All is Lost: Behind the scenes making of the film

Published on October 10th, 2013

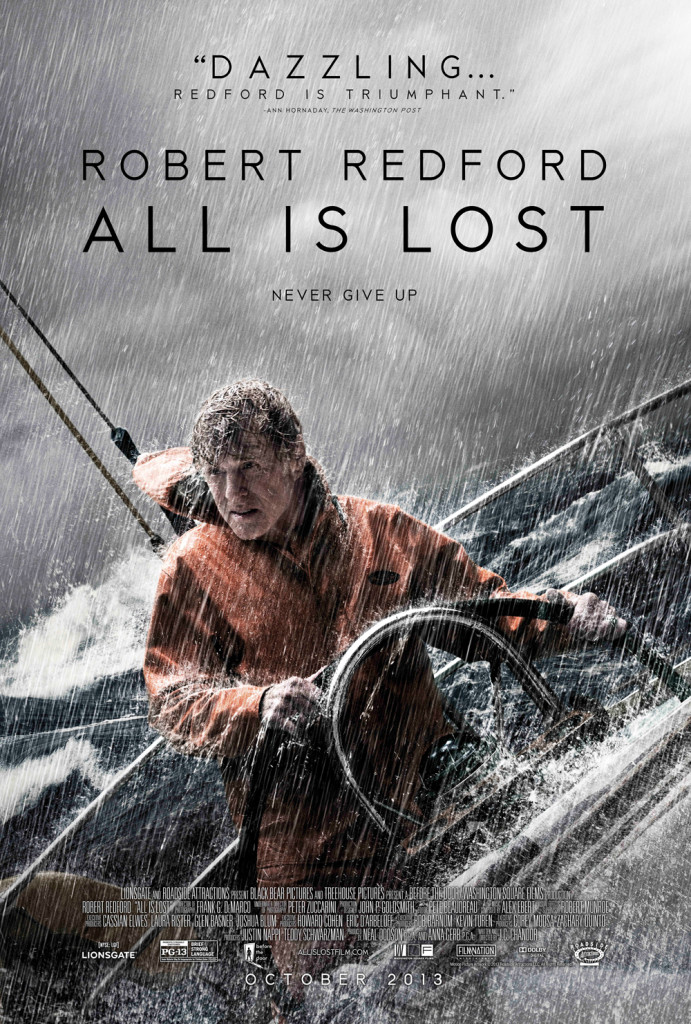

The latest sailing theme movie hoping to make a big splash – All is Lost – will be released in New York and Los Angeles on October 18, and then in over 200 cities throughout the United States in the following week. Here are the movie’s production notes which provide some of the nuggets about the behind the scenes making of the film…

ALL IS LOST – SYNOPSIS

Academy Award® winner Robert Redford stars in All Is Lost, an open-water thriller about one man’s battle for survival against the elements after his sailboat is destroyed at sea. Written and directed by Academy Award nominee J.C. Chandor (Margin Call) with a musical score by Alex Ebert (Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeros), the film is a gripping, visceral and powerfully moving tribute to ingenuity and resilience.

Deep into a solo voyage in the Indian Ocean, an unnamed man (Redford) wakes to find his 39-foot yacht taking on water after a collision with a shipping container left floating on the high seas. With his navigation equipment and radio disabled, the man sails unknowingly into the path of a violent storm. Despite his success in patching the breached hull, his mariner’s intuition, and a strength that belies his age, the man barely survives the tempest.

Using only a sextant and nautical maps to chart his progress, he is forced to rely on ocean currents to carry him into a shipping lane in hopes of hailing a passing vessel. But with the sun unrelenting, sharks circling and his meager supplies dwindling, the ever-resourceful sailor soon finds himself staring his mortality in the face.

