The Environmental Conundrum

Published on October 10th, 2017

The drive for improvement, alongside that drive for convenience, has made strides for man in the short term but will be the bane of the planet long after he is gone. Adrian Morgan reports on how progress might not be.

One of the better reasons for considering a wooden boat is that they don’t last forever. Nothing, you can argue, lasts forever of course and it is a source of some anguish to me that inanimate and ecologically dodgy stuff such as the plastic spoon I just used will be floating around, possibly ground up into lethal little bits, long after I have popped my clogs.

What does a Fairy Liquid bottle bring to the world in culture and brilliance I ask you? OK, brilliance. Yet it still seems, well downright unfair. Are we humans not worth more than a plastic bottle that we should have a lifespan measured in years rather than centuries? For goodness sake; this very keyboard will outlast me, albeit buried under a tonne of landfill. It is, quite frankly, iniquitous.

Then again it is simply because we degrade, deteriorate and finally fall apart that is perhaps our greatest achievement in life: the ability to leave not a trace behind other than the stardust from which we, allegedly, were made millennia upon millennia ago.

It makes us humans special. We understand our limitations, our mortality. It should be a source of pride that gives us moral superiority over a Starbucks coffee cup or a Coke bottle or, and here we get to the rub: a glassfibre boat.

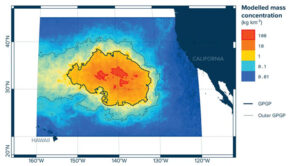

I gather there are 13,000 what they call “end-of-life” boats lying around Holland and there may well be 75,000 clogging the banks of the Ijsselmeer by 2030, unless something is done. France has made a start: 500 boats were recycled last year. Some start and yet a backlog of 15 years.

Meanwhile our old wooden boats are happily ending their own lives without any help from crushers or dismantlers by crumbling into dust, falling apart, rotting, collapsing and reverting to nature quite on their own. Even as I speak, I can hear the gribble at work. And there is, contrary to myth, no such thing as a polyester mite.

So no point in trying to recycle a 1923 cruising ketch beyond economical repair, aside from salvaging the bronze bits to use again on another wooden boat that will keep the cycle (and skills) going. Build afresh, and by all means play semantic games about “recreating the essence of the original” by way of a shard from the backbone, or even encapsulating the old shape so as to “enclose its spirit.”

Just let’s be thankful that some things are not built to last, and when they do go leave no stain (apart perhaps from the gallons of Cuprinol wood protectant that the owner before last who lived aboard on the Essex marshes poured into her bilges).

Did you know that only a handful of burials occur at sea these days in the UK, and that there are designated areas – notably off The Needles on the Isle of Wight where you are permitted to commit your naval officer father or favourite uncle to the deep, and even then rules stipulate a 440lb weight has to be attached to the coffin which has to be of soft wood and with fifty 2inch holes as well. They leave nothing to chance.

That a lengthy voyage, which explains why it is so rare. By the time the funeral party, aunts, uncles, wives, mistresses have spent five hours on the deck of a mackerel bait-stinking local sea angling boat, they will be glad to commit themselves to the deep, let alone granddad.

Cremation is another matter (just do it downwind). And don’t varnish the cockpit an hour before you set out, something which did happen – albeit it was wet epoxy, not varnish – to the late Robb White, Georgia boatbuilder when he scattered a friend’s ashes from a brand new canoe he had finished not an hour before the ceremony. Messy.

This ability of our wooden boats to depart gracefully gives us yet another reason to claim some moral superiority over those folk who buy glassfibre boats. I am not decrying glassfibre boats; quite the opposite. It is because they are so good, so perfect, so easy to maintain, and almost impossible to destroy that makes them so, well, bad?

And until we can find a way to recycle more of them into sinks (being done) at a rate that will keep up with the rate at which they are dumped, then we will by 2030 or before have a real problem.

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.