Chasing Gold and Falling Short

Published on November 30th, 2017

The Olympic Games is the highest peak in Sailing. There was a time when USA dominated but the landscape changed. The world got more focused while American youth sailing committed to less technical boats. As a result, the failure rate rose when sailors in their 20s sought to make up for lost time.

An earlier commitment to Olympic style racing is now needed during the teenage years so that when a person is able to fully focus on qualifying for the Games, they have a solid foundation to build from. Preparing for the biggest stage in sailing must start early.

In this report by Natalya Doris, she profiles the struggles two decorated college sailors faced to fulfill their Olympic dream.

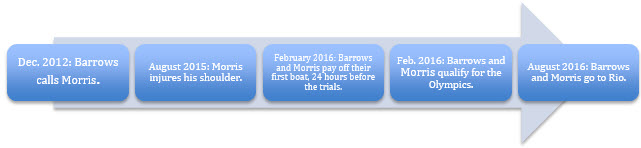

In late December 2012, Yale grad Joe Morris received a phone call from his best friend and teammate, Thomas Barrows, who graduated two years before him at Yale. Barrows was considering pursuing an Olympic campaign in the Men’s 49er skiff and was looking for a training partner.

A few days before this conversation, Morris had quit his desk job in Switzerland. He couldn’t stand the thought of staring at a computer screen for another 12 hours. His lifelong passion, sailing, involved spending at least a few hours a day on the water, and his job had kept him from that for eight months.

Even when he was at work, the Olympics weren’t far from his thoughts. In this time, Morris says he kept a list of three people with whom he would have been willing to campaign. After all, since the young age of ten years old, representing the United States at the Olympic Games was his dream.

When he got that phone call 13 years later, from the person atop his list, the answer came easily.

There began a four-year-long saga of how two best friends would “chase their tails,” as Morris puts it, earn a spot on the 2016 U.S. Olympic Sailing Team… only to place second-to-last in their fleet in Rio.

But the problem rests deeper than their result – after all, being one of the top 20 Men’s 49er teams in the world is something to be proud of – it lies in the nature of starting an Olympic campaign in the United States as an underdog.

More Than Just a Dream

After getting that phone call, Morris flew to the U.S. Virgin Islands, where Barrows grew up, and the duo began their first few months of training.

After getting that phone call, Morris flew to the U.S. Virgin Islands, where Barrows grew up, and the duo began their first few months of training.

It took time for Morris to get back into his old physical routines – he says, “I was out of shape and 49ers are very physically demanding.” But it took very little for him to realize how well they worked together.

“Pretty quickly,” he says, “we knew that we approached sailing in a similar way and that we had very complementary skills… we realized that it could be a good partnership.”

Combined, they had earned eight All-American Awards from the Inter-Collegiate Sailing Association (ICSA), regarded as the highest honor in College Sailing, two College Sailor of the Year Awards – one nationally and one in New England – and at least 11 national championships.

Finding the right person to sail with, according to Morris, is the “single most important thing [in running a two-person campaign]… outside of funding.”

Competitive sailing is much more expensive than many other sports. At a minimum it requires a boat, sails and proper sailing gear. (A brand new 49er costs $25,000.)

On top of that, all of this equipment needs to follow the sailors all around the world, to places like Belgium, Israel, and Brazil, where the competitions that are fundamental to an Olympic training program often take place. Then, they need a coach, a place to stay and a way to get to these places. Put that all together and a realistic budget quickly leaps into the $100,000+ territory.

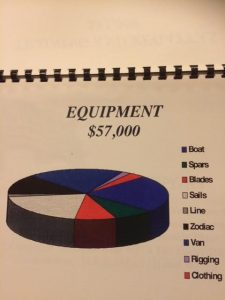

1996 Olympian Louise Gleason’s budget for sailing equipment, which does not include transport, lodging, or coaching. The same equipment costs much more today. Source: Louise Gleason

Unsurprisingly, money was a challenge for Barrows and Morris from the start. As a new team, they had to prove themselves before receiving any grants from the U.S. Olympic Committee, the U.S. Sailing Association, endorsements from corporate sponsors, or support from private donors.

This meant that they were on their own, at least for some time.

