Tokyo 2020: Unlocking the secrets of Sagami Bay

Published on August 19th, 2020

Success at the Olympics is the convergence of all the variables. While ability and speed are the foundation, going fast in the wrong direction doesn’t do much good, so understanding the winds and current in Sagami Bay is a massive piece of the puzzle.

However, that’s easier said than done, but when the postponed Tokyo 2020 commences next year in Enoshima, standing on the podium will require all the puzzle pieces.

“We’ve done it a little differently each quad,” admitted US Olympic team head coach Luther Carpenter. “In this quad, we’re going back to a meteorologist-based program. But it’s always been tricky to find the right person to lead that and also the person that has the right skills, the right experience, and the right energy to interface with the coaching staff and athletes.

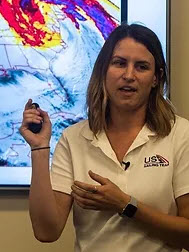

For Tokyo 2020, that person is Chelsea Carlson, a degreed meteorologist and lifelong sailor, who in 2019 founded SeaTactics to provide expert weather knowledge to racers who want to elevate their sailing strategies to gain a competitive edge.

“We’re very excited to be working with Chelsea,” noted Carpenter. “She’s a new find for us and is a very knowledgeable and enthused meteorologist who loves to go on the water, who loves to talk sailboat racing. She’s a sailboat racer herself. And we’ve enjoyed two summers in Enoshima with her already and have developed quite a good system and way of interacting with her.”

For Chelsea, she’s pretty excited too.

“I feel very lucky doing a job which includes two different things I love, which is the science-based approach of weather forecasting combined with being on the water in a competitive environment, “explained Carlson.

“After spending so much time on the water, and then combining that with what I know to cause the various features and shifts and clouds, I am now in a position to teach that to the team. My goal is to impart that knowledge onto the sailors and the coaches.

“But there’s always an element of uncertainty because we all want to know what’s going to happen before it happens, which is a pretty tall ask. So it becomes this balance of painting the picture but then knowing where to live within that picture because it’s not always going to be how we think it’s going to be.”

For a venue that has demonstrated both light and variable offshore winds and blustery onshore weather, developing the playbook is no small task.

“With any venue that’s in a semicircle type of a bay, there’s obviously geographical features which become very important,” describes Carlson. “Then you also have oceanographic features like the water temperature or major currents.

“In Tokyo they have the Kuroshio, which is an analogue to the Gulf Stream as it’s not too far offshore, and that influences the weather a little bit. And then there’s your typical sea breeze versus gradient wind, standard stuff.”

With such a difference in conditions between the onshore and offshore breeze direction, what are the odds of one over the other?

“In the summers that we’ve been there, it seems to be a good mix, so in that respect it’s been interesting,” noted Carlson. “There’s also been a few typhoons that have hit when we were there which makes it very dynamic. It’s almost like Miami or South Florida in the summer, with lightning storms and the threat of hurricanes playing havoc on a sailing venue.”

For the Rio 2016 Olympics, there were seven race areas – four within Guanabara Bay and three outside the Bay – with each demonstrating unique characteristics. But Carpenter sees the Tokyo 2020 venue as even more challenging.

For the Rio 2016 Olympics, there were seven race areas – four within Guanabara Bay and three outside the Bay – with each demonstrating unique characteristics. But Carpenter sees the Tokyo 2020 venue as even more challenging.

“In Rio, it was a pretty bankable sea breeze that came down the bay,” said Carpenter. “That wind was much more stable, I think, than what happens in Enoshima.

Enoshima has a very similar wind direction every day when it’s from the south, but what we’ve been learning from Chelsea is the causes of those different winds are very subtle. So we need a better understanding of what’s causing it, because even though we’re looking at the same compass rose numbers, the wind can have a different characteristic.

“In Rio, we didn’t have a meteorologist on site, but we hired Dave Dellenbaugh to help us write this playbook. Part of the magic of writing a playbook is that you have to create it, and for me and for most of our coaching staff in Rio, the exercise of creating it meant we really didn’t even need to look at it by the time we got to the Olympics because we already knew it so well.

“Preparing for 2020, it’s a similar exercise we’re doing with Chelsea except we are finding the winds and current to be more complex than Rio, so we are placing more emphasis towards the weather side of things in Enoshima. Working with Chelsea, she is this young person that is into interacting with us and has that magical spark of, ‘We all want to learn it together’.

“As a result, that makes us just a much better machine on how we interact together. When we wake up in the morning and see how it is a southeast gradient, and what that should mean, Chelsea helps us figure out at the debrief after three days of that on how our knowledge of that condition needs to evolve and requires more study, or how we can gain confidence in how our knowledge matched up with the observations.”

But being wrong is part of the job, and despite the available tools, weather forecasting remains as much art as science. Balancing that reality, while building trust with the coaches and sailors, puts Carlson in a precarious position.

“Yes, it’s part of the territory as you’re never always going to be right when trying to literally predict the future,” recognizes Carlson. “So you just take it with a grain of salt. For me, personally, the biggest motivator is not in always wanting to be right, but is just understanding why. So on a day that the forecast didn’t go as planned, I go back and I find out why – what happened?

“It is after digging in, and working with the sailors, we can put the pieces together. No one expects you to be right 100% of time. We’re all human. And we’re trying to do a very complicated science, but I think understanding even in hindsight helps build the confidence.”

In the absence of providing a perfect timeline of what to expect on the course, Carlson seeks to instill in the sailors the skills needed for them to anticipate and adjust to the conditions they are experiencing.

“I ask a lot of questions to the sailors because, ultimately, being a sailor, I know that you actually feel more about the shifts, and you’re looking at the compass when you’re in the sailboat,” she acknowledges. “If I ask them a lot of questions. I get them to look beyond the boat.

“By asking, ‘What do you think about those clouds over there?’ it begins a conversation in which I can help guide them to understand what’s happening. I see that’s one thing that might be lacking in a lot of youth sailing as there’s not a big focus on educating about clouds or the weather or even just sea breezes. So just understanding the basic mechanisms that are affecting the wind goes a long way.

“There’s a lot of very advanced sailors in which forecasting is not a strength, so it is needed to educate as much as you can, and then when they’re on the water, I just try to get them thinking about what they see. Of course, there’s days that we don’t think too much about the weather because they’ve got enough on their plate, and it’s more important to focus on speed or equipment, but if it’s appropriate, then we’ll talk about clouds or weather.”

As coach boats get geared up with instruments to support her mission, Carlson ultimately does not see technology as the deciding factor for Tokyo.

“There’s always a lot of cool weather tools out there, and while we have some in our toolbox, I think when points are close and the race is tight, what each sailor decides to do with the knowledge they have in their brain is what’s going to win the race. That’s what wins medals.”

Editor’s note: Chelsea is providing a promotion for Fall race forecasts. For details, click here.

Olympic Sailing Program

Men’s One Person Dinghy – Laser

Women’s One Person Dinghy – Laser Radial

Men’s Two Person Dinghy – 470

Women’s Two Person Dinghy – 470

Men’s Skiff – 49er

Women’s Skiff – 49erFx

Men’s One Person Dinghy Heavy – Finn

Men’s Windsurfing – RS:X

Women’s Windsurfing – RS:X

Mixed Multihull – Nacra 17

Original dates: July 24 to August 9, 2020

Revised dates: July 23 to August 8, 2021

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.