Lesson learned the hard way

Published on April 25th, 2022

Last summer, Mary Kay Dessoffy encountered Lake Erie at its worst and shares this lesson learned the hard way:

Lakewood Park, just a little west of downtown Cleveland, is the locals’ hot spot for Lake Erie gazing and watching the sunset. Ohio lake lovers perch themselves on the solstice steps and turn their attention to the western sky to watch the fading pink and orange circle fall into the calm waters of Lake Erie.

While the sunset is predictable in its sameness, Lake Erie’s shallow waters are fickle and can quickly shift from a mere ripple to rolling white caps. Love our lake if you must, but those who do, know that she is a cantankerous paramour, and a powerful wind shift from south to east will get her all riled up, making her a formidable opponent rather than a sailing buddy.

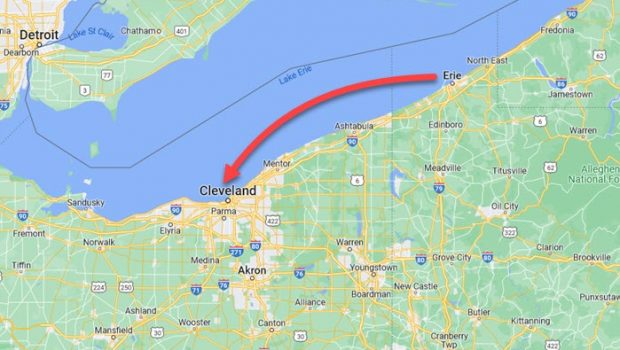

Unstable Northeast Ohio weather last July canceled a handful of our sailing dates out of Cleveland, but our crew of three—my brother Joe, husband Dan, and I– hedged our bets anyway and drove to Erie, Pennsylvania to close the deal on a 2003 Hunter 35.6 and sail her home. We arrived at the Erie Yacht Club on a rainy Friday afternoon, intent on a shake-down cruise in the bay before venturing out the following day.

But straight-away, the problems presented themselves.

The furling main was jammed mightily in its position in the mast, and a quick glance at the owner’s manual revealed it was not wound into the mast in the right direction. It took some poking and prodding, tugging, and pulling to convince the cranky main to come out and play, but, when furling it back into the mast, we had to pay close attention.

Sailboats, with myriad lines leading back to the cockpit, have a way of showing you who’s boss when the weather gets moody, and this led to our second opportunity to improve. With the wind building we were eager to pull the sails in, but one of our crew, in his haste, freed the main halyard instead of the sheet.

So instead of drawing the main in tighter, the head of the sail lowered itself obediently a couple of feet. After scrambling to winch it back up (and get back into the dock), we labeled the deck-mounted clutches so there would be no question on each line’s task.

With the sails all furled in, and the Yanmar diesel at the ready, we motored back into the dock while the wind continued to build. As the helmsman circled toward the dock, the wind, now gusting, shoved the boat away, and we made another approach. And another. And another.

The boat showed us who was boss when we put her into reverse and she moved her stern assertively to port. Prop walk. Richard, the previous owner with his wife Julie warned us about this, but experiencing it is another story. We would learn to use this to our advantage.

Because Lake Erie has conditioned me to expect her worst behavior (and be grateful for her best), my own pre-shake-down cruise started days before. I learned how to use a sea anchor and made sure we had one on board. Most importantly, I studied each harbor between Erie and Cleveland in case we needed to tuck in fast.

Our deep-draft sailboat would need to tread lightly in shallow harbors like Conneaut or the Chagrin Lagoons, but had water to spare in Ashtabula, Geneva, and Mentor. My matrix, folded neatly into onboard paper charts, included phone numbers, fuel availability, and water depths, with a special note for Conneaut’s shallow harbor: “Avoid.”

Friday night and Saturday morning, the three of us watched the weather forecasts with the intensity of teenagers playing games on their cell phones. Skies were overcast, the winds calm, and the forecast giving a 60% promise of clear skies by two o’clock. Despite the sixth sense we had that bad weather was a good possibility, we all had a case of the “Get There-itus.”

We decided to cast off.