“The first nine months were totally funded from what I had saved in Switzerland and from what was left over from Thomas’s previous Olympic sailing [Barrows had competed in the 2008 Olympics in Beijing]… It was really grassroots, especially in that year, in terms of funding,” recounts Morris.

In the first two years, Morris says that he and Barrows spent less than $80,000. That includes all campaign and living costs for two people. The median household income (a number which represents a household’s income in a single year) was $59,039 in 2016, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

The money shortage they had in this time created a major obstacle: eventually, they would have to make up for the precious training time they lost while fundraising and budgeting in the first several months of their campaign. Morris estimates that he and Barrows spent 50 percent of the time of their campaign fundraising, budgeting, planning, and completing other logistical tasks.

Just as the first few years of a child’s life are the most essential to brain development, the most essential time of a campaign is the first few months, when teams develop basic, fundamental skills that carry over to each successive day of sailing. The pair spent most of this time trying to figure out how they would be able to afford the next week or month of sailing.

Just as the first few years of a child’s life are the most essential to brain development, the most essential time of a campaign is the first few months, when teams develop basic, fundamental skills that carry over to each successive day of sailing. The pair spent most of this time trying to figure out how they would be able to afford the next week or month of sailing.

According to Morris, it is “really crucial to spend a lot of time on the water at the beginning of the campaign. Unfortunately, that’s when you’re farthest from Olympics…,” he says. “It’s easier to fundraise when you get closer to the date.”

Yale sailing coach, former U.S. Sailing Olympic Committee Member, and 1996 Olympic hopeful, Zack Leonard, has sent many sailors off to pursue the Olympic dream, including Barrows and Morris. When asked about some of the challenges he saw Barrows and Morris face, he says, “They were really up against it financially even to begin.”

“They had to make a bunch of compromises,” he explains. Having limited resources meant they had to make a lot of decisions they wouldn’t have made “if they’d had every option,” as he put it.

In a perfect world, with an unlimited amount of funds, sailors pursuing an Olympic goal would own all of the newest equipment and spares, would travel to all of the top events, no matter where they were in the world – on direct flights that minimized time spent travelling – and would have a private coach travelling with them. This wasn’t the case for Barrows and Morris. They had to make compromises, as Leonard implies, about equipment, travelling and coaching.

At the end of 2013, Barrows and Morris considered ending their campaign. “We basically ran out of money and almost stopped sailing in early 2014.” Fortunately, around this time, they received a small grant from US Sailing, just enough to keep them from quitting.

Overturned, Again

This grant was just enough for them to continue, but they struggled financially through the summer of 2015. “We basically hung on by a thread all the way through our campaign,” Morris said.

In August of that year, they hit a second major roadblock. They had returned to the Virgin Islands for a training camp, and had a “minor” capsize on the way in. To avoid putting a hole in his expensive sail, Morris jumped off the boat and landed with an arm fully extended.

He was injured. He had heard of a couple of sailors who’d had this type of incident, and for many it was “career-ending.”

The first few doctors Morris visited told him that he would absolutely need surgery and at least seven months of recovery time. This was “not an option,” in Morris’ view.

Shortly thereafter, he was connected with new doctors and physical therapists who found a non-surgical solution, one which involved an intense several-month-long period of rehabilitation.

Morris showed signs of a miraculously speedy recovery a few weeks after beginning rehab. His doctors were surprised, he explains: he “shouldn’t be able to put [his] arm over [his] shoulder a couple of weeks after having this injury,” they said.

And so, Morris recovered and he got back in the boat a month-and-a-half after facing what seemed to be an impossible situation. But yet again, they had missed a crucial period of training. Just three months remained before they would compete in the first of two Olympic selection events, the Sailing World Cup in Miami.

Crunch Time

In the time of Morris’ injury, they had a lost a few of their training partners, so they were forced to come up with a plan that would optimize their chance of success at the upcoming event. They decided to “over-train” by themselves.

In the sport of sailing, in which a race is won by sailing around a set course in a shorter time than your competitors, boat speed is essential. The 49er is an especially technical boat, meaning that the many pieces of equipment and the ways in which you set up that equipment can significantly affect your speed relative to competitors. Boat speed is most easily tested by sailing with or against another boat.

