R2AK: When a plan comes together

Published on June 20th, 2022

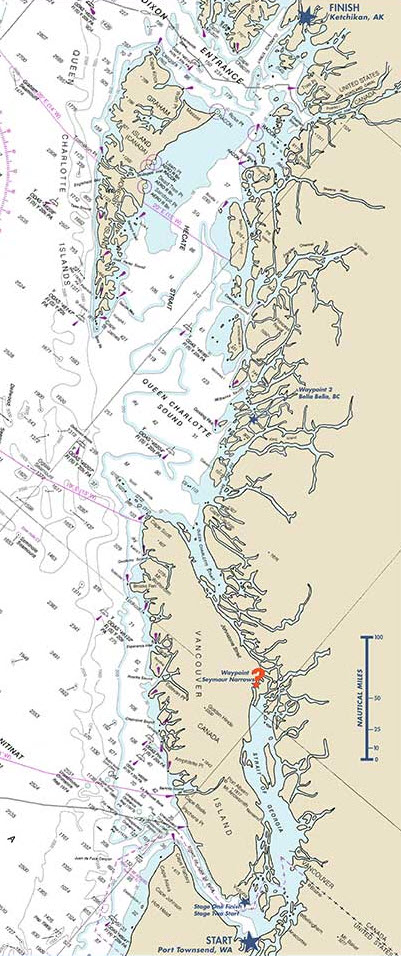

After the race was cancelled in 2020 and 2021, the 6th edition of the 750 mile Race to Alaska (R2AK) began June 13 with a 40-mile “proving stage” from Port Townsend, WA to Victoria, BC. For those that survived, they started the remaining 710 miles on June 16 to Ketchikan, AK. Here’s the day five report:

It’s been years since Ketchikan welcomed R2AK’s finishers to its shores, but by the early hour of Team Pure and Wild’s crossing of Dixon Entrance, you could tell that things were happening in welcomed and familiar ways.

As their tracker blip went from “When will they get here?” to “We better hurry!” fans clad in R2AK swag migrated from disparate corners of the community to a slow-forming flash mob that converged on the docks of the Alaska Fish House to wait for R2AK’s first finishers.

In truth, the preparations started weeks before. Volunteers made a new stand and polished the bell, the local newspaper had been peppering the headlines with updates, fishing guides volunteered to take the various cameras from R2AK and local TV to catch the team’s final approach, cash and firewood were placed on standby. It had been years, people were ready.

This was true in the five previous R2AKs, but this year’s vibe had a pent up, “Yay, and thank god” energy. There has always been a cheering mass on the dock, and the stalwart fans from Ketchikan were joined by others who had been similarly inspired. Staff of nearby restaurants ignored customers for a few minutes to cheer in the winners.

A couple made the trip down from Anchorage, another up from Texas, and at least a few from Port Townsend to be part of the celebration. Class acts to the end, Team Pocket Rockanauts might have exited the race early but made it to Ketchikan to be part of the action, and a passenger on a nearby cruise ship joined the crowd just to see what was happening.

She arrived uninformed, but Joy from Salt Lake left as the race’s newest fan and tracker enthusiast. Took pictures with the team and everything. The mood was the good kind of contagious, and if you believe the woowoo that good energy can manifest in the natural world, for at least four hours it didn’t rain. Yes, in Ketchikan.

After a run under sunny skies, Team Pure and Wild’s Riptide 44 monohull, sailed by Jonathan McKee, Matt Pistay, and Alyosha Strum-Palerm, was welcomed with cheers and applause—4 days, 4 hours, and 32 minutes after they left Victoria. As they say in these parts: Welcome to done.

It’s in the numbers:

• 36 – Minutes Team Pure and Wild missed getting the R2AK World Record for fastest monohull (2019 Team Angry Beaver – Skiff Sailing Foundation – 4d 3h 56m)

• 1 – Number of people who have taken first place in multiple R2AKs (Matt Pistay 2019, 2022)

• 183.3 – Highest mileage of any team so far in a 24-hour period (Team Pure and Wild)

They rang the bell and drank the beers, kissed their loved ones, and offered thanks. There were cameras and microphones (so many cameras and microphones), questions and stories, and crowd-wide curiosity about what had happened in the last 750 miles. In the KTN and across the global Tracker Nation, fans chimed in to share in the joy and were eager to learn how they did it.

