A smash in the face

Published on August 12th, 2023

by Gordon Baird

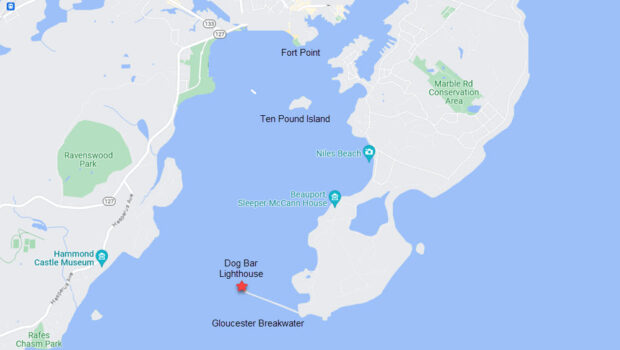

The strangest thing in being hit by a squall is in the very first moments. It’s a blind side hit, completely without warning if you are in the blackness of outside the Gloucester Breakwater (MA) as it was on a recent night.

In the faltering light, it might have telegraphed bearing down on the boat like a runaway freight train. But in the pitch black of the fog, rain and all-encompassing night, the squall hammered our Tripp 37 Crazy Uncle, returning from a long-distance race, like a speeding car running a red light – from the blind side. At least a car or a train has a light on the front.

That first moment, it struck with such a body blow that – even with no sails up – the boat began to tip over. The gusts treated the hull as a sail, rolling us into a dangerous tilt with everyone scrambling to the high side. Instinct told this driver to head directly into the wind to keep the pressure even on both sides. One slight deviation to either side began the rolling over effect.

We weren’t too far outside the Dog Bar, but the foaming seas of 50 mph gusts kept the boat short of the target. At our fast cruising speed, Uncle was making almost no headway. So up we went on the rpms, squinting through the driving rain just to keep moving forward as our hats flew from our heads into the darkness and the rapid, terrifying lightning flashes.

What seemed like forever got us near the blinking red beacon at the Breakwater’s end – my knuckles were white from gripping the soaking wheel. But passing it provided no protection at all. The wind was screaming from the north and any early turn towards the mooring would push us right onto the mighty rock bulwark, designed to protect from the opposite direction.

On we plowed through the rain coming now horizontal through the blackness. The wind waves were breaking over the bow. The gusts were unending, any relief not possible. How could we pick up or even see our mooring? I felt my way through the blindness of a crowded Eastern Point anchorage, more by muscle memory than vision.

Suddenly, lightning lit it and there it was! Our inflatable dinghy hobby-horsing wildly in the surf – we’re heading for it, get ready to grab the stick! But try as our beefy foredeckmen might, two attempts to reel in the pick-up mooring stick failed. They made the grab but couldn’t get the line aboard in the typhonic blasts.

Shooting for the mooring had turned us off the wind and we began to roll over again as in the first moments of the gale. At one point, Uncle was forced across the line between the mooring ball and the dinghy, a recipe for disaster as we were now turned at a right angle across the wind, just as at the storm’s beginning. But full-throttle reverse pulled us off the line just as the next knockdown hit and we were able to come back head to the gale to stay stable.

Crazy Uncle had been through Hell’s Half Hour by this point but, strangely, it had been too scary to be scared. More like being in a foxhole, fighting for your life. Fending off incoming attacks and shooting back with what you had. My now hoarse voice told the crew that we couldn’t try again and had to get out of there – hitting another parked boat would be deadly.

But where could we go? Not back around the Breakwater but could we make it dead on into the maelstrom to make it to Gloucester harbor? It was the only option. We would need almost full throttle to make any headway and my jilted mind kept spooking me with thoughts of running out of fuel or simply quitting after 11 hours of transiting home, motor-sailing.

A failure would have simply launched us back into the roiling, now heaving black ocean, looking more and more like death sentence. “Get that radio ready onto channel 16 in case the engine quits to call a MayDay!”

Thankfully, the reliable 35-year-old 37-foot cruiser shouldered the new responsibility like a Gloucester fireman trapped in a blaze, shrugged once and powered forward out of the danger and lurched up towards the lights of the city blinking through the streaming fog and wind. Not much was visible but the lighthouse on Ten Pound Island pierced the darkness with its red flashing light, our new hope and target.

Halfway up the outer harbor, the winds redoubled and we parked, making no headway at all. What else could we do? We had to wait it out. Uncle angled over to get more in the lee of Ten Pound and that made the difference.

Up we crept again until just under the island (luckily it was high tide), angled back into the channel and at that moment the gust took a slight pause. Long enough to get by the island and closer to The Fort where we felt some new protection from the squall. Enough to power round the corner and under the lee of the Gloucester hills.

As we approached the harbormaster’s dock, there they were, waving us in: the team from the harbormaster, out working in the storm. They were waiting to help a cruiser who had dragged his anchor in the inner harbor and run up on a lobsterman’s dock. Imagine, he dragged under the lee of the protected harbor – so picture how desperate it had been out of that breakwater.

But now we were tied to the dock. Think all that practice paid off. Needed every bit of it.

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.