R2AK: When pretty good is really good

Published on June 15th, 2019

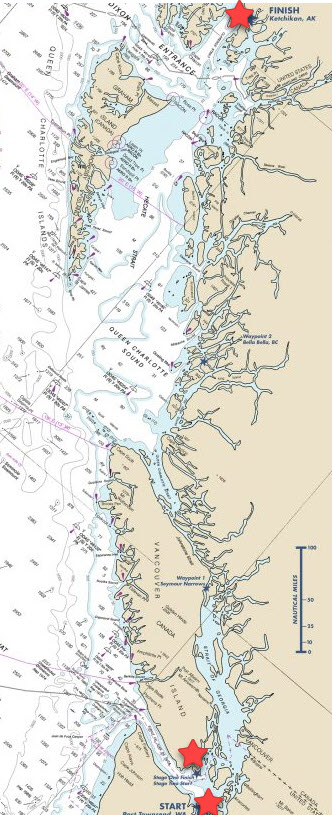

The 5th edition of the 750 mile Race to Alaska began June 3 with a 40-mile “proving stage” from Port Townsend, WA to Victoria, BC. For those that survived, they started the remaining 710 miles on June 6 to Ketchikan, AK. Here’s the June 15 update:

With its lack of handicaps, lack of rules, and Wild West attitude, on the surface it would seem the Race to Alaska is a setup to disappoint just about everyone. If you’re focused only on the capital “W” win, it’s a forgone conclusion that bankrolled teams of sailors with better-than-Olympics credentials will grab the prize, grab the glory, and leave the everyone else in the dust.

To the surprise of no one close to the race and paying attention, that preconception is as true as it isn’t. While the only prizes were given out some five days prior, recognition of the valor and dedication of those who simply finish could be seen at the dock today as throngs of teams who came before were on hand to welcome finishers.

Sometimes it’s about standing on the podium, but most of the time it’s about standing with yourself and the satisfaction you’ve done something extraordinary—whether or not people applaud. The two teams bookending today’s Ketchikan finish line embody the second kind of accomplishment and seemingly represent a time-lapsed view of Canadian lives well-sailed.

Hitting the dock on the AM side of the clock was Team Pitoraq, whose hard fought, non-stop was the culmination of a lifetime progression towards the ultimate.

Pitoraq’s Wayward 30 has been in the family since it sprang to life, from idea to actual vessel, in the same hands that brought it across the finish line. It’s not the only boat their skipper had ever sailed, but it’s the only one he’s had since he built it 30-plus years ago.

Race to Alaska was something he followed for years, then finally entered on the condition they would race, not to win, but to push the boat and crew to the full extent of their collective abilities. If a micro-stat victory was needed, they could hang their hat on being the first team to complete the course that missed the first tide at Seymour Narrows.

Depending on the crewmember telling the stories, their victory was a deliberative result of a lifetime of incremental, or the result of epiphany moments that longed for a life better lived. The skipper had built the Wayward 30 for their collective progression through local, and then far-ranging adventure.

The crew’s narrative included a realization that the life worth living looked a little more like salt water and less like the urban decadence of a ladder-climbing job and keeping up with the theoretical Joneses. The paths of captain and crew merged during R2AK and they spent eight days watch-on-watch sailing 24/7 until they rang the bell in Ketchikan.

They finished tired. The boat had proven as solid as their preparations, and while by their own accounts their campaign had run them to the end of their reserves, other than breaking an oar and several pairs of reading glasses, the toll of a race run non-stop was evident only in their tired faces. This had been the epic they were looking for.

After the race for first is decided, R2AK teams find their own competitors, and Team Pitoraq’s was Team MBR. “We could see the McGuffins in the day with the binoculars, but at night we’d lose them. We were always worried that they’d snuck in front of us. It’s a race, eh?”

Pitoraq never stopped sailing, never stopped striving, and while they were dog tired when they hit the dock, they never stopped being a class act. They addressed the KYC commodore with what we’re guessing was the first “Madame” she’d had in a while. Salmon, tourists, camaraderie, and community; Ketchikan draws a strong suit on a lot of things—formality they tend to leave to other people.

By the time Pitoraq’s first nap was one-burger behind them, the Teen Beat sleeper cell sensation of Team McGuffin Brothers Racing completed the course and earned the honor of being the collectively youngest team to ever finish this thing. If only to revel in the incredible in a way they probably won’t, we’d like to point out that the new bar for youngest team boasts an average age of 19.25 years.

If Team Pitoraq’s victory was rooted in a lifetime culmination, Team MBR’s landed solidly in the “Are you kidding me?” envy of a teenage rite of passage, with everyone greeting them on the dock in Ketchikan wishing they’d had the parents and the courage to have done this in their day.

Sailing a J/24, the cherub-cheeked, aw shucks everything of the three actual and one honorary brothers won the day and the, hearts of fellow racers and Ketchikan fans who came down to welcome them. To a person, the onlookers were in awe of a life path so well started and largely yet to come. “This trip is something that the rest of us built towards, this is their baseline—imagine what else they’ll do.”

The crowd was as impressed as it was filled with questions, and the brothers deferential answers were those of the humble, their sparse words offered in the rare brand of taciturn that lies between shy and polite, and rattles to a stop at nothing less than a sincerely optimistic “Pretty good” that is ubiquitously accompanied by a full body nod that starts at the toes; like they’re channelling an agreeable species of sea horse. They hit the dock with uniformly bare feet and matching grey sweaters with MBR patches hand sewn on the breast.

