane-friendly, and surface sea temperatures were warmer than usual. The Climate Prediction Center says that multiple conditions, such as a strong west African monsoon, have aligned to make the Caribbean Sea and part of the tropical Atlantic, a storm-spawning area called the “Main Development Region”, particularly well-suited to hurricanes.

Kerry Emanuel, an atmospheric scientist at MIT who studies hurricanes, says that two factors stand out. For one, there’s currently little difference in wind speeds near the surface and those roughly 10 miles up, which ensures that miles-tall hurricanes can form and remain stable. What’s more, the tropical Atlantic is exhibiting high “thermal potential,” meaning that water can rapidly evaporate into the atmosphere.

“Thermal potential is a thermodynamic speed limit on hurricanes,” Emanuel says. “The greater the speed limit, the more favorable conditions are for hurricanes to form, and the more powerful they can get.”

What’s more, El Niño is stuck in neutral this year, improving Atlantic hurricanes’ prospects. When this warming of the equatorial Pacific is active, there tends to be more wind shear and less thermal potential over the Atlantic, hurting hurricanes’ chances of survival.

Was there really a “drought” of hurricanes for more than a decade?

The phrase “landfall drought” refers to the fact that before Harvey, it had been nearly 12 years since a hurricane rated Category 3 or above made landfall in the U.S., going back to Hurricane Wilma in 2005. Depending on how you define a Category 3 hurricane, this stretch had been the longest since at least 1900.

What caused the drought?

Largely, it’s an artifact of how we measure hurricanes. As Hart and colleagues demonstrated in a 2016 study, if you slightly tweak the definitions of hurricane categories, the “drought” mostly vanishes.

For the full story, click here.

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.