America’s Cup: What’s old is new again

Published on December 14th, 2020

When the new class of boat for the 36th America’s Cup was revealed, there was general surprise at what the New Zealand defender had revealed. The AC75, with its side foils, was unlike anything on the water.

But regarding originality, writer Mark Twain had his doubts: “There is no such thing as a new idea. We simply take a lot of old ideas and put them into a sort of mental kaleidoscope.”

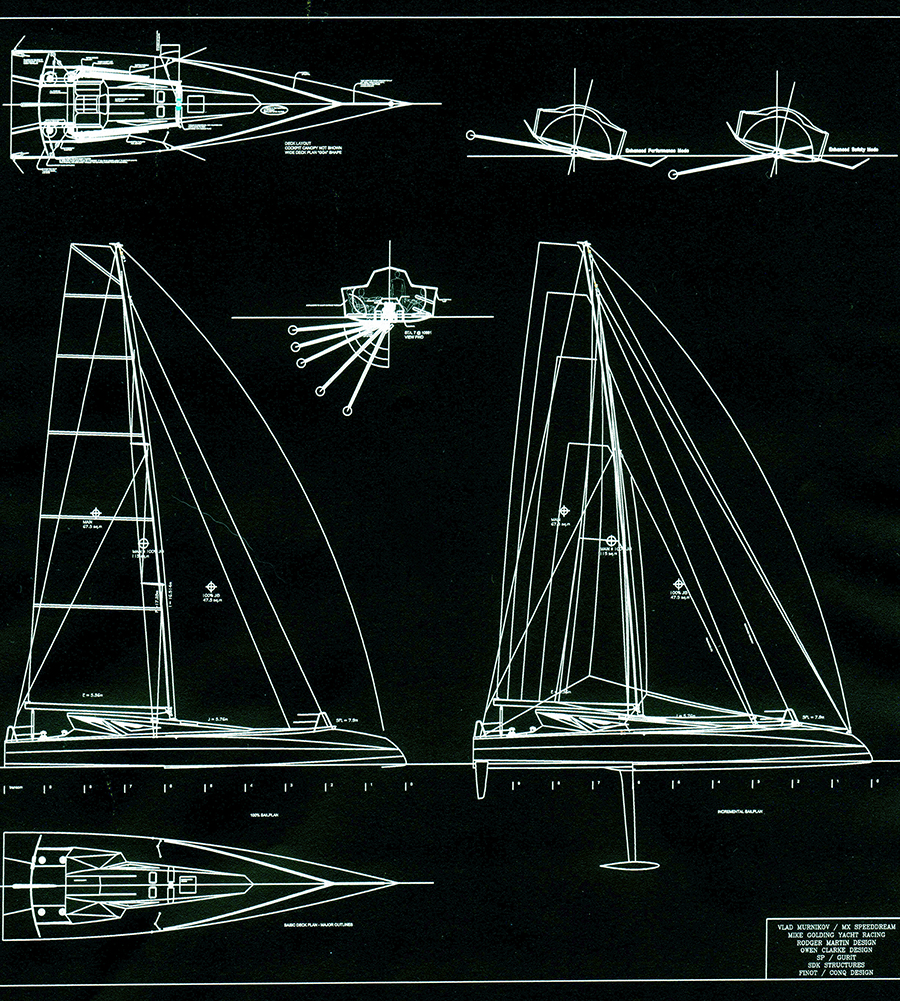

Yacht designer Vlad Murnikov may agree with that assessment as he analyzes the AC75 design through the prism of his SpeedDream concept, which is what he considers to be the original foiling monohull with flying ballast:

