Deep dive into scoring systems

Published on May 19th, 2022

When Lee Morrison got involved in the administration of his local fleet’s summer series, he was surprised by the division about which scoring system was better. Wanting to understand the reasoning behind the debate, he wrote this report to document his discoveries:

After taking on scoring for my local fleet, we began to debate which average point scoring system is best. Spoiler alert: best is in the eye of the beholder. So, here’s a mathematical comparison for a logical discussion.

Background: scoring systems based on average points are used when competitors don’t expect to sail in every race in a series. With average scoring a boat’s series score isn’t impacted when it doesn’t sail. At the end of a series the boat with the best average score wins – typically after participating in a minimum number of races.

There are three popular average scoring systems: Low Point, High Point, and Cox-Sprague. We focus on High Point and Cox-Sprague because Low Point scoring, although the simplest of the three to use, generates the same score for a finish position regardless of the size of the fleet.

Intuitively, we believe doing well in a big fleet is more difficult than in a small one and the scoring system should reflect that.

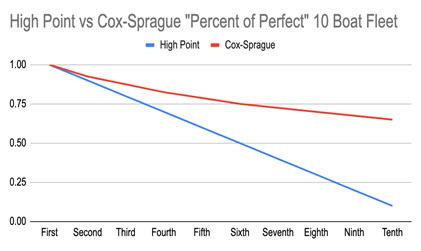

The core difference between High Point and Cox-Sprague is how individual race scores are determined. High Point uses a formula (number of boats beaten + 1) and Cox Sprague uses a lookup table.

Mitigating the absolute difference in Cox-Sprague and High Point scores is that the score is only part of the calculation in determining a series average. Individual race scores need to be converted into a value that represents the boat’s finish relative to the other boats in the race.

This value, called the “Percent of Perfection” (PoP), is the boat’s score divided by a perfect (first place) score for that race. So, regardless of the method used to determine the score or size of the fleet, the winner of a race always gets a perfect PoP of 1.

When plotted on a graph, as shown below, High Point PoPs are linear whereas Cox-Sprague PoPs form a less steep, slightly curved line. The PoPs in a High Point race are evenly distributed across all finishes. With Cox-Sprague, poorer finishes get relatively higher (less worse) PoPs compared to better finishes.

The result is that when using Cox-Sprague scoring, a boat’s series average is less impacted by poor finishes than it would be when using High Point scoring.

To determine the overall series PoP, the PoPs from each race are averaged together. (Technically, to avoid averaging an average, the sums of the individual race scores are divided by the sum of the scores for a perfect finish in the races that the boat sailed.) At the end of the series,the boat with the highest average PoP – the boat that finishes closest to perfect in each race, on average – is the winner.

So, what does this mean in practical terms? Let’s make up some finishes in a fictional series that highlights the differences between Cox-Sprague and High Point scoring. In this simple example, six boats sail in four races allowing us to throw in a simple (not average) low point score for comparison. I used the new raceScore App to do the scoring. It’s easy to generate both High Point and Cox-Sprague scores from the same set of finishes using raceScore.

Under both Low Point and High Point average scoring systems, boat 202 wins. However, with Cox-Sprague, boat 101 comes out on top. 101’s poor 6th place finish in race 4 doesn’t impact the overall Cox-Sprague average as much as it does under High Point (or straight low point).

It’s the same situation with the 3rd and 4th place boats. 310’s relatively poorer finishes in races 2 and 3 doesn’t negatively impact 310’s Cox-Sprague series score as much as it does under the other scoring systems. Or, in other words, 330’s more consistent performance is overshadowed by 310’s first place in race 4. A scoring system that penalizes poor finishes relatively less, rewards good finishes relatively more.

Scores for boats 320 and 340 exhibit the same fundamental difference – they’re tied under Low Point and High Point systems with the tie breaker going to 320 because her 3rd in race 2 beats 340’s best finish in any race (e.g. 320 and 340 have the same number of firsts and seconds – zero. But, 320 has more 3rds and wins the tie-breaker). However, with Cox-Sprague, 320 gets a higher score outright – no tie.

To summarize, when choosing a scoring system for a long running series, either Cox-Sprague or High Point work well to rank competitor’s finishes even when the competitors may not compete head to head in every race.

If your Fleet prioritizes individual race performance, then Cox-Sprague rewards better finishes by not penalizing poor finishes as harshly as High Point. On the other hand, if consistency is valued, then High Point is a better choice.

Rewarding individual race performance was the philosophy behind Olympic scoring years back. A first place in an Olympic fleet came with a huge scoring bonus. With increased challenges of running races for larger fleets, an emphasis on consistency discourages competitors from trying high risk, high reward tactics.

In balance, experience shows that the differences between High Point and Cox-Sprague are subtle. The winner of a series is typically the same regardless of the scoring system chosen. Other variables (available in raceScore) have a more significant impact on overall results. And, the use of throwouts can help influence the scoring system chosen.

The qualification percentage variable plays a big factor. When set too high, it reduces the number of boats that will qualify to be scored in a series. If too low, some competitors may be more picky in determining when they’ll sail knowing that they can easily qualify.

But, a low qualifying percentage may also encourage a competitor to participate even if they know that they will miss many races in the series. A good compromise seems to be 50% – that is a boat needs to sail in half of the races in the series to qualify for awards.

As mentioned, the use of throw-outs, because they encourage taking risks (knowing that a mistake can be discarded), can be used effectively to balance out High Point’s slightly greater emphasis on consistency.

Throw-outs, when based on the number of races sailed, also encourage participation. In our fleet we set the throwout parameter to 4 – meaning that one additional throw-out will be rewarded for every four races sailed after qualifying.

Average scoring systems are great for frostbite or season series run over many weeks making it difficult for competitors to participate in all races. The complexity associated with computing average scores are eliminated with programs like raceScore.

Then, when the scoring job becomes as simple as entering finishes onto a spreadsheet, the Fleet scorer’s happiness and longevity will increase! And, competitors appreciate seeing weekly results and knowing how they are doing during the series.

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.