R2AK: Shaping the truth of what is

Published on June 28th, 2019

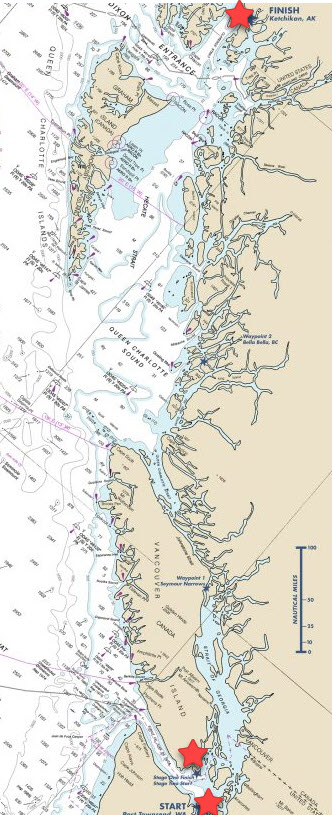

The 5th edition of the 750 mile Race to Alaska began June 3 with a 40-mile “proving stage” from Port Townsend, WA to Victoria, BC. For those that survived, they started the remaining 710 miles on June 6 to Ketchikan, AK.

While the winners finished on June 10, the R2AK is more than chasing pickle dishes, but even for the adventure hungry, all good things must come to an end. Here is the final report on June 28 from Daniel Evans, RaceBoss:

It’s sunny today in Ketchikan. The view from town reaches across Pennock to Gravina Island since the cruise ship schedule was reduced from six to one visiting ship. Locals are walking around in t-shirts and cutoff jeans complaining about how hot it is, because it’s 77 degrees.

All this is to say, I’m writing in a Ketchikan most people have never known. I’m positioned in an alternate reality without heavy rain, stormy southeasterlies, or throngs of tourists emptying from ships in a hoard so dense that all of Revillagigedo Island tilts just a bit towards the docks.

These are things of the past, a story, until something proves it different.

R2AK 2019 is an object in our collective rear view mirror, appearing at different distances for each and every team. It’s been three days since Team Wee Free Men row/paddled into Thomas Basin claiming finish line last place honors, after a 48-hour push involving the tedium of rowing across the placid Dixon Entrance.

A placid tedium not seen by many teams including Holopuni who suffered a crippling and confused sea strong enough to rip off their hatch cover, flood the boat, and turn the race into a rescue. Dixon Entrance, like Seymour Narrows, Fitzhugh Sound, Straits Queen Charlotte, and Georgia—hell, anyplace but the 32-stair jog of the Le Mans start on the Victoria esplanade—will have a completely different telling depending on which team is telling the tale.

Back in Dixon Entrance, Team Sail Like a Girl will tell a story about broaching so hard that a crew floats free of the boat atop the ensuing rush of water while Backwards AF recounts gliding through a calm. Pear Shaped Racing describes hitting four logs and losing their electronics while Wee Free Men paints the Entrance as rolling and greasy. Which is true?

Forty-two teams tried R2AK in 2019, and now we have 42 unique stories.

I, like the 17 teams who never completed the race, also have my own story: a collection of late night conversations, finish line tall tales, ad hoc interviews, tearful phone calls, yacht club banter, and two or three times the chance to witness teams huddled together, comparing notes, and taking a moment with another human who kinda gets what was just accomplished.

However, I can’t help but focus on the teams who didn’t make it to Ketchikan, because let’s be honest; it’s much harder to accept loss than embrace victory. There is something about re-calibrating your expectations akin to swallowing beach rocks.

Like Thor of Team Funky Dory calling from Bella Bella to say that in spite of months of working on the boat, a groundswell of community and financial support, after all the stoppered leaks, the cheers from ashore and across the country, the encouragement from fellow teams—they could go no further. They put everything out there and came up short of a dream to find it replaced with another something. An accomplishment they never expected and a satisfaction they are still trying to understand.

