When things go wrong

Published on November 22nd, 2022

The biennial Transpac Race extends on a 2225 nm course from Point Fermin in Los Angeles to the finish line off Diamond Head in Honolulu, Hawaii. It cuts across a big ocean, and when things go wrong, the distance from either the start or finish lines is the closest point of land.

Alan Blunt shares a story of when things go wrong:

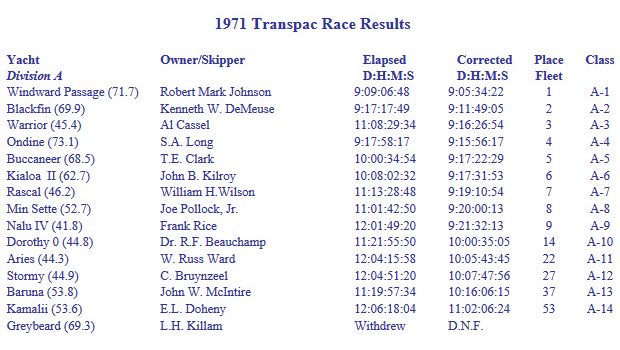

In the 1971 Transpac Race, I was crewing on the Canadian registered maxi Graybeard, owned and skippered by Lol Killian from Vancouver. It was a great race, and we were battling it out with the noted big boats of the day – Windward Passage, Kialoa, Blackfin, and Ondine.

About 500 miles out from Diamond Head, in a big squall, and of course the middle of a pitch black night, the rudder failed as the shaft had sheared at the lower bearing. After getting the sails down, a line was passed thru a hole in the top aft corner of the rudder and led through blocks to the cockpit winches. The hole was designed for this exact purpose and filled with easily removed foam. Good idea.

We got some small sails up and with four crew steering by the winches, started sailing in the general direction of Honolulu. But what we didn’t realize was that the glass and foam skeg depended on the rudder shaft for its structural strength. Bad idea.

It only lasted three or four hours before tearing off the hull, leaving a large hole and de-laminating the hull forward for about four feet, letting in lots of water, much more than the pumps could handle.

It was definitely time for a Mayday call to the escort vessel Pakeha. This happened during morning role call and Lol, cool and calm as always, apologized for not waiting his turn to be called.

Meanwhile, the crew was very motivated. A bucket brigade was formed to supplement the pumps and the aft watertight door was, with difficulty, closed (it swung the wrong way). This slowed the water intrusion to the rest of the boat, but didn’t stop it. Later we found the hollow fore and aft stringers that gave the boat her structural strength also did an excellent job of transferring the water forward.

Our first effort at repairs was to lash a storm sail over the hole. Bad idea. The jagged fiberglass immediately tore it to shreds. Next and far more effective was to stick a rolled up sleeping bag into the hole from outside. The water pressure sucked it into the hole and reduced the flow.

Still, more water was coming in than going out. Next was to try and close up the delaminated tear in the hull. By now the water level in the aft cabin with the watertight door closed was above waist height, making things difficult.

Some long poles (no idea where they came from) and various bits of wood were procured, and these were jammed between the hull and deck, forcing the split closed. It worked. We had the inflow down to a manageable level.

The Coast Guard’s closest asset was the cutter Chautauqua, on patrol at Ocean Station November, an arbitrary point in the North Pacific High where she monitored the weather and was available for any plane or ship that needed assistance. She and the race escort vessel Pakaha immediately started steaming towards us at full speed. The Coast Guard also dispatched a C130 loaded with pumps from Honolulu and the buoy tender Buttonwood to tow us in. All very welcomed and reassuring.

The first to arrive was the C130, which noted that the celestial position we gave was spot on. Over the radio they explained to us the procedure for retrieving the pumps. They would fly low and stream out 500 foot of poly-pro ski line with an ordinary household funnel as a drogue. Attached to that would be a 55 gallon drum with the pump and a parachute that had a small explosive device. This would detonate upon impact, separating the chute from the pump.

Our job was to launch a small boat, snag the poly-pro and pull in the pump. Simple right?

There were a few issues with this. Firstly, the only boat we had was an Avon dinghy with a small outboard. Secondly, the oars and floorboards were being used to shore up the aft bulkhead. Useless against the strong tradewinds anyway. The owners’ son Bunker and I volunteered. Looking back at some old photos, I realized that neither of us had a lifejacket. Things were different in those days.

The C130 would fly really slow and low directly over us from leeward and try to lay the float line close to us. This they did extremely well. Picking it up was easy but the dinghy would not tow the barrel. Getting it onboard and back to Graybeard, not so easy.

That day they dropped four pumps. On one the chute didn’t open and we never saw it. On another the release didn’t work and we watched it disappear over the horizon. Early the next day they returned with more pumps and fuel.

The Chautauqua arrived and tried to fabricate a jury rudder from 1″ pipe and boiler plate. They didn’t understand the loads involved and it bent before being used. On one trip the bosun asked Lol if we needed anything else and he jokingly said that some ice cream would be nice. A gallon of ice cream arrived on the next trip.

The Chautauqua stood by us until the Buttonwood arrived and towed us into Honolulu. Lol requested that we be towed across the finish line at Diamond Head. He logged the time and filled in the skipper’s declaration, noting “under tow for the last 500 miles”.

After docking, Lol visited the Coast Guard Commandant to thank him and asked how much was owed. The reply was, “5 bucks for the ice cream.” The Canadian/American mutual assistance agreement at its best.

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.