Finish lines are the natural habitat of platitudes, and the team’s warm collected remarks on a rare rain-less day seemed to reinforce a dreamy state of topline perfection. Regardless of when racers finish (or not), Race to Alaska is often defined by a profanity-laden freight train of hardship and grit, of overcoming the sum total of logs, calms, and gales between start and finish.

If one were to simply look at Team Pure and Wild’s abstract and believe the first offered version of their elation-fueled stories, it could feel suspiciously picket fenced and perfect. Olympic and otherwise accomplished sailors, on a fast, custom, and proven vessel that finished not just first but more than a timezone ahead of the nearest competitor, all culminating in a downwind, down current, sleigh ride in the sun that ended in $10,000 and their sweeties waiting on the dock.

It all seemed too perfect.

On the surface, to habitual rock throwers and the “It’s not fair for the little guys” set, it looked like this episode of the R2AK was less of a Man-vs-Monster, late-night horror show of human struggle against impossible odds, but an after-school special where things were okay, then ended up even better.

Where was the suffering, the agony, the exhaustion? Where was the rain-soaked 2 am finish where haggard, limp drysuits stagger off their boat in a pile of walking exhaustion and struggle to muster that last crumb of sleepless adrenaline just to ring the bell before crawling into a wet bed one last time because they were too tired to move?

Some people watch NASCAR for the chance of a crash, and as thousands of fans as far away as Australia reveled in TPW’s accomplishment, to those who judge worth by proximity to failure, this all seemed suspiciously easy.

To the delight of race fans, our underwriters, and the US Coast Guard alike, Team Pure and Wild’s race wasn’t a journey to their ragged edge, but a honed demonstration of what’s possible for the incredibly capable.

However, it wasn’t all teacakes and daisies. Were there hairy moments? Totally, but they were met and dealt with. From pounding into big seas for the length of Vancouver Island, a sketchy full send shimmy out the bowsprit to retrieve a wayward tackline, the log strike in Hecate, to shredding their spinnaker as they took it down on the final night—there were plenty of occasions to rise to.

Remember, the revised course for 2022 allowed teams to choose how to pass Vancouver Island. Leave it on the port as in the past, or enter the teeth of evil with it on the starboard side. In their best rendition of ‘No guts, No Glory’, the winners went for the unknown.

One night it was so rough and uncomfortable that at least one of them got seasick despite his many ocean miles. “I ate a Dramamine then immediately puked.” The difference between these and the same-themed stories from teams who make it to Ketchikan by the skin of their teeth is that these moments of challenge weren’t survived, they were executed.

Were they tired? Sure. Their crew had been sleeping three hours out of every nine since the race began. Three hours to sleep, three at the helm, and remaining three to make food, help out on deck, and other household chores.

By our estimation, as much as their experience manifested in their ability to sail fast and safely (and they 100% did), Team Pure and Wild had two secret weapons: real food and ballast.

It seems subtle, but the ability to have relative comfort has an underrated importance in a race as long as this. You can grit your teeth for a couple days of sleeping in a wet drysuit, but finding relative comfort helps you recharge, keeps up morale, and as we know from watching Team Fashionably Late: happy crews sail faster.

Rather than the standard, boat weight conscious, racer menu of Jetboiled bags of meal-flavored rehydrated calories, Team P&W decided to spend the weight they saved by only packing one shared sleeping bag, with pre-making enough real food to last them the trip.

Yes, it was a four item menu that fell somewhere between “fourth grade birthday” and “frat house,” but the pizza, lasagna, chili, and chicken fingers that they ate for breakfast, lunch, and dinner had the calories, sustaining comfort, and practical application to keep them going.

“After the third time in the oven, the top layer of the lasagna got pretty burnt, so we’d just peel it off and have at it.”

We can only speculate, but given TPW’s new-found glory our guess is that “Lasagna: it’s not just for breakfast anymore” and “Lasagna: the food with a disposable top” are front runners for the Lasagna Council’s next ad campaign.

Also, did you catch that? The boat has an oven. They could have made cookies.