Lionsgate & Roadside Attractions, Black Bear Pictures and Treehouse Pictures present a Before The Door/Washington Square Films Production. Robert Redford in All Is Lost. The director of photography is Frank G. DeMarco and the underwater director of photography is Peter Zuccarini. Production designer is John P. Goldsmith. Editor is Pete Beaudreau. The music is composed by Alex Ebert. Visual effects supervisor is Robert Munroe. Executive producers are Cassian Elwes, Laura Rister, Glen Basner, Joshua Blum, Howard Cohen, Eric D’Arbeloff, Rob Barnum, Kevin Turen, Corey Moosa and Zachary Quinto. The producers are Justin Nappi and Teddy Schwarzman. Produced by Neal Dodson p.g.a. and Anna Gerb p.g.a. Written and directed by J.C. Chandor.

ABOUT THE PRODUCTION

Filmmaker J.C. Chandor knew he wanted to make some form of open-water thriller long before his feature writing and directing debut, Margin Call, was nominated for a Best Original Screenplay Oscar®. But it took almost six years for him to finally hit upon the startlingly original idea for All Is Lost, a harrowing nautical adventure that takes place entirely at sea and features a single nameless—and nearly wordless— character.

“It’s a very simple story about a guy late in his life who goes out for a four- or five-month sail,” Chandor says. “Fate intervenes, the boat has an accident, and essentially we go on an eight-day journey with him as he fights to survive.”

Chandor’s screenplay bore little resemblance to a typical movie script. Rather than the standard 120 pages, it was roughly 30 pages long. And it consisted entirely of prose description, with no dialogue. In fact, when Margin Call producer Neal Dodson got his hands on the slim sheaf of papers, he asked Chandor when he would receive the rest of it.

“When J.C. said that it was the whole script, I was both terrified and excited,” Dodson recalls. “The first film we did together was all about dialogue, and this was very obviously not about dialogue. I admit that my first thought was, ‘I don’t know how the hell we’re going to get this thing financed’—because it’s pretty audacious and pretty brave.”

Fellow producer Anna Gerb (Margin Call) recalls reading the script on her deck with Chandor present, and being blown away by the sheer viscerality of it.

“I read it and I looked at J.C. and said, ‘Wow. I’m seasick,'” she recalls. “As a producer, I like to be in control. Being in the middle of the ocean on a sailboat, putting myself in a situation where I am at the mercy of the universe is something I just couldn’t imagine. ”

Chandor, on the other hand, was intimately familiar with the universe of sailboats.

“Although I never sailed across the ocean alone, sailing is something I grew up around,” he says, “so I knew the basic palette I was working with.”

Chandor says the sheer simplicity of the story—and the filmmaking challenge it presented—drew him to make the film. The story has echoes of Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea, and as Dodson describes “it’s an existential action movie about one man lost at sea, fighting against the elements and himself.”

A pivotal step in the film’s journey from script to screen was, of course, the casting of two-time Academy Award winner Robert Redford (The Sting). The iconic actor, director and creator of Sundance had met and been impressed with Chandor when Margin Call premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in 2011.

“I liked J.C. Chandor,” Redford recalls. “He represented, for me, the exact type of person that we want to support. He had a vision, he was a new voice on the horizon and he told his story in a very special way.”

When Chandor told Dodson that he wanted to cast Redford as the film’s sole character, referred to simply as “Our Man” in the script, the producer knew it was a longshot.

“I said, ‘Listen, he’s going to say one of two things when he gets that 30-page script,” Dodson recalls. “He’s either going to say, ‘Hell yes, this sounds amazing,’ or he’s going to say, ‘Why in the world would I do that? I have nothing to prove. Why would I put myself through that?’ And to our great, great benefit, he said yes.”

For his part, Redford was drawn to the originality of the project, which he describes as a story about a man who takes “one heck of a journey and one heck of a beating.”

“I really liked the script because it was different,” Redford says. “It was bold. It was eccentric, and there was no dialogue. I felt that J.C. was going to go through with that vision, even though it was not all explained.

