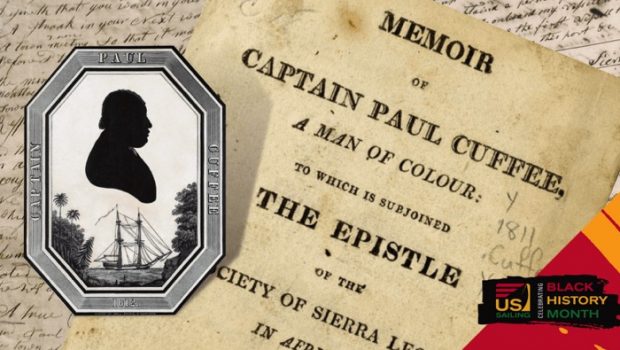

An American icon: Paul Cuffee

Published on February 10th, 2022

February is Black History Month in the United States, and in this report by US Sailing, they recognize one of the notable contributors to African-American sailing history:

Transatlantic voyages aboard self-made ships. blockade running under the dead of moonless nights. A wildly successful shipping business. A groundbreaking push for equality and a dream of Pan-Africanism, nearly a century before Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation.

How could you not know about this American icon, right?

While it may seem improbable, this is the story of Paul Cuffee, among, if not the richest black man in America during his life; the son of an enslaved man and Wampanoag woman who made his fortunes sailing the New England coast and the Atlantic.

Cuffee (often spelled with only one e) was born in 1759 on Cuttyhunk, the last in the Elizabeth Islands chain, eleven miles off the coast of New Bedford. His father, Kofi Slocum, was a formerly enslaved Ashanti man, freed by Quakers from whom he took his last name; his mother was a Wampanoag native woman from Cape Cod. When he reached adulthood, he dropped Slocum as his last name and adapted his father’s Ashanti first name instead, Anglicizing the name Kofi to Cuffee.

At an early age, Paul Cuffee showed an interest in boatbuilding, navigation, and trade inherited from his father. As a teenager, he built small boats and traded among the Massachusetts islands, taking his first job on a ship at the ripe age of 14. He and his brothers also assumed farming and landowning duties on the family property in Dartmouth, MA, from their father when he passed away.

Even as a young man, Cuffee never accepted the status quo when it came to his power as Black man. When Cuffe was 20, he and his brother John petitioned the Massachusetts government for the right to vote, arguing that as landowners and taxpaying citizens, they had the right to representation. While the petition was at first denied, that right was enshrined in the Massachusetts constitution written a few years later.

After handing farming duties over to his other siblings, Cuffee took to the sea. In 1776 he took a job aboard a whaling ship owned by the Rotch family, notable Quaker merchants and whalers of New Bedford. It was during this time that Cuffee had his first encounter with the British as the Revolutionary War gathered steam.

That same year, his ship was captured by the British Navy as they travelled through New York. Cuffee spent three months in a British prison before being released. This encounter inspired Cuffee to take up the cause against the British, using his navigational and ship building knowledge to penetrate the British blockade of Nantucket and bring much-needed supplies to residents of the island.

Cuffee performed his daring runs, done under moonless nights to avoid capture, throughout the war years. They helped him build a trade network in the Islands and gain the trust of residents who would later become important business partners. By the end of the war, few had as extensive knowledge of the currents, shoals and patterns of the Massachusetts Islands as Cuffee.

After the Revolutionary War, Cuffee continued building his family and maritime empire. In 1783, he married Alice Pequit, a Wampanoag woman from Martha’s Vineyard. During that same time, encouraged by Quaker friends he made during the war, he and his brother-in-law established a shipping company and boatyard, and began sailing New England with ships crewed mainly by Black and indigenous sailors.

Besides being a trailblazing mariner, Cuffee also used his influence to enact change for Black Americans. He used his position as a respected businessman to establish several public works projects, serving not only the Black community, but anyone in need of support.

When he wanted to send his children to school to learn to read and write, both skills Cuffee had to teach himself, he offered to build the first public school in Westport, MA. His neighbors scoffed at the idea of having their children sit next to Black students, so he opted to build the school on his own property, welcoming local children of all races. Thus, Cuffee established what was possibly the first integrated school in the US.

Besides his work at home, Cuffee was also a pioneer abolitionist, admired across the Atlantic. Using his connections in the maritime industry, he became involved with British abolitionists set on establishing a successful colony of formerly enslaved people in Sierra Leone. Using his wealth and donations from other American Abolitionists, Cuffee helped fund some of the first “Back to Africa” emigration in the US.

Cuffee also advocated for the industrialization of native Africans, being the son of an Ashanti man himself. He advocated for the establishment of trade ports, farming systems, and ship building facilities. Cuffee’s efforts became one of the early glimmers of the Pan-Africanism, a movement aiming to encourage and strengthen bonds of solidarity between all indigenous and diaspora ethnic groups of African descent, that would come into popularity in the 20th century.

When he died of illness in September of 1817, he was a wealthy, well-respected man in politics and business. At his funeral, Reverend Peter Williams Jr., Minister of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in New York City, who had been a close friend for many years, eulogized Cuffee, “Captain Cuffee was a judicious and a good man. His thoughts ran deep, and his motives were pure.

“Such was his reputation for wisdom and integrity, that his neighbors always consulted him in all their important concerns, and, oh, what honor to the son of an African slave, the most respectable men in Great Britain and America were not ashamed to seek to him for counsel and advice!”

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.