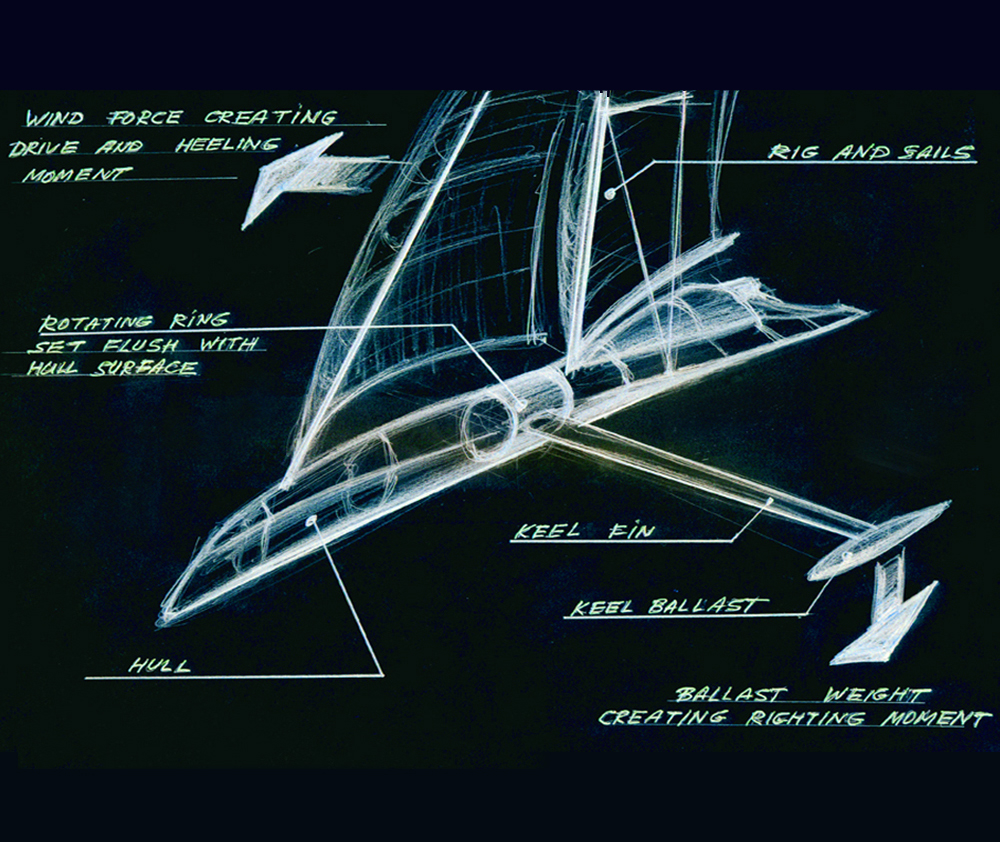

Back in 2008 SpeedDream was created as a safer alternative to catamarans and trimarans to participate in ocean racing and record round the world attempts for the Jules Verne Trophy. Multihulls have long since proven their excellent performance. They are capable of phenomenal speed, but they have serious fault – lack of ultimate stability.

Their high initial stability vanishes rapidly as the boat heels and that often leads to capsize. The consequences could be catastrophic, especially if this happens in the open ocean. And once capsized they are all but impossible to right up without outside assistance.

Traditional keelboats are much safer because ballasted monohulls have significantly lower chance of capsizing, and even if this happens, they can right themselves up. However, the ballast makes them much heavier than catamarans and trimarans, and therefore slower.