But I trusted that he knew what he was doing, that he had it in his head. I knew I would be supporting that vision even while not knowing everything, and that was interesting and good for me.”

Perhaps surprisingly, Redford says he doesn’t get bombarded with invitations to star in the movies of the independent filmmakers he champions. Quite the contrary, in fact.

“There’s something kind of ironic in that, all these years after starting Sundance and starting the film festival, none of the filmmakers that I supported ever hired me,” he says, then adds jokingly: “They never offered me a part! Until J.C.”

With their one-man cast in place, the producers sat down with the list of necessities for shooting the film. At the very top: a handful of sailboats, and a place to sink them. As it turned out, shooting the story of one man and his boat actually required three boats—specifically, three 39-foot Cal yachts. While all of them serve as Our Man’s sailboat, the Virginia Jean, each of the three boats was used for a separate purpose: One was for open sea sailing and exterior scenes, another was for the tight interior shots, and the third was for special effects.

Finding three similar boats proved to be a challenge, however, says production designer John Goldsmith, whose previous credits include No Country for Old Men and The Last Samurai. “We scouted them at different times and purchased them in different ports. They all had to be imported, which was a logistical exercise in itself. I think we were two weeks into prep before all three were side by side, ready for us to work on.”

Once they had them, the filmmakers put the boats through their paces—and then some. “We did pretty much everything that you can do to a boat on film,” Chandor says. “We sunk it, brought it back to life, sailed it, then put it through a massive storm, flipped it over, and sunk it again. I think it’s paramount to have a pretty deep understanding of the way these boats work, the way they sail and sink, as well as all of the different kinds of sailing elements we use to help move the story along.”

Chandor and Goldsmith collaborated closely in crafting a kind of back story for the boat itself, which in turn helped inform the story of Redford’s character.

“J.C. and I had some fantastic conversations about what story we wanted to tell about Our Man that would be expressed through this boat,” Goldsmith recalls. “What kind of past has he had? Was he a military man? Is he a businessman? Is he a family man?”

Goldsmith says Chandor gave him detailed notes to guide the production design. For instance, the director told him he envisioned Redford’s character bought the boat at age 51, six years after the boat was built. Ten years after that, the boat’s upkeep may have slipped a little due to the economic slump in the 1990s. Painting the back story in even greater detail, Chandor envisioned that Redford’s character retired seven years after that, then invested about $20,000 in updating the boat.

“So maybe he selected certain things like the cushions, which were tired, and reupholstered those,” Goldsmith explains. “Maybe he upgraded the window treatments, maybe a few pieces of electronics. So there’s this idea of layering of time and history in this boat. But it’s not an overhaul. It’s not a renovation. In that way, the design had to be really careful about not coming too far forward, but being sort of quiet.”

Given the solitary nature of the film, Chandor, at times, lets his camera linger on Redford and relish his quiet, simple activities in a way seldom seen on film.

“It’s rare to watch someone think,” Dodson observes. “Most movies are very ‘cutty,’ and I enjoy those movies. But this isn’t that movie. Yes, it’s got action sequences, but the camera is going to sit on him for a while. We’re going to watch him eat a can of soup, and watch him have a glass of bourbon, and watch him cook, and watch him stand in the rain.”

In one memorable scene, the sailor is chest-deep in water collecting supplies from his slowly sinking yacht. Then he takes a break to stand before the mirror and—for possibly the last time in his life—shave.

“You work against the odds in the weirdest ways,” Redford says. “But when the odds are so great against you, you fight hard to create some normalcy in your life, even though it may seem weird.”

Other scenes were intensely physical for the actor, who is known for doing many of his own stunts: from clambering up the sailboat’s 65-foot mast to being dragged behind the boat to swimming underwater through the submerged sails. And then there’s the opening sequence in which the sailboat collides with the shipping container and Our Man jumps from one to the other.