This strategic – or perhaps forced – decision to train alone, with no boats to test speed with, is what they ultimately attribute to their success at the Olympic trials. Not being distracted by another boat meant they were able to diligently practice in the wind and water conditions they expected to see at the trials. “We felt that we silently made a huge jump in the last month,” says Morris.

Going into the trials, they knew they were in a position to win. “We felt like we had done everything we possibly could have going into the event. The teams that didn’t feel that way melted away. There were five teams that could have qualified, and there was definitely a favorite [this was the team of Brad Funk and Trevor Bird, who had previously completed two Olympic campaigns]. It was anyone’s game.”

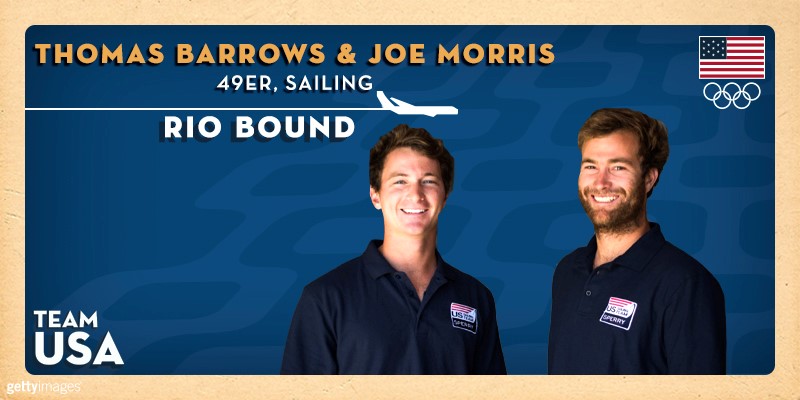

In February, at the conclusion of the 49er World Championship in Clearwater, Fla., they won U.S. Olympic selection.

It was an amazing feat, Leonard said. “It was a miracle that they won the trials having a disadvantage financially, doing less sailing than others; that they caught up to where they were competitive, then had this injury, then somehow had mental strength to pull it together and sail a lot of really good events leading up to trials.”

A little known fact is that they hadn’t paid off their boat – the boat that they would win the trials with – until 24 hours before the event.

Morris recounts, “We were waiting on donations that people had promised. Up until two days before the trials, we hadn’t paid off the only new boat Thomas and I had ever owned -not just in Olympic sailing, but in our entire lives. We had bought it one month before the trials, and we hadn’t paid it off… we only got the money 24 hours before the trials, and then we went on to win.”

Let the Games Begin

Barrows and Morris had finally proven themselves to be the top Men’s 49er team in the country. Now, they had to train to beat the top Men’s 49er teams in the world.

