Splice Failure Linked to Fatality

Published on January 10th, 2019

For more than 35 years, Practical Sailor has been taking the guesswork out of boat and gear buying with bold, independent boat tests, and product-test reports for serious sailors and boaters. In this report, they remind us of the risks from poor rigging.

On the 4th of September 2015, Andrew Ashman was killed during an accidental jibe, when the boom delivered a fatal injury to the base of his neck during the 2015-16 Clipper Round the World Race. The boat, CV21 Ichor Coal, had been running in strong conditions, and yawing allowed the wind to get on the wrong side of the mainsail, as occasionally happens.

A preventer was rigged, but a strop securing a low friction ring turning block near the bow failed, allowing the boom to cross the cockpit unrestrained. On such highly engineered boats, how did this happen?

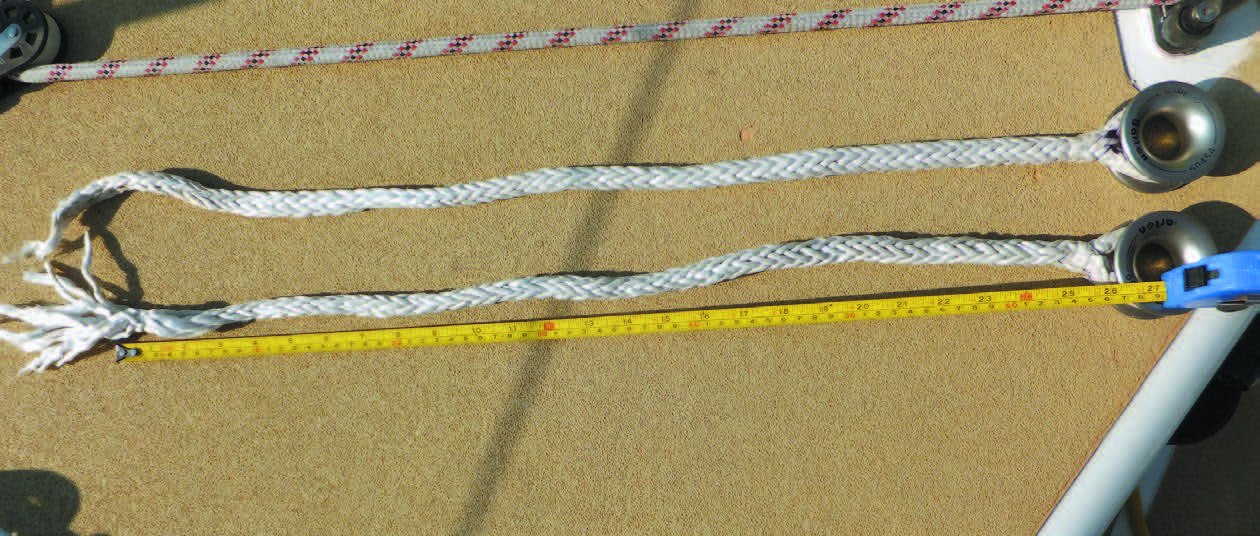

Instead of using two independent strops to handle the load off the preventer, the rigger on Ichor Coal used single long strop with low friction rings eye-spliced at each end. A Brummel lock (see image above) was added to keep the strop in place on the bow fitting where the strop was secured.

This type of Brummel can only hold about 40-60 percent of the breaking strength of the line. In addition, the preventer was led at a very acute angle to the boom (see PS June 2017, “The Best Prevention is a Preventer“)

According to Great Britain’s Marine Accident Investigation Board, the failure was traced to a poor choice of splice. High Modulous Polyetheylene (HMPE) ropes, like the Marlow D2 Racing Rope used on the Clipper boat or Amsteel, must be spliced using product specific procedures.

All common sailing knots will slip at a small percentage of breaking strength unless modified, and even then, the low stretch nature of HMPE makes them low strength (poor load sharing).

The standard method for forming eyes in hollow braid ropes, like that in question, is a long bury splice, where the tail is about 72 line diameters long. Like a paper finger trap, the harder the rope pulls, the more the herring bone weave contracts on the buried tail.

To prevent the long bury splice from loosening as the rope flops around unloaded, the tail is locked in place at the base of the eye with either lock stitching or a Brummel lock. Neither adds much strength to the splice, and both are intended only to stabilize the splice when unloaded, something all splices can benefit from.

Because there was not enough space for a long bury on each tail, the rigger apparently relied on the Brummel lock alone to carry the load.

This decision was based on the misconception that a Brummel lock actually “locks” the lines together and can carry safely load. In actual fact, a single Brummel (two passes), such as used on Ichor Coal, can hold only 40-60 percent of breaking strength before failing, which it did.

A better construction, when space is limited, is two separate spliced loops, as used on manufactured products such as Harken LOOPS or pre-spliced low friction rings from Antal, Nautos, and others.

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.