“We slammed a boat into the side of a shipping container with him on it—that’s in the movie,” Dodson says. “There’s this huge jolt, and that’s Bob actually hitting the side of a boat and being okay with it. We put him in a life raft and flipped him upside down and inside out, and he was game.”

“Whenever he did his own stunts, it was both inspiring and exciting, and it also put a little fear in us,” Gerb adds. “But he is in great physical shape. He loves the water and he loves to swim. There are a lot of physical challenges in making this film. Even just being wet all day is exhausting and physically draining on any actor. But his spirit and his understanding of the vision for this film just took over. He came to the set every day and absolutely gave himself over to the process of making this film.”

For his part, Redford says he greatly enjoyed working with the director, whom he credits with getting the best out of him as an actor.

“I’m doing this because of J.C.,” Redford says. “I like him. He has a joyous spirit and a wonderful disposition. But the thing that’s incredible is how busy his mind is. It’s a quicksilver mind, and I find it really fascinating. I think he will do very well, because he knows what he wants and he knows how he wants to get it, but he stays loose through the process, which I think is wonderful. He’s very intuitive, he has a vision, and I trust him and his ability to deliver that vision.”

Chandor’s use of digital effects was largely restricted to enhancing backgrounds and skies, as well as enhancing the waves that surrounded the boat and hammered Redford’s character. All visual effects work was handled by a team at Toronto-based SPIN VFX, overseen by Chandor and longtime VFX supervisor Robert Munroe (X-Men).

Filming in water is notoriously challenging, and that was certainly the case with All Is Lost, which does not feature a single shot set on dry land. Camera crews filmed in various parts of the Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean, including off the coast of Ensenada, Mexico, about 80 miles south of San Diego. At one point, Redford sailed the Virginia Jean into port there, complete with a patched-up hole in the side of the boat.

“It was amazing to see the reactions of real sailors in the marina,” says Gerb. “They were looking at our boat, which had clearly been through an incredible battle. It had a film crew hanging off of it and Robert Redford at the helm.”

The shots of sea life—including shoals of small fish, yellowtail, barracuda and the beautiful if terrifying shots of dozens of swirling sharks—in the Bahamas, off the coast of Nassau and Lyford Cay, where an entire camera crew dove down more than 60 feet to capture the footage of the fish.

For the sequences involving the massive shipping vessels, the crew filmed in the ocean around Los Angeles—out of the port of Long Beach to the south, and further north near Catalina Island.

But the open ocean is no place to safely sink a yacht. For those scenes and a number of others, including the opening collision with the shipping container, the filmmakers turned to the world’s largest filming tanks. Baja Studios, located in Rosarito Beach on Mexico’s Baja Peninsula, the facility was effectively built from the ground up by James Cameron, who required a customized water environment to shoot the spectacular nautical effects for Titanic. In fact, some of the crew on All Is Lost had also worked on Titanic, including line producer Luisa Gomez da Silva, who works full time at the facility and counts herself part of “the Titanic generation.”

The filmmakers used three giant water tanks for different aspects of the shoot, including the world’s largest exterior tank, which sits right on the ocean and has an infinity-edge horizon line.

“It’s the size of three football fields and it creates a very real ocean look,” Gerb says. “These tanks mimic being out at sea, but in a controlled environment where we could safely pull off a lot of our stunts and special effects. It was really the only place in the world we could have made this film.”

Initially, Chandor and Goldsmith believed they would have all they needed with the three boats, but one particularly dramatic sequence, in which the storm-tossed Virginia Jean repeatedly capsizes and rights itself, called for extraordinary creativity. Although the filmmakers had thought they could use the special-effects boat for this underwater rolling stunt, after further exploration they realized they needed to better protect Redford. As a result, multiple departments pulled together to build a special rig for the purpose.

Similarly, special effects supervisor Brendon O’Dell (Training Day) had to come up with creative solutions to simulate the violent movement of the boat in the storm. “Typically, on a big-budget movie, you’d build a really elaborate gimbal that could move the boat in any direction,” he says. “But that would have been very expensive and time consuming, so we had to rethink our approach.”