Secret weapon #2: ballast. Enabled by R2AK’s Wild West rules, the team’s ability to move weight from low side to high side played a huge role in their performance. Their Riptide 44 (aka Dark Star) already had built-in water ballast; port and starboard tanks that allow you to fill the windward tank with water to counterbalance the force of the wind and keep the boat flatter and faster.

Short course race boats use meat ballast: humans who clamber side to side between tacks, using their girth to do the same thing as the tanks. TPW’s water ballast system works like this: just before you tack, you use gravity to drain the water from the high side to the low side, then tack over. Low side with all the water on it becomes the newly weighted high side, and Bob’s your uncle.

But what about right before you tack when the water is downhill and exactly where you don’t want the weight? “It’s a little sketchy,” but the water ballast system allowed them to drive big boat performance with a shorthanded crew.

Adding to the effect, they also re-stacked their gear. Each time they tacked, one person would drive, one person would winch, and one person would re-stack and retie hundreds of pounds of sails and gear stowed both on deck and down below. They rotated the task depending on who had energy and who needed to get warm.

“It was a lot of work, you got pretty sweaty.” Especially re-stacking their sails, which were stowed on deck; moving them to the high side meant you had to start in the elements on the wet and pounding low side.

How much did all of that weight shifting matter? Their guess is they gained at least a knot, maybe two—a speed increase of 10–20%. “One of the reasons I love this race is that it allows us to sail the boat to its potential rather than to a set of rules.”

The talk around the dinner table ping-ponged from laughter-filled recollections to the technical debrief of what sails they used and when, to a deep reverence for the experience they just shared and the coastline they just experienced.

The sound of whales blowing less than half a mile off in the dead calm near Bella Bella, the pitch black transit around Cape Scott whose only light was the glowing phosphorescence of their bow wake and the outline of a fish swimming alongside for a length of time somewhere between amazing and disturbing.

“I stared at it for five minutes before I had the nerve to ask Alyosha if he could see it too. I thought I was going crazy.”

More than their experience and the race itself, talk soon turned to wondering about their fellow racers still on the course. All of the damage from logs, how much they learned about paddlewheels from Team Stern Wheelin’, and where was Zen Dog?

While they were proud of pioneering the outside route around Vancouver Island, their excitement was genuine as they learned that their “sistership,” Team Dark Star (the same-named boat of a vastly different design), was pioneering another by deviating from the standard inside route through Seymour to an even inside-er one. In a matter of hours, the winners had gone from competitors to race fans glued to the tracker.

Champions of spirit and of deed, Team Pure and Wild is sailing to raise awareness and funds for SeaShare, a non-profit that works with the fishing industry to get seafood’s high-quality protein into food banks and other food assistance programs. Pretty cool.

Our hats are off to the champions of Team Pure and Wild, and with the winner in, the race is just getting started. While there’s been 25% attrition, 26 teams are still fighting to Ketchikan. Race on!

Race details – Tracker – Facebook – Instagram

Race to Alaska, now in its 6th year, follows the same general rules which launched this madness in 2015. No motor, no support, through wild frontier, navigating by sail or peddle/paddle (but at some point both) the 750 cold water miles from Port Townsend, Washington to Ketchikan, Alaska.

Race to Alaska, now in its 6th year, follows the same general rules which launched this madness in 2015. No motor, no support, through wild frontier, navigating by sail or peddle/paddle (but at some point both) the 750 cold water miles from Port Townsend, Washington to Ketchikan, Alaska.

To save people from themselves, and possibly fulfill event insurance coverage requirements, the distance is divided into two stages. Anyone that completes the 40-mile crossing from Port Townsend to Victoria, BC can pass Go and proceed. Those that fail Stage 1 go to R2AK Jail. Their race is done. Here is the 2022 plan:

Stage 1 Race start: June 13 – Port Townsend, Washington

Stage 2 Race start: June 16 – Victoria, BC

There is $10,000 if you finish first, a set of steak knives if you’re second. Cathartic elation if you can simply complete the course. R2AK is a self-supported race with no supply drops and no safety net. Any boat without an engine can enter.

In 2019, there were 48 starters for Stage 1 and 37 finishers. Of those finishers, 35 took on Stage 2 of which 10 were tagged as DNF. There were no races in 2020 and 2021 due to the pandemic.

Source: R2AK

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.