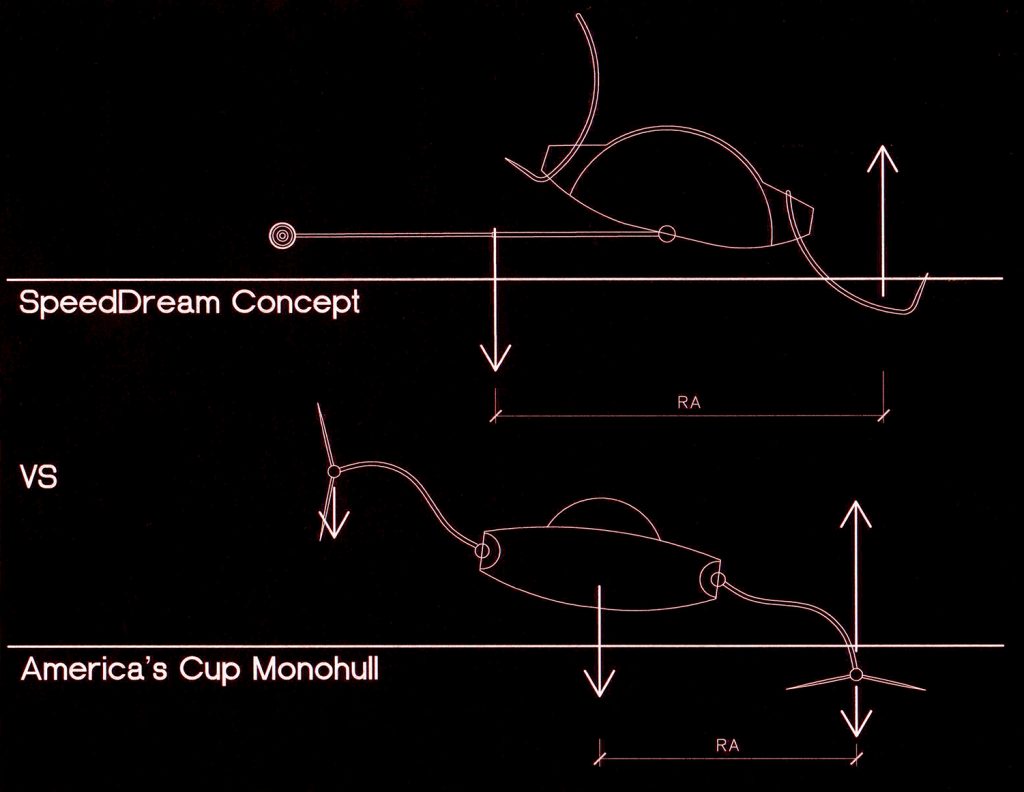

I set up a goal to create a monohull that would match speed potential of multihull, while retaining safety of keelboat. I was able to achieve this by inventing the flying keel which comes out of water while sailing and moves center of gravity as far as possible to windward. This keel works in tandem with hydrofoil that shifts lifting force far to leeward creating righting moment comparable to monohull of the same displacement.

The project was developed during 2008-2014 and went through several stages. Initial concept achieved canting angle of 80 degrees from centerline (as compared to 40 degrees for the Volvo and IMOCA boats). Gradually improving canting systems I invented the keel that could rotate around boat’s hull to any angle necessary.

Foils went through evolution as well, starting with dynamic support of about 75% of displacement and eventually coming to a foiling system allowing for full flight over water.

After securing sponsorship from Russian technology giant Yandex, we built a 27-feet proof of concept prototype to test the flying keel. On the very first outing to sea in the fall of 2012, it all worked!

Testing had continued the following summer, while simultaneously participating in various sponsorship programs for Yandex and showing the prototype in France and England during Extreme Sailing Series. Most of SpeedDream sailing that summer went in light and medium winds, and the boat speed was sailing consistently at 1.3 to 1.5 of wind speed. At that time it was a great result for a monohull, and we knew it was just the beginning!

We felt fully satisfied with the results of initial testing and began working on outfitting the prototype with hydrofoils, which we planned to try in the summer of 2014. Our sponsor Yandex too was happy with the results of the PR events when the innovative Yandex-Speeddream was demonstrated to their clients and partners, invited to be a part of various sailing events that went along with testing of the prototype.

As a result, we jointly came to an agreement to build a 50-foot SpeedDream version to participate in Route de Rum transatlantic race with Mike Golding as a skipper. Design started in the second half of 2013, and by the winter we were ready to begin construction of the boat.

Unfortunately, this coincided with the events in Ukraine, Russian annexation of Crimea, and the following US economic sanctions. In such an environment, Yandex made a decision to put the SpeedDream project on hold until better political times. Regretfully, those better times have never arrived…

Experiment in Oddity

When I first introduced the SpeedDream concept more than a decade ago, the initial reaction of the sailing community was unanimous – this could never work. The idea that a monohull could reach speed comparable to multihulls was considered a heresy. Even the world’s leading designers failed to understand and appreciate my ideas.