Instead, O’Dell’s team used simple rigging and hydraulic cylinders, together with the natural buoyancy of the boat working against the water. “We would just suck the front of the boat down with a cylinder and let the back up, and vice-versa,” he says. “It also worked side to side. It looked really good.”

The complex shoot required seven weeks of meticulous preparation—unusual for a small, independent film. “We needed to create a schedule that tracked wet scenes, dry scenes, storm scenes, with three boats, three tanks and an additional sound stage, night and day, stunts, VFX shots and non-VFX shots,” Dodson says. “It was a lot more complicated than anything I’ve ever worked on before, and enormously complex for a 30-day shoot on our budget.”

The producer says the crew worked less from the script than from a big map in their main conference room on which the entire movie was storyboarded.

“We didn’t really even have sides,” he says, referring to the daily printouts actors usually use. “We used a printout of that day’s storyboards—we’d just go through them and shoot them.”

To capture All is Lost Chandor turned to not one, but two directors of photography—Frank G. DeMarco and underwater cinematographer Peter Zuccarini. For DeMarco, the challenge of shooting a movie without dialogue was not without silver linings.

“One interesting thing is that you can do far more takes on a movie with less dialogue,” says DeMarco, who also worked with the director on Margin Call. “The other interesting thing is that, like in a silent movie, the director can sometimes direct the actor during the take. J.C. could actually say, ‘Bob, now remember this, and then do that, and pick up that, and look up there,’ while the camera was rolling.”

DeMarco says shooting interior shots in the tight space of a yacht’s cabin was also tricky—for example, when Redford had to squeeze past the camera on DeMarco’s shoulder or during very close shots.

“We shot with wide lenses, which helped a lot,” DeMarco recalls. “We used a lot of natural light. Ultimately, we just made it work.” If some crewmembers found themselves having to contend with water, others thrived in it—and none more than Zuccarini, whose credits range from low-budget surfing documentaries to the seafaring blockbuster Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl.

“He and his team know how to get in their wetsuits, seal up the cameras, balance their weight and their breathing, and swim in and under the water, shooting footage that you can’t believe,” Dodson says.

With its smorgasbord of water-related challenges, All Is Lost was an irresistible project, says Zuccarini. “I specialize in putting cameras in places that are very wet. So when I saw from the very first moment of the script that there’s water flowing into the boat, he’s immersed in water, water is going to spray on his face, waves are dumping on him—I admit, I was pretty excited.”

Adding to the production challenges, editor Pete Beaudreau (Margin Call) did the first pass of editing on location to ensure that the production got what it needed. After a rough start, he says he got used to the approach.

“Because I was able to get the material so quickly, I could show J.C. at the end of the day whatever he had shot that morning, all put together,” Beaudreau says. “And if he felt like he was missing something, we could go in the next morning and grab it.”

In a film so devoid of dialogue, the musical score assumed special importance. Chandor turned to acclaimed singer-songwriter Alex Ebert, leader of the band Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeros, to compose the film’s score—his first such project.

“It was sort of a shocker in some ways,” says Ebert. “It’s amazing that J.C. would have that kind of faith in someone who hadn’t scored a film.”

Ebert says Chandor initially asked him to deliver very subdued materials, drones and low notes that sustained over scenes. He also specifically requested that the instrumentation avoid piano. That was challenging for the composer, who had already written some pieces on piano, but he understood Chandor’s reasoning.

“The piano has this inherent emotion to it,” he says. “We didn’t want anything that was ’emotion in a can’ or ‘tension in a can.’ But eventually I started taking more chances, and after some back and forth with J.C., we landed in this middle spot that I think was perfect.”

Ebert says he played various instruments, including synthesizer, crystal bowls and Tibetan bowls. He also played orchestral samples, most of which were later replaced by musicians using real instruments. Other times he came up with themes on the piano, then mocked them up with sampled flutes or other sampled instruments, before bringing in great musicians to play them. Seth Ford-Young, the bass player from the Magnetic Zeros also provided a number of sounds that evoked the calls of whales and other sea mammals.

