Revealing the recycling myth for plastic

Published on April 21st, 2020

As an event to demonstrate support for environmental protection, Earth Day on April 22 is an annual reminder for those of us that use the earth (and that’s all of us). As enthusiasts of a sport reliant on water, that puts sailors in the front row of those that need to lean in.

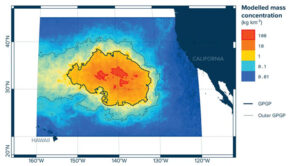

When an estimated 17.6 billion pounds of plastic enters our oceans every year, that’s the equivalent of dumping a garbage truck’s worth of plastic into the water every minute. With only 9% of all plastic waste generated being properly recycled, recycling alone is not enough to solve the plastic crisis.

With 2020 as the 50 year anniversary of Earth Day, this report by Emily Petsko for the ocean conservation organization Oceana reveals the recycling myth:

Three arrows chasing each other in a triangular loop: For decades, the consuming public has recognized this symbol as a promise that “this package can and will be recycled.” However, the perceived promise of those interlocking arrows is a hollow one, as most plastic products – save for those with the numbers one and two on the bottom – are not recycled in any significant amount.

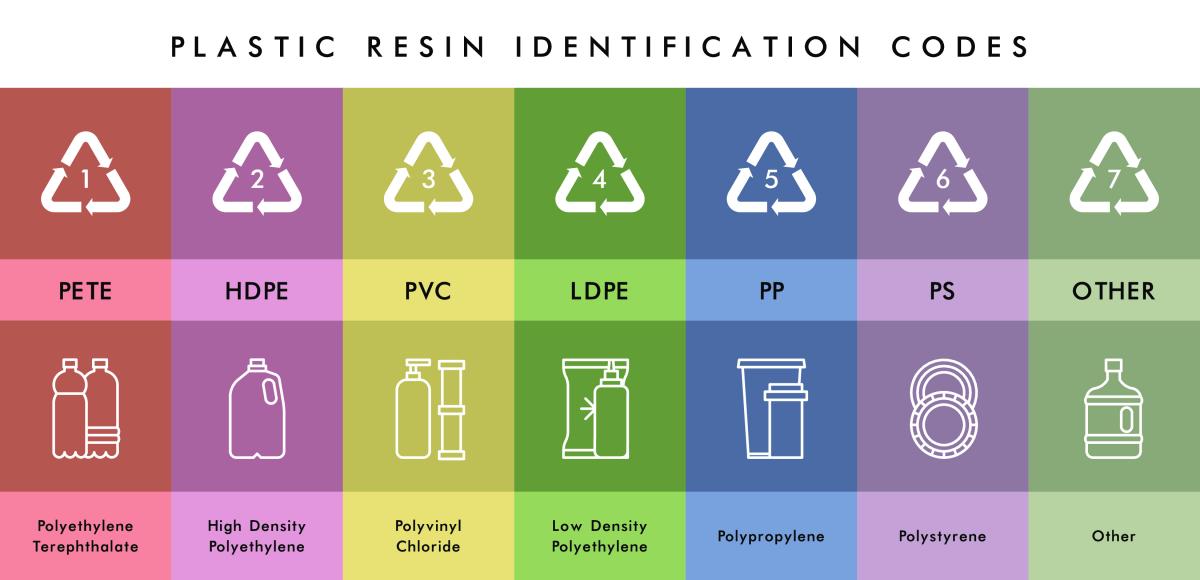

The arrows with numbers that you find on your soda bottle (usually a No. 1 plastic made with PET, or polyethylene terephthalate), your yogurt tub (often a No. 5 made with polypropylene), and other everyday products are part of the Resin Identification Code (RIC) system that was created by and for the plastics industry in 1988.

Each number signifies a different category of plastics – of which there are seven in total – and this system was designed to tell recycling facilities what type of resin can be found in any given object. As it turns out, they were never a guarantee that the item in question would be recycled.

“Resin Identification Codes are not ‘recycle codes,’” ASTM International, the organization that administers the RIC system, writes on its website. “The use of a Resin Identification Code on a manufactured plastic article does not imply that the article is recycled or that there are systems in place to effectively process the article for reclamation or re-use.”