However, in a short couple of years, as the project developed and we built and tested the first SpeedDream prototype, the same designers began competing for a position in our expanding design team after it became known that we would be building a 50-foot boat, on the way to full scale SpeedDream 100 for Jules Verne’s Trophy.

The sudden stopping of the project was a huge disappointment. However, as the time has shown, our efforts were not in vein.

The SpeedDream ideas have gradually found their way into the latest generation of IMOCA boats as well as other high performance racing yachts. The culmination came with the America’s Cup abandoning catamarans and electing foiling monohulls with flying ballast for their 2021 Challenge.

While the overall AC75 concept has been influenced by the SpeedDream, the details of the America’s Cup interpretation and execution continue surprising me. Here I will analyze several major issues as I see it.

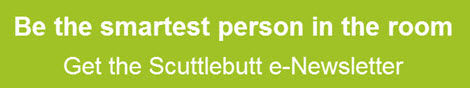

Instead of a simple and logical SpeedDream set-up where functions of the ballast and lifting force are clearly separated, and the ballast is placed to the windward and lifting foil – to leeward for the maximum efficiency, the AC 75 layout uses foils that play the role of the ballast as well.

In this configuration, ballast placed on the opposite sides of the boat adds nothing to stability, and is needed only for self-righting the yacht. Until the yacht has not capsized, it is just a dead weight – and quite a substantial one.

According to the AC rules, each foil weights 1175 kg. Part of this weight is needed to provide structural integrity. My guess is this it’s somewhere between 300-400 kg. The rest is ballast, 700-800 kg per foil, 1.5 ton total. And that’s almost a quarter of the boats’ overall displacement of 6.5 tons. Had they used the SpeedDream configuration, the boats could’ve been this much lighter and therefore faster.

I understand the logic of the AC designers and rule creators who think this way it would be easier to achieve foiling tacks and jibes. Even though during the SpeedDream project, we did not have a chance to test foils, my intuition tells me that foiling tacking and jibing could be done with a canting keel as well.

Yes, bringing the keel back into the water and moving it to the other side of a boat would slow her down and consequently lift on the foil would be reduced. However, this would be compensated by the fact that during the turn both foils would be in water, doubling the lift.

Our SpeedDream 27-foot prototype showed it was possible to move the keel from side to side in less than 10 seconds. It slowed a boat a bit, but not as much as to cause her to get down from foiling, I believe.

And then of course there is a matter of esthetics. When I first saw the presentation of the AC75 concept, I honestly felt it was a joke, or an attempt to put up a smoke screen, hiding the real idea. Let’s face it: the boat looks bizarre, resembling a giant water bug awkwardly gliding over water with one leg high up.

Additionally, while the boats look comical, they are also seriously dangerous machines with their upright swords flying at 50+ knots. Of course the organizers will impose separation zones around the boats to minimize chances of close encounters, but it would make the racing less appealing and less fun to watch, and still won’t completely eliminate the danger altogether.

By contrast, the SpeedDream was conceived as an offshore monohull to challenge for the Jules Verne Trophy. For this solitary job, a flying keel poses no danger. I was reluctant to suggest SpeedDream concept application for close round-the-buoy racing for the obvious reasons. Yet, the SpeedDream blunt bulb flying low over water surface is on one level of danger, while the AC75 boats’ vertical foils are on a totally different danger plain. They really look terrifying…

In conclusion, I would like to draw attention to one more fact about the AC75 stability – or lack thereof. These boats have only dynamic stability while foiling and form stability while sailing in displacement mode. The ballast that the boats carry has nothing to do with stability.

If at high speed in fresh breeze an AC75 boat crashes down from foiling for some reason (for example because of foil ventilation caused by rogue wave or crew error), she would most likely capsize, and even after self-righting, a long time will be required to accelerate and get back into foiling. In real racing conditions, such loss of time would most likely mean the loss of a race. Here’s an example:

Fasten Your Seatbelts

Having said all of the above, I have to admit that I nevertheless admire this new breed of yachting speed machines and cannot wait to see them performing during racing. Yes, they are not perfect, they could have been better, but even as they are, this is the very pinnacle of modern sailing.

