When the wave hits and the tether snaps

Published on August 9th, 2020

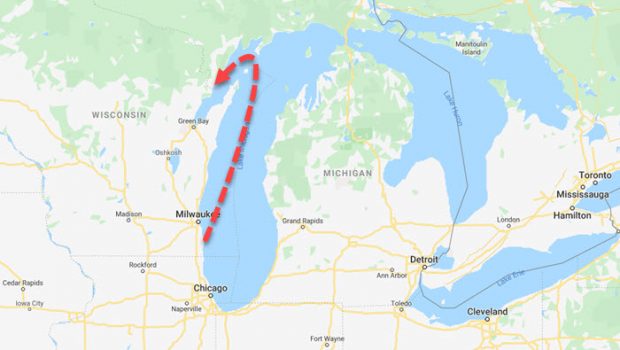

The 37th running of the Racine Yacht Club HOOK Race on July 18 was a 189 nm course from Racine, Wisconsin, up the western shore of Lake Michigan, and “hooking” through Death’s Door, a narrow and often treacherous passageway between Washington Island and Wisconsin’s Door County peninsula, into Green Bay, and ending in Menominee, Michigan.

The race promotes the “challenge of the Door of Death.” Legend has it that a raiding party of Potawatomi Indians all perished when their war canoes capsized in a squall on their way to the Door peninsula to engage the Chippewa in battle. Nobody could have foreseen at the start of this year that the challenge for the HOOK race and race committee would be much greater than navigating Death’s Door.

With a limit of 100 boats to participate, storms led to significant attrition: 4 withdrew, 5 did not start, and 29 did not finish. There was also an overboard story told by Sarah Pederson who was swept off the J/111 Shmokin’ Joe five miles northeast of the shipping channel in Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin:

This wasn’t the first time I had participated in “The HOOK” race. The race itself began in 1983, I have participated in 23+ races, and it wasn’t any different than the others I participated in. As in other years, we can’t control the weather and this year wasn’t any different.

The forecast for that weekend was 15-20 knots of winds from the South/Southwest and thunderstorms. To a sailor, that is ideal conditions to “fly” up the lake to our finish.

My sailing experience began early on. Sailing was our “family sport”. Our father introduced all six of us at an early age. I personally have been active in the sport of sailing for 55 years as a racer, instructor, presenter, and supporter of the sport. With my husband, over the past 32 years we have owned and raced boats carrying on the tradition by teaching his two sons how to sail and race.

So, what happened? There were two thunderstorms that we were tracking throughout the day on Saturday, July 18th. The fleet had already sailed through one off Milwaukee. We experienced some of it north of Milwaukee, off Fox Point as we sailed along the northern edge of the storm. From reports, other boats were not as lucky and experienced the full storm causing boats reporting dismastings.

As we continued our trek north toward Death’s Door Passage off Gills Rock in Door County, Wisconsin we continued to track storm #2. This storm appeared to be stronger and didn’t seem as though it was dissipating throughout the day. We tracked it as it traveled across Lake Winnebago and made it way toward Lake Michigan.

As the track came closer and we could now see the lightning associated with this storm, as a crew, we began to prepare for the storm. Our preparation included reducing our sail area by taking down the mainsail and raising the smallest jib available. We insured that all crew members above (4 crew members) and below deck (4 crew members) were wearing US Coast Guard approved life jackets, a safety harness, 6-foot tether, along with a strobe light, whistle, and sailing knife.

When the storm started to affect the boat the wind began to increase. Even though we had reduced sail area we could feel the effects of the increase. Eventually, the wind hit us with a gust of 50+ knots. There were some on the race that reported 60-70 knot gusts. At the time of the gust, there was a wind shift causing the boat to auto-tack and round up leaving the crew now on the low side of the boat.

When this happened a wall of water came rushing down the deck picking me, and another crew member off the deck. Because we were all wearing a safety harness and six foot tether, the “theory” is we would have stayed with the boat and would have been “retrieved” by pulling on our tether.