Under full sail and light air in the Presque Isle Bay, a protected six square mile sailor’s heaven, we headed out on the lake. An hour or so later, however, the once-gentle wind picked up behind us, and a while later the water rolled in like giant barrels. A drenching splash over the starboard side was fair warning to pull the sails in.

The main rolled up easily, thanks to the previous day’s shake-down, the furling foresail became a storm sail, and the diesel hummed along nicely. We considered turning around, but we were too far into our journey to make it worthwhile; and while conditions were uncomfortable, they were still workable. We expected the weather to improve as the day wore on, just as the forecast predicted.

But during the next hour, on our way to Ashtabula (or so we thought), a good six or seven hours away at this pace, the wind was howling with gusts, the following sea rose higher than Dan’s 6’2” height in the cockpit, and rollers bullied our starboard hindquarters into portside rolls.

I remember Richard telling us, “She has always kept us safe,” and I was taking that to the bank. In fact, the boat was behaving with more courage than I could muster, as she was patiently climbing, falling, and listing leeward. This was not mere discomfort any more, and it was hardly tenable for us sailors even if the boat exuded patience.

Joe, expecting the best, was dressed in shorts and a pullover tee, and he was soaked but unwilling to go below for his storm gear. He said would rather freeze to death than have to lean over the side or, God forbid, go below to unload his breakfast, and I couldn’t blame him.

Just a tad protective of my little bro, and only a little green around the gills myself, I dashed below for his storm pants in the V-berth (of course), and not finding them in a few seconds opted to grab Dan’s spare storm pants just before getting thrown into the door of the head and earning a purple goose egg on my arm.

Although Dan and I were wearing storm gear, the water had penetrated even that. It was unanimous. We needed to tuck in well before Ashtabula.

The nearest port was, naturally, Conneaut, the shallow harbor on my matrix with the caveat “Avoid.” We would go to Conneaut. I radioed Conneaut that we were a 35-foot sailboat in distress, and the dock master, Don, said he could accommodate us but that he leaves at 3:30pm.

I panicked quietly, gave him our location, and sounded about half as desperate as I really was. We entered Conneaut Harbor hours later at 3:45pm. I called on my cell phone and Don answered. “Well,” he said, “I couldn’t just go and leave you out there, so I waited.”

Conneaut’s protected harbor calmed the waves while the fierce wind still had its way with our freeboard, but our relief at hearing Don’s voice on my cell phone and, at last, out of Lake Erie’s grip, banished our fears of someone getting tossed overboard. Now, we were more worried about running aground.

I took my cellphone in the cockpit to talk to Don and relayed the information to Dan, who was fatigued from helming this entire journey, yet unwilling to entrust us with the task. The wind howled over Don’s voice and I caught a word here and there. I heard “Green shirt. Waving.”

I took the phone into the companion way to get out of the wind, only to be greeted by the roar of the diesel, returning then to the cockpit just as I heard Don yell, “No! Go west! Shallow…” I screamed at Dan while motioning frantically with my left arm to the portside, “West! Shallow here!” I scanned the shoreline, and there he was, Green Shirt Don, waving us safely into the Conneaut entrance.

It took Don and three of his buddies to wrestle us into the dock. Once again, the wind shoved us away from the dock, which was at our starboard side. We tossed our dock lines to four pairs of waiting hands, the guys snugged them, stepped on the working end, snugged them more; and the forward prop walk came in a tad handy, too. More or less.

While the prop walked the stern toward the dock, the wind shoved the bow away from it. The arduous process of tying up took about 15 minutes, plenty of muscle, and, unfortunately for Don, a laceration (that didn’t require an ambulance) on his hand. It marked the end of an eight-hour debacle of motoring, and at that point, I didn’t care if I ever sailed a boat again. I changed my mind of course.

A couple of days later, we heard from the yacht broker who told us she and a captain friend of hers watched us leave the Erie Pennsylvania harbor. Her friend, in the business of towing boats back to shore, remarked dryly, “Well, there’s one I’ll be bringin’ back.”

Not today, Captain. This will make for a good, very true, a story of a lesson learned the hard way. But a radio call and stern warning would have been nice.

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.