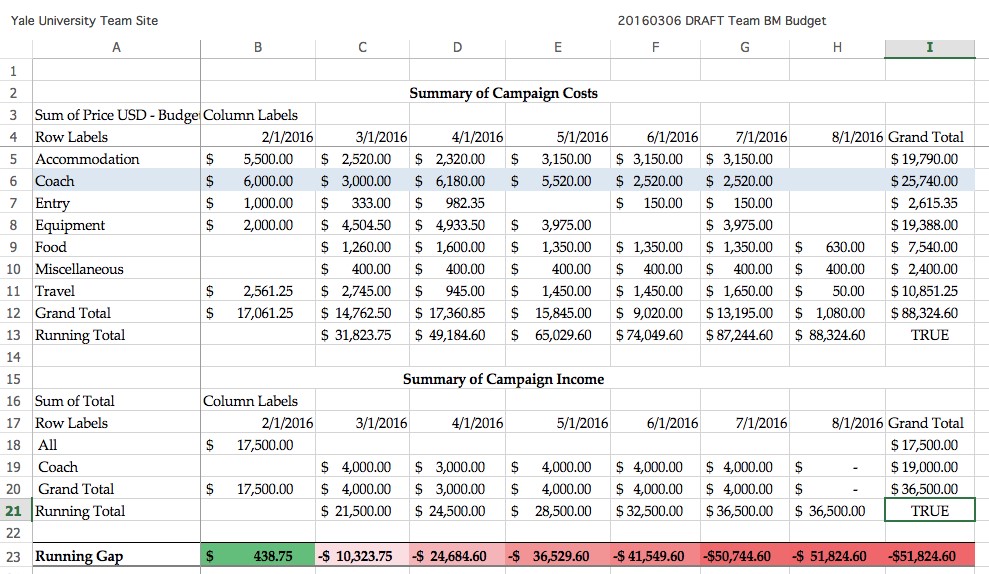

Competing on the world stage meant that what they had been doing so far in terms of training and funding would just not cut it. Morris says that between February and August 2016, their budget would grow 100% – to $95,000 – meaning that they would spend essentially the same amount of money in these five months that they had spent in their entire three-year campaign.

On the upside, qualifying for the Games meant qualifying for their first major grant from the U.S. Sailing Association… of $25,000, according to Morris. $25,000, however, is just over a quarter of the total funding they would need.

Barrows and Morris’s costs and income from February 2016 to August 2016. Campaign costs were approximately $88,000. They had only raised $36,500 as of July 2016.

Fortunately, as Morris puts it, “It is easier to fundraise when you get closer to the date. A couple of families supported us at the end and basically turned our campaign around. The funds allowed us to train full-time without really worrying about money. We even hired a private coach at the end.”

The funds, it turns out, would not make up for the lost time at the beginning of their campaign and in August 2015, when Morris sustained the injury, according to Leonard.

At the Games, they placed 19th out of 20.

Morris didn’t see their performance as a defeat. “We knew that we were on fringe of being in top 20 of world,” he explained. “[The result is] something I’m very proud of. Especially the way we faced all odds.”

Teammate and friend of Barrows and Morris and 2014 College Sailor of the Year Graham Landy ’15, who “followed their campaign closely,” was impressed with all they managed to accomplish given the challenges. “Given their resources, their training program was very smart.”

The message, it seems, is not that their performance was a disappointment. The take-away is that it was all they could have hoped to achieve given the several challenges they faced. “We realized we weren’t going to be the best-funded team, with the most experience, but we did a good job of money-balling the situation and staying positive and relying on the strength of our team,” says Morris.

There-in lies the problem: Should two decorated sailors with an incredible amount of potential to succeed on the world stage have to “money-ball” an Olympic campaign?

Born 25 Years Too Late?

Barrows and Morris are not the only Olympic hopefuls in the United States forced to spend much of their Olympic campaign raising money, thinking about money, and wondering whether they will be able to complete the next day or week of training.

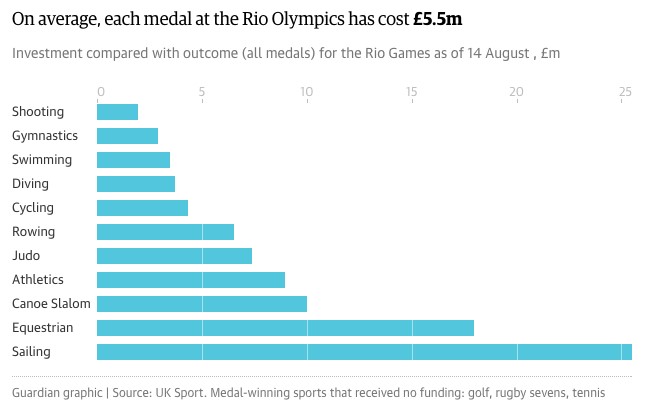

After all, the U.S. Olympic Team does not have the resources of the British Olympic Team. For the 2016 Games, Team Great Britain (GB) was awarded 274 million pounds by the British government and national lottery. The sailing team alone had a budget of 25.5 million pounds for Rio and has already been awarded 26.2 million pounds for Tokyo 2020.

These extreme levels of funding paid off. Team GB earned 67 medals in the 2016 Games; three in sailing – two Gold, one Silver. A nation with a population one-fifth of the size of the United States earned over one-half of the medals overall (121 for Team USA, 67 for Team GB).

In comparison, the U.S. Olympic Committee (USOC) awarded $1 million to the U.S. Sailing Association (USSA) in 2015. The USSA received similar levels of funding for the previous two years… and the U.S. won one medal in Rio – a bronze.

