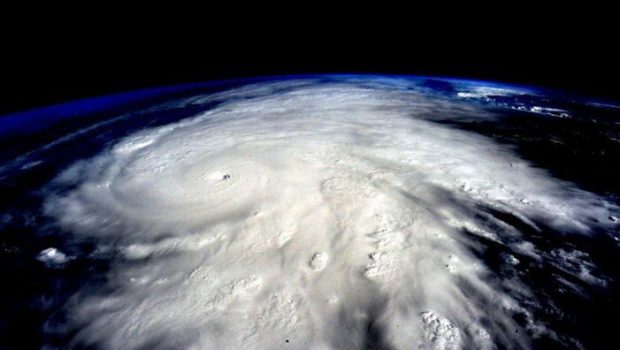

The Future of Hurricanes

Published on July 8th, 2018

As a ferocious hurricane bears down on South Florida, water managers desperately lower canals in anticipation of 4 feet of rain.

Everyone east of Dixie Highway is ordered evacuated, for fear of a menacing storm surge. Forecasters debate whether the storm will generate the 200 mph winds to achieve Category 6 status.

This is one scenario for hurricanes in a warmer world, a subject of fiendish complexity and considerable scientific research, as experts try to tease out the effects of climate change from the influences of natural climate cycles.

Some changes — such as the slowing of hurricanes’ forward motion and the worsening of storm surges from rising sea levels — are happening now. Other impacts, such as their increase in strength, may have already begun but are difficult to detect, considering all of the other climate forces at work.

But more certainty has developed over the last few years. Among the conclusions: Hurricanes will be wetter. They are likely to move slower, lingering over whatever area they hit. And although there is debate over whether there will be more or fewer of them, most researchers think hurricanes will be stronger.

“There’s almost unanimous agreement that hurricanes will produce more rain in a warmer climate,” said Adam Sobel, professor of applied physics at Columbia University and director of its Initiative on Extreme Weather and Climate.

“There’s agreement there will be increased coastal flood risk, at a minimum because of sea level rise. Most people believe that hurricanes will get, on average, stronger. There’s more debate about whether we can detect that already.”

No one knows how strong they could get, as they’re fueled by warmer ocean water. Timothy Hall, senior scientist at the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, said top wind speeds of up to 230 mph could occur by the end of the century, if current global warming trends continue.

This would be the strength of an F-4 tornado, which can pick up cars and throw them through the air (although tornadoes, because of their rapid changes of wind direction, are considered more destructive).

Does that mean the five-category hurricane scale should be expanded to include a Category 6, or even Category 7?

The Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale, developed in the early 1970s, ranks hurricanes from Category 1, which means winds of 74-95 mph, to Category 5, which covers winds of 157 mph or more.

Since each category covers a range of wind speeds, it would appear that once wind speed reaches 190 or 200 mph, the pattern may call for another category. Last season saw two Category 5 hurricanes, Irma and Maria, with Irma reaching 180 mph. And in 2015, off Mexico’s Pacific coast, Hurricane Patricia achieved a freakish sustained wind speed of 215 mph.

“If we had twice as many Category 5s — at some point, several decades down the line — if that seems to be the new norm, then yes, we’d want to have more partitioning at the upper part of the scale,” Hall said. “At that point, a Category 6 would be a reasonable thing to do.’’

Many scientists and forecasters aren’t particularly interested in categories anyway, since these capture only wind speed and not the other dangers posed by hurricanes.

“We’ve tried to steer the focus toward the individual hazards, which include storm surge, wind, rainfall, tornadoes and rip currents, instead of the particular category of the storm, which only provides information about the hazard from wind,” said Dennis Feltgen, spokesman for the National Hurricane Center.

“Category 5 on the Saffir-Simpson scale already captures ‘catastrophic damage’ from wind, so it’s not clear that there would be a need for another category even if storms were to get stronger.”

Among the most solid predictions is that storms will move more slowly. In fact, this has already happened. A new study in the journal Nature found that tropical cyclones have decreased their forward speed by 10% since 1949, and many scientists expect this trend to continue.

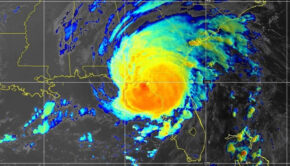

This doesn’t mean a hurricane’s winds would slow down. It means the hurricane would be more likely to linger over an area — like last year’s Hurricane Harvey. It settled over the Houston area and dropped more than 4 feet of rain on some areas, flooding thousands of houses.

In addition to moving slower, future hurricanes are expected to dump a lot more rain. A study by scientists at the National Center for Atmospheric Research this year looked at how 20 Atlantic hurricanes would change if they took place at the end of the century, under the average projection for global warming.

Warm air holds more water than cold air — which is why no one complains about the humidity when it’s cold out. The study found hurricanes would generate an average of 24% more rain, an increase that guarantees more storms would produce catastrophic flooding.

The production of horrifying amounts of rain shows another way in which Harvey is a window into the future. One study, which looked at how much rain Harvey would have produced if it had formed in the 1950s, found that global warming had increased its rainfall by up to 38%.

Other scientists see Harvey less as a symptom of climate change than an indication of what we can expect in the future.

“Whether we’re talking about a change in the number of storms or an increase in the most intense storms, the changes that are likely to come from global warming are not likely to be detectable until 50 years from now,” said Brian Soden, professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science.

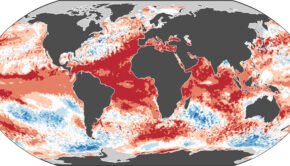

Warm ocean water provides the fuel for hurricanes, but a hotter world would not necessarily produce more of them. While many scientists for a long time did think an increase in temperatures would produce more storms, they have begun focusing on factors that could suppress the formation of hurricanes.

Many models for future climates show an increase in wind shear, the crisscrossing high-altitude winds that tear up incipient tropical cyclones. And they show less of the atmospheric instability necessary for the generation of thunderstorms.

But now the thinking is swinging back.

“We used to think 20 years ago that in a warmer climate there would be more hurricanes,” said Sobel, of Columbia. “Then the computer models got better. Most of those started to show fewer hurricanes, not more. No one knew why. Then some of the models started to show increases with warming. So I think we’re back to where we don’t know.”

Source: Los Angeles Times

Note: Beryl became the Atlantic storm season’s first hurricane on July 6 but has since lost strength as it moves west-northwest on a track across the Lesser Antilles island chain on July 8 and near or south of the Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico on July 9.

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.