This happened to the other crew member, but not to me. While my tether strap stayed strong (purchased in 2017, not one of the 2010 tethers that were recalled), my tether snap shackle at the chest position, for whatever reason, opened which sent me off the boat and into Lake Michigan in the middle of a thunderstorm, 50+ winds, 5 foot waves, 56º water, and 60º air temperature.

The mayday was called by a crew member monitoring both the storm, as well as, our navigation, notifying the US Coast Guard, Sturgeon Bay Wisconsin of the MOB. This crew member remained monitoring the radio throughout the rescue.

When I bobbed up, free of the boat, I could see the boat in a pinned down position. It has been reported to me that the boat remained in that position for up to six minutes. But almost immediately I lost sight of the boat due to the conditions which caused limited visibility.

My first thought was I was grateful the water wasn’t as cold as I thought it would be. I had heard all week the Lake Michigan temperature was unseasonably high (70º) for that time of the year. Unfortunately, as it was explained to me after the incident, the water had a “turnover” from the waves, change in wind direction, and storms which dropped its temperature.

Because I did not have any time frame for the events of the night, I do not know what order I had done any of these actions. I turned on my strobe and pulled out my whistle that was on a lanyard around my neck. I blew my whistle several times but then realized using the air to blow was challenging. I would use the whistle sparingly. I kicked off my sea boots and crossed my arms across my life jacket and held on.

At one point during the time in the water, I did see two boats in the distance – the J/111 with their spotlight panning the water for me, and the US Coast Guard with their red illuminated side panels. At that point, I felt as though they were moving away from me.

I was wearing a full lifejacket, not an inflatable, and my choice for a full lifejacket was a conscious one. I have said that I feel as though, in my situation, the full lifejacket saved my life.

The waves were measuring 5 feet at the time of the storm and I needed to float like a cork, to bob up and down. As the waves would crash over me I would rotate my body so that I would take the wave from my back. I learned this early when I had taken a few mouthfuls of water in my mouth and nose. I didn’t think that would be a good thing for an extended period. When I would rise onto the top of a wave I would attempt to extend my strobe higher in the air for better visibility.

I chose to wear a regular lifejacket at night for the warmth and comfort factor. I have often said that I don’t think I would want to go overboard at night in an inflatable to reduce the chance for mechanical failure. I do wear an inflatable, I was wearing one during the day.

I realized to survive this, I would need to regulate my breathing. There was a lot of self-talk happening while in the water, the first thing I said to myself was “You know what to do, this doesn’t have to be the end.”

I will say that the self-talk throughout the hour being in the water wasn’t always so positive but for the most part I had the skills to hang in there. I felt as though my ability to swim – what I have been calling water awareness was a big part of being able to tread water for about an hour. I knew I had the skills to do this…

I had no idea how long I was in the water until the J/111 that I was sailing on heard my whistle and then saw my strobe. Luckily, the storm had started to move out making visibility greater. This assisted greatly in their ability to find me. The US Coast Guard was right behind them. As I understand, the Coast Guard search pattern is in a square, narrowing in on the last known location. They did their job to perfection.

Once aboard the J/111, I was transferred to the US Coast Guard vessel in a basket with the potential of hypothermia. With Emergency Medical Services waiting for me at the station, I was transferred and then taken to Door County Medical with a diagnosis of mild hypothermia. I didn’t have any other reported injuries so my treatment consisted of a warming blanket and a bag of warm saline.

This story is about a lot of very skilled, experienced, and prepared sailors who handled an emergency with precision. It is about being prepared. Prepared for a storm, all equipment was accounted for before we even left the dock the morning before with the skipper/owner checking to make sure all crew had all the required safety equipment.

It is about knowing what to do in the water as well as on the boat. This story is about wearing a lifejacket. It doesn’t make any different what you choose to wear. I wouldn’t be alive without it.

This story is about how lucky I was to have the US Coast Guard so close to provide the needed support.

WEAR YOUR LIFE JACKET, ATTACH A WHISTLE TO IT, IF OUT AT NIGHT, HAVE A STROBE OR SOME OTHER DEVICE THAT WILL BE USED AS A VISUAL. ALL WILL SAVE YOUR LIFE!

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.