Revolutionizing transoceanic navigation

Published on January 11th, 2018

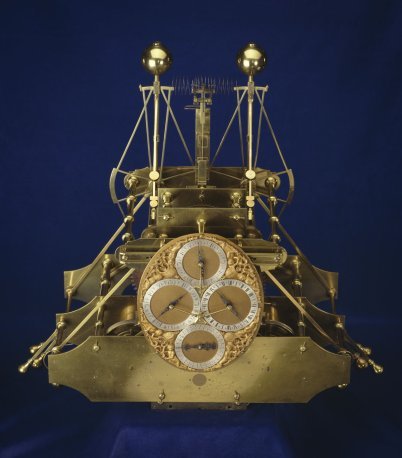

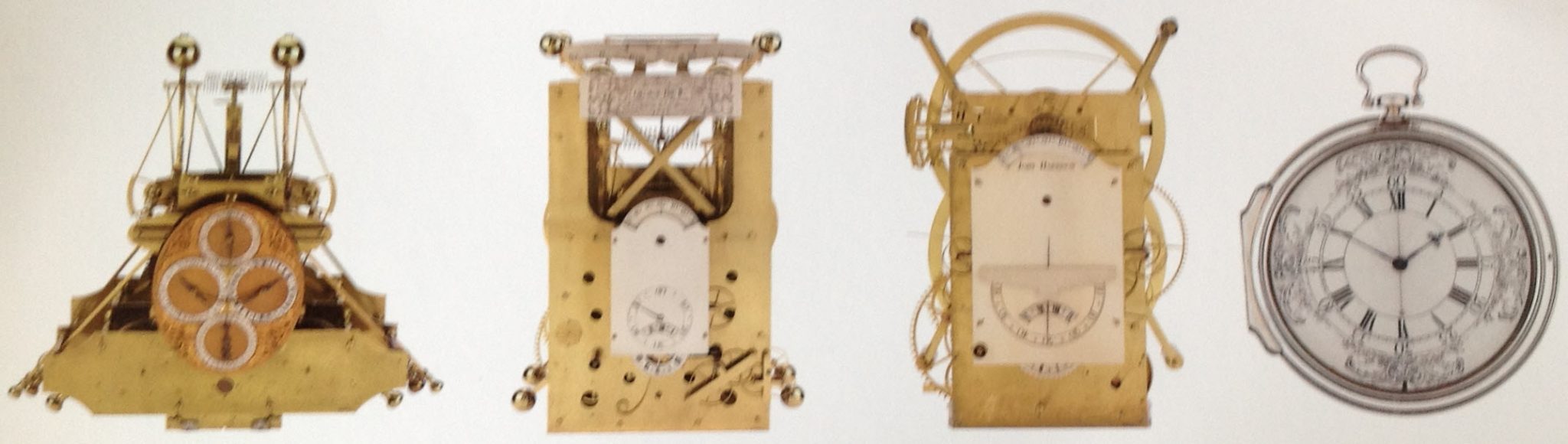

In the early 1700s, John Harrison invented a remarkable and revolutionary device – a clock – that a ship could carry to accurately calculate longitude. He called his clock the H-1, and its invention puts Harrison in the pantheon of the world’s greatest inventors.

The inability to calculate longitude had led to countless shipwrecks over the prior centuries as sailing technology had enabled increasingly ambitious transoceanic trading voyages. These wrecks ended countless lives and destroyed untold fortunes, so much so that in 1707 the English Parliament offered a prize of £20,000, an enormous sum in that era, to anyone who could solve the longitude problem.

By 1737, the remarkable Mr. Harrison presented his solution to the commission charged with administering the prize and it was deemed satisfactory to everyone involved – except one person. Astonishingly, Harrison himself was unsatisfied by his solution and spent another two decades perfecting his invention.

The same exacting personal standards and urge to tinker that had enabled him to solve the problem prevented him from accepting a prize for something that did not meet his own standards, even if it met the commission’s view.

Instead, Harrison pointed out the foibles of H-1. He was the only person in the room to say anything at all critical of the sea clock, which had not erred more than a few seconds in twenty-four hours to or from Lisbon on the trial run. Still, Harrison said it showed some ‘defects’ that he wanted to correct.

He conceded he needed to do a bit more tinkering with the mechanism. He could also make the clock a lot smaller, he thought. With another two years’ work, if the board could see its way clear to advancing him some funds for further development, he could produce another timekeeper. An even better timekeeper. And then he would come back to the board and request an official trial on a voyage to the West Indies. But not now.

The board gave its stamp of approval to an offer it couldn’t refuse. As for the £500 Harrison wanted as seed money, the board promised to pay half of it as soon as possible. Harrison could claim the other half once he had turned over the finished product to a ship’s captain of the Royal Navy, ready for a road test.

At that point, according to the agreement recorded in the minutes of the meeting, Harrison would either accompany the new timekeeper to the West Indies himself, or appoint ‘some proper Person’ to go in his stead.

By the time Harrison presented the new clock [called the H-2] to the Board of Longitude in January 1741, he was already disgusted with it. He gave the commissioners something of a repeat performance of his previous appearance before them: All he really wanted, he said, was their blessing to go home and try again.

As a result, H-2 never went to sea … [even though it] constituted a minor revolution in precision … [and] passed many rigorous tests with flying colors. The 1741-42 report of the Royal Society says that these tests subjected H-2 to heating, to cooling, and to being ‘agitated for many hours together, with greater violence than what it could receive from the motion of a ship in a storm.’

Not only did H-2 survive this drubbing but it won full backing from the Society … but it wasn’t good enough for Harrison. The same vicelike conviction that led him to his finest innovations — along his own lines of thinking, without regard for the opinions of others — rendered him deaf to praise. What did it matter what the Royal Society thought of H-2, if its mechanism did not pass muster with him?

Harrison, now a London resident and forty-eight years old, faded into his workshop and was hardly heard from during the nearly twenty years he devoted to the completion of H-3, which he called his ‘curious third machine.’ He emerged only to request and collect from the board occasional stipends of £500, as he slogged through the difficulties of transforming the bar-shaped balances of the first two timekeepers into the circular balance wheels that graced the third.

Harrison eventually claimed the prize, and his invention revolutionized transoceanic navigation.

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.