“The biggest challenge was walking that fine line between truth and melodrama,” Ebert says. “You don’t want to undershoot it and you don’t want to overshoot it. You want to nail the emotion precisely. Anything else is not doing it justice.”

For Ebert, All Is Lost is an inherently emotional film with massive stakes, and he felt he needed to express that in the music.

“It’s about beauty,” he says. “It’s emotional and everything that comes along with life and death, and nothing less. I think that’s the primary subject of humanity—and it’s something that you might want to stay away from because it would be overdramatic. But this dude’s in the middle of the ocean on a raft. Let the music be emotional because it is emotional. We followed the movie’s lead.”

The task of building a robust soundscape for an almost dialogue-less film on the sea fell to the Oscar winning sound team behind such hits as Saving Private Ryan and Jurassic Park, Richard Hymns and Gary Rydstrom, along with their colleagues Steve Boeddeker and Brandon Proctor, from Marin County’s famous SkyWalker Sound. They had already worked on several films with Redford in the director’s chair and welcomed the chance to work with him again.

In some ways, All Is Lost is a tribute to man’s seemingly limitless ingenuity and resilience, with Redford’s character simply refusing to quit.

“This character keeps going to a point when some people would give up and say, ‘It’s too much,'” Redford says. “‘I’m out in the middle of nowhere. No one is here to help me and it seems like I’ve done everything I possibly can. Why not give up?'”

To answer that question, Redford references an earlier film whose sparseness and primal simplicity have something in common with All Is Lost and in which the actor plays another lone man battling nature and self.

“I thought about Jeremiah Johnson, about that film and that character, especially since I had developed that project myself,” says Redford of the 1972 film. “He had a choice to give up or continue but he continues, because that’s all there is. And this film, I think, suggests the same thing. He just goes on because that’s all he can do. Some people wouldn’t, but he does.”

It’s in those moments of maximum anguish that Our Man actually breaks his pervasive silence and utters a word or two—to great effect.

“There’s a scene where we finally hear the iconic Robert Redford voice,” says Gerb. “There is no real dialogue to speak of in the film, but in this one moment, for a very brief second, he says something. And to hear his voice, and how it comes out, is so powerful, because we all know that voice. And then it comes, and it’s this tiny beat, but it’s a very moving moment for me.”

For Dodson, it is precisely the drive to survive—even when all is apparently lost—that gets to the heart of the film’s meaning.

“It’s a movie about why we keep fighting,” Dodson says. “It’s a movie about why we try to live—about why we would fight against death when it seems so obvious that it’s our time to go. Answering that question about human beings is something philosophers, religion and great thinkers have been trying to do as long as humans have been on earth. I think this movie tries to ask that timeless question in a new way. And for my own part, I’m far more interested in going to see movies and making movies that ask questions than in movies that propose to answer them.”

It’s also part of what makes the film unlike any other, the producer says.

“I don’t think you’ve ever seen a movie like this before,” Dodson says. “It’s a truly singular vision. It’s watching one guy—a master of his craft—work through a character in 90 minutes. And it’s an adventure. But the existential questions in it, I think, will resonate for people even more powerfully.”

As for Chandor, he says he hopes audiences will see themselves reflected in Redford’s valiantly struggling survivor.

“What I’m hoping,” Chandor muses, “is that this character becomes a vessel where audience members are able to see themselves, or parts of themselves. That he becomes the embodiment of some of their hopes, concerns, dreams, worries, fears—all those primal human characteristics. It’s not something that I want to lay out too explicitly, but to a certain extent, I hope that he can become a kind of mirror. And if I did my job well, the film, like Our Man’s journey, is going to be exhilarating and terrifying, and, I hope, emotional and haunting.”

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.