A little too much excitement

Published on September 14th, 2020

Following on from reports by Martha Parker and Kate Wilson who experienced an unexpected storm which plastered New England sailors on a summer weekday evening, meteorologist Mark Thornton (LakeErieWX) reviews what led to a little too much excitement on Narragansett Bay.

Introduction

Thunderstorms and sailboat racing don’t mix. Sometimes the rain from a thunderstorm results in a prolonged period of light and variable winds, or perhaps no wind at all. At other times, a storm wreaks havoc on the racecourse by producing incredibly strong winds, blinding rain, and steep waves. Neither version promotes finishing a race in a fast or safe manner.

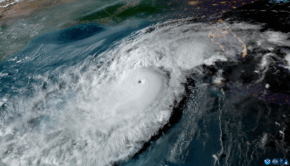

Sailors competing in the final race of the Jamestown Yacht Club’s (JYC) Summer Series experienced the “furious winds” version of a thunderstorm when a cold front rolled over Narragansett Bay (Rhode Island) on Tuesday, August 25, 2020. Before we delve into the details of that storm, let’s cover a couple of thunderstorm basics.

A Little Background

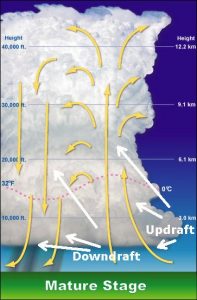

During their mature phase, all thunderstorms have an updraft and downdraft (Figure 1). The updraft sustains the storm by delivering warm, moist air to its upper levels. The speed of an updraft – a measure of the storm’s strength – is determined by the temperature difference between the warmer air inside the updraft and the cooler air surrounding it. It is not uncommon for an updraft to reach 100 mph. The larger the temperature difference, the faster the air ascends within the updraft.

A storm’s downdraft is the descending flow of rain-cooled air. In contrast to an updraft, air within a downdraft is colder and denser than the surrounding air. Downdrafts form when precipitation particles such as water droplets, ice crystals, and hail become too heavy to remain suspended by the storm’s updraft and begin to fall.

As they fall, some of the particles evaporate before reaching the ground, which further cools and increases the density of the air within the downdraft. Since the speed of a downdraft is determined by the difference in temperature between the air within the downdraft and the surrounding air, evaporational cooling can dramatically increase the speed and destructive potential of the downdraft.

The National Weather Service (NWS) does not have an official threshold for a downburst, but a downburst is simply a strong downdraft. Downbursts may be further subdivided into microbursts and macrobursts depending on the duration of the strong winds and the size of the affected area. A microburst impacts an area less than 2.5 miles wide for fewer than five minutes. A macroburst affects an area greater than 2.5 miles wide and lasts more than five minutes. – Full story

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.