How can a person be satisfied after pushing up against a challenge, giving everything—100% of their skill, tenacity, courage, spirit, and hope—yet still come up short?

In struggles as deep as these, you find identity. You go to a place where you see yourself for the first time; your relationships, your ego, humility, greed, compassion, leadership, thresholds for pain and cold are all shown in stark honesty. You get a chance to see the true parts of yourself for the first time. Or maybe the first time in a long time. In this, everyone’s story is valid. What we celebrate is the truth or fiction of a person’s story, because who can define the success or failure of a challenge but the person whose heart it lives in?

Yet, it still doesn’t land a team in Ketchikan. Maybe it’s the moment when a person realizes Ketchikan will never be a part of their R2AK story that makes the rock so hard to swallow. Then they look at their hands, hear their breath, touch the combing of the boat, and realize what is all of them is there right now, it’s present and waiting for the next move. Given what’s left, in the ashes of lost expectations, could you appreciate what you had done? Have you? For better or for worse, there you are.

Unless you’re Christian of Team Try Baby Tri. If you’re Christian, you leave your boat on Denny Island to fly to San Francisco for your movie premiere. Then you get a call from me.

ME: “Christian, I got your message. So you’re headed to California?”

HIM: “Yup, just for the premiere, then I’m coming back and going to sail until the Grim Sweeper catches me. I’m beating that boat!”

ME:“Christian, it’s going to sweep you tomorrow.”

HIM: “Oh! Well, I love the race. I’m going to come back next year. I had the best time.”

ME: “Awesome, Christian. Next time, call your mom more. She worries.”

For me, the beauty of Race to Alaska is that all these stories, reasons, and truths can co-exist. Because while boats have different experiences, hearts speak the same language. I often wonder how a race such as this can bring such a disparate yet unionized group of people together—in fans, racers and supporters.

There is this little bromide attributed to Buddha that says, “If the cuff of your sleeve touches that of another on the sidewalk, you have lived a thousand lives with them.” It speaks to a tuning, like a wave which shapes a rock over time. We are all part of this race because it calls to us.

What we each get is a story, perhaps different in the telling, but matching the same rhythms. We get lessons and friends and shame and triumph. Joy and giggles and drinks and diversion. We get to learn nothing at all or completely change our lives. We get to prove something to our father, our mother, or meet a challenge greater than ourselves. We get to R2AK, because R2AK is us.

Thank you all for this year, this experience, and at least 42 new stories that shape the truth of Race to Alaska.

Race details – Team list – Tracker – Results – Facebook – Instagram

For the second year in a row, a monohull has taken line honors. Here’s the history:

2015 – 5 days 1 hour 55 min – Elsie Piddock

2016 – 3 days 20 hour 13 minutes – Mad Dog

2017 – 4 days 3 hour 5 minutes – Freeburd

2018 – 6 days 13 hour 17 minutes – First Federal’s Sail Like a Girl

2019 – 4 days 3 hours 56 minutes – Angry Beaver – Sailing Skiff Foundation

Background:

Background:

Race to Alaska, now in its 5th year, follows the same rules which launched this madness. No motor, no support, through wild frontier, navigating by sail or peddle/paddle (but at some point both) the 750 cold water miles from Port Townsend, Washington to Ketchikan, Alaska.

To save people from themselves, and possibly fulfill event insurance coverage requirements, the distance is divided into two stages. Anyone that completes the 40-mile crossing from Port Townsend to Victoria, BC can pass Go and proceed. Those that fail Stage 1 go to R2AK Jail. Their race is done.

Stage 1 Race start: 0500 June 3rd, Port Townsend, Washington

Stage 2 Race start: 1200 June 6th, Victoria, BC

There is $10,000 if you finish first, a set of steak knives if you’re second. Cathartic elation if you can simply complete the course. R2AK is a self-supported race with no supply drops and no safety net. Any boat without an engine can enter.

Last year 37 teams were accepted and 21 finished.

Source: Race to Alaska

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.