Reflections on the 1979 Fastnet Race

Published on December 9th, 2013

Ned Shuman, Captain, USN (Ret), 82, passed on December 4, 2013. During his eventful life, he was Officer-in-Charge and senior coach of a crew of midshipmen during the tragic 1979 Fastnet Race which incurred 15 fatalities. Here is the report Ned submitted in April 1999…

On 11 August 1979, the U. S. Naval Academy yacht Alliance crossed the starting line off the Royal Yacht Squadron in Cowes, Isle of Wight, England, on the biannual Fastnet Race. Alliance was a 56-foot aluminum sloop. On board were Lieutenant Commander Chip Barber, civilian coach Bob Smyth, Ensign Kevin Mathison, eight midshipmen, and yours truly – the officer-in-charge.

The forecast predicted light winds. On the morning of the start, the crew thought to lighten the boat by unloading several of the heavy-weather sails. My orders to put them back aboard were met with a general lack of enthusiasm. I pointed out to the skeptics that the 605-nautical-mile Fastnet Race had a nasty reputation for rough conditions in spite of forecast weather.

The boat was strong and the crew had just won the TransAtlantic race from Marblehead, Massachusetts, to Crosshaven, Ireland, beating such well known ocean racers as Kialoa , Ondine, Condor, and Sleuth – an extraordinary achievement. They had done well in the Cowes week events including the 217-mile Channel race; they were tough, experienced, and ready. All Category One equipment was on board.

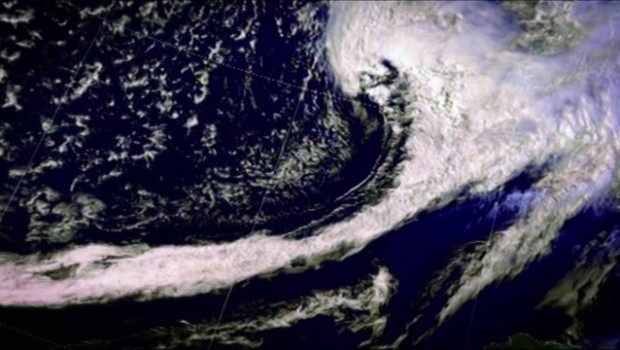

During the night of 12/13 August, Chip, our navigator, began to get reports of possible heavy weather. Nothing we couldn’t handle; we had experienced 40+ knot winds on the TransAtlantic. It didn’t take long to go from a number one jib and full main (big sails) to bare poles as the seas and wind built; shortening down, we destroyed the number three jib and had to cut it loose and throw it over the side. We were 60 miles from Fastnet Rock and getting pasted.

Finally, we were able to hoist a storm jib and storm trysail (the smallest sails). There is nothing like the sound of waves breaking over an aluminum boat to get one’s attention – and it was dark, real dark. Most of the crew was sick, but the boat was under control and holding up well. The shore was to leeward, so there was no place to run.

We became aware of a massive search-and-rescue attempt under way by both ships and helicopters, which did nothing to alleviate the already high pucker factor. Chip nailed Fastnet Rock using dead reckoning, a radio direction finder, and a fathometer. No easy job in the days before GPS; Loran C was not available, and the weather precluded celestial. As the wind eased and the seas settled, we were able to bend on more sail. We signaled a Royal Navy helicopter that we were all right and would complete the race.

When we docked at the Royal Marine Base in Plymouth, we heard the bad news: 15 fatalities, 5 boats sunk, and 24 boats abandoned. Of the 303 starters, only 85 finished. All of the fatalities occurred on boats less than 39 feet long and only one boat over 39 feet was abandoned. On the positive side, one ensign and eight midshipmen – Hampshire, Fish, Aruffo, Cheney, Donofrio, Kineke, Mortonson, and Perry – had passed a stiff test with flying colors.

I have often compared ocean racing in bad weather with being a prisoner of war, an environment with which, unfortunately, I have some experience. Harsh conditions, cramped quarters, bad food (really bad on boats stocked by midshipmen), and diverse personalities. Instead of the guards beating on you, mother nature takes over. You can’t get out so you make the best of it. It’s a character-builder.

Here we are, 20 years later, with a similar occurrence on the Sidney-Hobart race. What have we learned? First, from what I have read I think the conditions on the Sidney-Hobart were worse. Second, as a result of the 1979 Fastnet race offshore safety has made massive improvements. Equipment is superior, race management is better, crews are better prepared, and arguably, boats may be better.

What happened? Simply stated, the ocean is capable of providing more pain than man or machine can endure. All race committees require the participants to sign disclaimers that state that the skipper is responsible for his boat and that the decision to race or not to race is his alone. Does that mean that the race committee is blameless if they knowingly start a race in advance of an impending storm? I don’t think so. I am not concluding that the Sidney/Hobart race committee was negligent or responsible for the disaster. It is still being investigated. Ocean racers, aviators, skydivers, balloonists, mountain climbers, downhill ski racers, etc., are risk takers. No risk, no fun. They don’t back down or quit easily. I have long maintained that if someone sponsored a race from Newport to Bermuda in J-24s it would probably be oversubscribed.

Who can protect these risk takers from themselves? Maybe no one. Race committees have postponed major offshore races based on weather, but it is always a tough call.

The difficult question remains: How much risk and expense should the various rescue units of the world accept in rescuing the participants of these ill fated endeavors? Perhaps the panel at this month’s Naval Institute Annual Meeting can address the issue.

Captain Shuman, a naval aviator, was shot down over North Vietnam in March 1968 and spent five years as a prisoner of war. He wrote “Back to Hanoi,” published in Proceedings , October 1992, pp. 81-85.

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.