2012 was an even bigger disappointment: for the first time since the 1936 Berlin Games, the U.S. won no medals in the sport of sailing.

While it is unrealistic to expect that the USOC will ever generate a budget like that of the British team, it is clear that there are fundamental differences in the funding schemes of the two teams.

It is also evident that the U.S. has fallen in performance in recent years while the British team has maintained a medal-winning strategy.

JJ Fetter, Yale class of 1984, is an Olympic Silver and Bronze medalist in the Women’s 470 (the 470, like the 49er, is a two-person, technically-oriented boat). She is currently a member of the U.S. Sailing Olympic Committee, which she was tapped for in 2012, shortly after the disappointing performance of the U.S. Olympic Sailing Team in London.

Fetter attributes some of the U.S.’s performance in 2012 and 2016 to the team’s failure to recognize a major a major shift in the sport: Olympic sailing became more professional, requiring 300 day per year campaigns – as opposed to the 180 day per year campaigns run the 1980s and 1990s – and exponentially larger budgets.

Fetter says, “Nobody really trained full-time [in the 80s and 90s]… back in the day, we were training as much as any of our top competitors and also had time to do part-time jobs at home to make ends meet and organize fundraising events.”

“Joe [Morris]’s top competitors are full-time sailing and training.” For these sailors, she furthers, “someone else is dealing with the logistics; someone else is getting them sponsorships, paying their bills. The athlete can focus full-time on training and racing. In the U.S., our sailors are having to do all those things; basically three or four jobs. They are their own campaign managers.”

Louise Gleason, Yale class of 1991, represented the United States in the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta, placing fourth in the Women’s 470. She agrees with Fetter, saying, “The level of sailing [now] is so much higher; it’s more professional.”

Putting numbers to words, Gleason says that the budget for her 1996 campaign was $250,000. Fetter estimates that she spent close to $200,000 in her 1992 campaign, but she says that her costs were significantly lowered because she was able to split lodging, travelling, and equipment transport costs with the group of sailors who were also pursuing campaigns at the time. Today, Morris estimates, a realistic budget for a medal-winning campaign in the 49er would be $600,000 (while the 49er and the 470 are different boats, the cost of sailing are comparable).

Fetter jokes, “Joe and Thomas were just born 25 years too late… Frankly, their model was the way you won Olympic medals in the 70s or 80s!”

Moving Forward

The U.S. Sailing Association is working to address the recent underperformance of the U.S. Olympic Team.

On top of a major leadership change – the hiring of a two-time gold medalist to lead the U.S. Olympic Sailing Team – the Olympic committee has set out a two-part plan aimed at developing youth sailors and providing sailors that show potential with better funding. Their hope is to help sailors like Barrows and Morris perform to their potential on the world stage and to encourage younger sailors to pursue Olympic Sailing.

The first part of the plan, Fetter explains, is the creation of an Olympic Development Program to provide youth sailors with access to high-performance Olympic-type boats and high-level coaching as they make the transition from youth sailing to college sailing to Olympic sailing.

The second part, she says, is to execute a “robust fundraising program to be able to support people like Graham [Landy], with [a high] level of talent to help launch them into an Olympic program.”

(Landy was the 2014 captain of the Yale sailing team, leading his team to several national championships, winning four All-American Awards, and the national College Sailor of the Year award in Spring 2014. On his decision to not pursue an Olympic campaign, he says, “While sailing had been such a big part of my life growing up and through college I wasn’t willing to jump headfirst into a program with so much turnover and an unclear path.”)

While the Olympic sailing program has a long way to go in terms of getting back on the medal track, many up and coming sailors are willing to overlook this fact – not much would stop them from working toward their Olympic goal.

Current Yale Co-ed Sailing Captain and 2015 ICSA Single-Handed National Champion Malcolm Lamphere is pursuing a berth at the 2020 Olympic Games in the Laser, even though he knows how hard it will be. He says, “I wouldn’t describe Olympic sailing as a career path… I would describe it as a dream. It is an ultimate goal to represent your country and compete at the highest level.”

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.