How did you pick your uniforms?

“Well, I like Stanfields, and Callum likes Stanfields so we thought they would be pretty good.”

How was the boat?

“Pretty good.” They had leaks from the forward hatch, main hatch, lazarette hatch, the toe rail, and the mast boot. “Pretty much everything leaked.” The only time they begrudgingly conceded things might have been less than ideal were the times when they woke up for watch in the 1am darkness and waded through the damp clothes they had drying below. “There was a big wave, and we had our hatch open, and we got pretty wet. I broke the leeboard and ended up in Duncan’s bunk, but other than that, it was pretty good.”

What did you eat?

“Baked beans, chia pudding, and canned sprats.” Sprats, for the un-indoctrinated are the tins of fish that they would crack open and share for lunch, dinner and sometimes breakfast. Three times a day and for eight days straight; unabashed, unresentful and recounted with a smile. The tins were the gift of their grandfather in Ottawa who bought them and sent them; apparently making the rounds and clearing the shelves of Ottawa’s strategic reserve of tinned fish to send his boys north. The fact that they were eating canned fish bought in Canada’s inland capital 3,000 kilometers east, then sent to the heart of it’s seafood industry was an irony that only occurred to them after the question was posed. They had food, they ate it gratefully, and had enough leftover that they were planning on eating it for their return trip south. Sprats north, sprats south, and on the way back they were going to meet up with their grandfather, Grandad Sprats himself. There’d be plenty for him too.

What did you miss?

“None of us drink coffee or beer, so we’re set on those.” They settled on hamburgers, and after climbing the dock to the racer party they set into a four identical plates of burgers and fries, appreciatively consumed at a politely moderate pace.

What do they do for fun?

“Well, we mostly just sail.” They replied to the question of whether or not it felt weird to be done, with the unintentional punchline: “Well, we still have to go all the way back…”

They were planning on shore leave of no more than a day. They needed to get back, so were going to limit their wild and crazy to picking up their outboard, restocking some fresh food, and that’s exactly it. Duncan was hoping to make it back in time for his last day of school, the rest were going to get ready for their canoe trip down the MacKenzie river.

For the teams that came before, and likely those to come, the finish line is at least a reprieve and at most an ending. For Team MBR it was the beginning of a no-parents summer that starts with R2AK and culminates in a canoe trip to the Arctic circle.

The trip to K-town wasn’t a hardship, it was fun; not the vice fueled Spring Break binge of excess of their peers to the south, it was the adventure version of a jigsaw puzzle and a cup-of-tea type enjoyable. So was the trip back that couldn’t start soon enough. They had their grandad’s sprats, the last thing they needed was to hang around on shore and stress consume in order to cope with a hardship that for them doesn’t even exist. They are the very definition of “Pretty good.”

Whether you are more or less than their average of 19 years, imagine where you would be after eight days and 700 miles of non-stop sailing.

Would you gloat in self-satisfaction? Would you crave the indulgences of civilization, movies, girls, or at the very least a temporary antidote to the banal inconveniences that brought you here: a dry bed, a hot shower, a plated meal, ice cream—anything other than the steady state diet of less sleep and more canned fish? Would you offer a tinge of anything less that the honest and holisitic optimism of “Pretty good”?

For the McGuffins, and to the envy of everyone, their answer was true. They were pretty good, and their smiles were only rivaled by those on the adults at the dock who had found in them the role models for youth they were too late to follow.

They had just sailed to Alaska, alone and unassisted as young as 16 and with as little as six months sailing experience. They weren’t self-impressed or particularly jubilant, and it didn’t seem to dawn on them to be as proud as everyone else was. They were “pretty good,” but better than just about everybody.

Race details – Team list – Tracker – Results – Facebook – Instagram

For the second year in a row, a monohull has taken line honors. Here’s the history:

2015 – 5 days 1 hour 55 min – Elsie Piddock

2016 – 3 days 20 hour 13 minutes – Mad Dog

2017 – 4 days 3 hour 5 minutes – Freeburd

2018 – 6 days 13 hour 17 minutes – First Federal’s Sail Like a Girl

2019 – 4 days 3 hours 56 minutes – Angry Beaver – Sailing Skiff Foundation

Background:

Background:

Race to Alaska, now in its 5th year, follows the same rules which launched this madness. No motor, no support, through wild frontier, navigating by sail or peddle/paddle (but at some point both) the 750 cold water miles from Port Townsend, Washington to Ketchikan, Alaska.

To save people from themselves, and possibly fulfill event insurance coverage requirements, the distance is divided into two stages. Anyone that completes the 40-mile crossing from Port Townsend to Victoria, BC can pass Go and proceed. Those that fail Stage 1 go to R2AK Jail. Their race is done.

Stage 1 Race start: 0500 June 3rd, Port Townsend, Washington

Stage 2 Race start: 1200 June 6th, Victoria, BC

There is $10,000 if you finish first, a set of steak knives if you’re second. Cathartic elation if you can simply complete the course. R2AK is a self-supported race with no supply drops and no safety net. Any boat without an engine can enter.

Last year 37 teams were accepted and 21 finished.

Source: Race to Alaska

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.