If you find this surprising, you’re not alone.

According to a survey of 2,000 Americans that was conducted by the Consumer Brands Association last year, 68% of respondents said they thought any item bearing an RIC would be recyclable.

(In an effort to reduce confusion, ASTM International altered the symbols in 2013, replacing the arrows with a solid triangle. However, manufacturers aren’t required to change their equipment to incorporate the new symbol, which is why you still see the arrows on many plastic products.)

Consumers widely misinterpret RICs and, as a result, they “wish-cycle.” Many well-meaning and hopeful consumers place any plastic item with an RIC in their recycling bin, regardless of whether they will actually be recycled.

So instead of resulting in more plastic being recycled, this approach all too often slows down the sorting process, drives up recycling costs, results in higher rates of contamination, and ultimately sends more waste to landfills, incinerators, and natural environments. Our recycling wishes, in other words, are being turned into garbage.

The myth surrounding RICs makes us believe that plastic is recycled far more often than it actually is. In fact, only 9% of all the plastic waste ever created has been recycled, and many of those recycled items belong to just two of the seven resin categories.

Susan Freinkel, author of the 2011 book Plastic: A Toxic Love Story, told Oceana that “the only plastics recycled in any significant amounts are No. 1 and No. 2 plastics, which cover soda and water bottles, as well as milk, juice, and detergent jugs.”

A new report by Greenpeace takes this a step further, arguing that No. 1 and No. 2 bottles and jugs are the only plastics that can legitimately be called “recyclable” and advertised as such. That’s because they are the only resins that have “sufficient market demand and domestic recycling/reprocessing capacity,” according to the report. The remaining municipal plastic waste is often referred to as “mixed plastic.”

Ever since China shuts its borders to the world’s mixed plastics in 2018, the U.S. has struggled to find a market for its plastic waste, especially No. 3 through No. 7 plastics, which are less valuable.

Some states (like Florida) and cities (like Erie, Pennsylvania) have urged residents to recycle only plastic bottles and jugs, which are generally made of PET (a No. 1 plastic) or HDPE (a No. 2 plastic). Cuyahoga County, the second most populous county in Ohio and home to Cleveland, has adopted this approach.

In 2015, local authorities told residents to ignore the numbers and instead sort by shape, placing only higher-value plastic waste like bottles, jugs, tubs, and jars in their recycling bin. After China’s plastic import ban went into effect, the list of items you could actually recycle in Cuyahoga County got smaller. Now, only bottles and jugs (like laundry detergent containers) are accepted.

“[RICs] were never meant to determine recyclability,” says Diane Bickett, executive director of the Cuyahoga County Solid Waste District, which serves as a countywide resource for recycling information. “People have been confused about that since 1988, when they started appearing on the bottom of the packaging.”

Even with Cuyahoga County’s efforts, roughly a quarter of all items tossed in recycling bins are contaminated, and some of that is because of the unrecyclable plastics that are still being “wish-cycled.” In response, the Solid Waste District’s communication efforts are focused on getting a new message across: Waste reduction.

“We’re just trying to tell people that we’re not going to recycle our way out of our waste problem,” Bickett says. “There’s just too much material, and too much waste, being generated.”

Freinkel, in her book, talked to a plastic industry spokesperson who referred to recycling as “a guilt eraser.” The spokesperson told Freinkel that “as soon as they [consumers] recycle your product, they feel better about it.”

“Recycling,” writes Freinkel, “assures people that plastic isn’t just an infernal hanger-on; it has a useful afterlife.”

Of course, that is also a myth. We all need to separate the hopeful and increasingly fantastical act of recycling from the reality of plastic pollution. Recent data indicates that our recycling wishes, hopes, and dreams – perhaps driven in part by myths surrounding RICs – will not stop plastic from entering our oceans.

Instead, if we truly want to protect the environment and marine life, we need to campaign for more plastic-free choices and zones, and for the reduction of plastic production and pollution.

There are a lot of easy and creative ways to reuse some of the plastic items we already have in our homes. Use old milk and juice containers to water plants, save peanut butter jars and use them to store snacks and use old salad dressing containers to mix and store homemade dressings.

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.