As a concept, the SpeedDream approach is maybe more advanced and efficient, but for the main part it remains only a theoretical idea. As for these four AC75 boats, it is a reality and a huge achievement. Fairly open class rules have resulted in four distinct boats that already undergone substantial amount of development and improvements while moving from their first generation boats to the second one.

Which one is the best from a technical viewpoint? I would bet on the Kiwis. After all, they developed the class rules, and who if not they know how to better navigate them for the advantage. Even more importantly, New Zealanders are among world’s best sailors and defending the America’s Cup is a matter of national pride and importance for them. And of course the level of experience and personal achievements of the team leader Grant Dalton is matchless.

Emirates Team New Zealand and to some extend INEOS Team UK have hulls designed to achieve maximum form stability with their vertically cut sides and maximum waterline beam. This might help them prevent capsizing after crashing down from foiling. American Magic and Italian Luna Rosa opted for more elegant smooth forms with reduced surfaces that might help them to lift into foiling in lighter air but might be a problem in displacement sailing, especially in a breeze.

It is going to be very exciting racing. Let it start!

Perhaps Howard Aiken, an American physicist and a pioneer in computing, said it best when he observed, “Don’t worry about people stealing an idea. If it’s original, you will have to ram it down their throats.”

Details: www.americascup.com

36th America’s Cup

In addition to Challenges from Italy, USA, and Great Britain that were accepted during the initial entry period (January 1 to June 30, 2018), eight additional Notices of Challenge were received by the late entry deadline on November 30, 2018. Of those eight submittals, entries from Malta, USA, and the Netherlands were also accepted. Here’s the list:

Defender:

• Emirates Team New Zealand (NZL)

Challengers:

• Luna Rossa (ITA) – Challenger of Record

• American Magic (USA)

• INEOS Team UK (GBR)

• Malta Altus Challenge (MLT) – WITHDRAWN

• Stars + Stripes Team USA (USA) – WITHDRAWN

• DutchSail (NED) – WITHDRAWN

Key America’s Cup dates:

✔ September 28, 2017: 36th America’s Cup Protocol released

✔ November 30, 2017: AC75 Class concepts released to key stakeholders

✔ January 1, 2018: Entries for Challengers open

✔ March 31, 2018: AC75 Class Rule published

✔ June 30, 2018: Entries for Challengers close

✔ August 31, 2018: Location of the America’s Cup Match and The PRADA Cup confirmed

✔ August 31, 2018: Specific race course area confirmed

✔ November 30, 2018: Late entries deadline

✔ March 31, 2019: Boat 1 can be launched (DELAYED)

✔ 2nd half of 2019: 2 x America’s Cup World Series events (CANCELLED)

✔ October 1, 2019: US$1million late entry fee deadline (NOT KNOWN)

✔ February 1, 2020: Boat 2 can be launched (DELAYED)

✔ April 23-26, 2020: First (1/3) America’s Cup World Series event in Cagliari, Sardinia (CANCELLED)

✔ June 4-7, 2020: Second (2/3) America’s Cup World Series event in Portsmouth, England (CANCELLED)

• December 17-20, 2020: Third (3/3) America’s Cup World Series event in Auckland, New Zealand

• January 15-February 22, 2021: The PRADA Cup Challenger Selection Series

• March 6-15, 2021: The America’s Cup Match

Youth America’s Cup Competition (CANCELLED)

• February 18-23, 2021

• March 1-5, 2021

• March 8-12, 2021

AC75 launch dates:

September 6, 2019 – Emirates Team New Zealand (NZL), Boat 1

September 10, 2019 – American Magic (USA), Boat 1; actual launch date earlier but not released

October 2, 2019 – Luna Rossa (ITA), Boat 1

October 4, 2019 – INEOS Team UK (GBR), Boat 1

October 16, 2020 – American Magic (USA), Boat 2

October 17, 2020 – INEOS Team UK (GBR), Boat 2

October 20, 2020 – Luna Rossa (ITA), Boat 2

November 19, 2020 – Emirates Team New Zealand (NZL), Boat 2

Details: www.americascup.com

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.