Science and The Ocean Race

Published on March 26th, 2023

After a long hiatus, The Ocean Race is back, but this year, as reported by Yvonne Gordon of the Guardian, while dodging icebergs, cracking masts and suffering the occasional ‘hull sandwich failure’, the teams are gathering crucial data from places even research vessels rarely reach.

The Southern Ocean is not somewhere most people choose to spend an hour, let alone a month. Circling the icy continent of Antarctica, it is the planet’s wildest and most remote ocean. Point Nemo, just to the north in the South Pacific, is the farthest location from land on Earth, 1,670 miles (2,688km) away from the closest shore. The nearest humans are generally those in the International Space Station when it passes overhead.

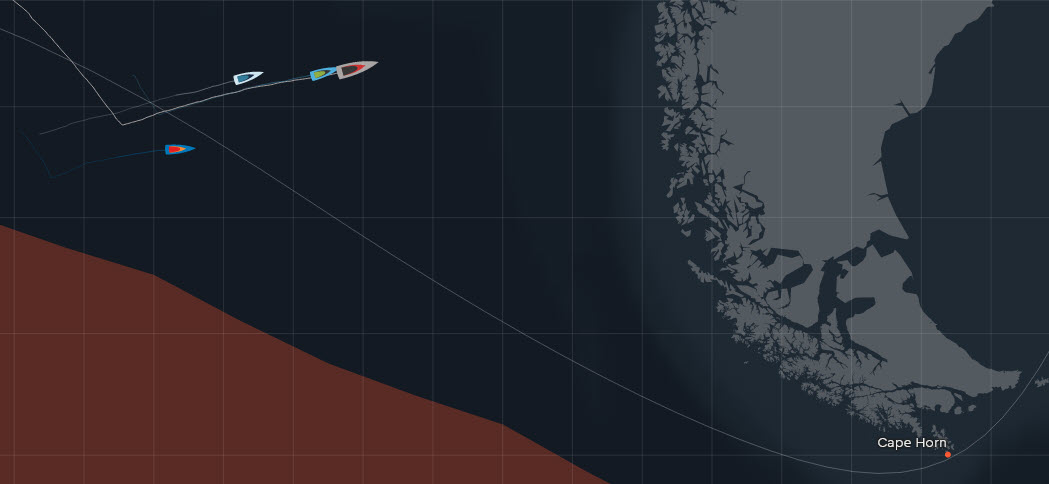

But, four sailing teams came through that part of the world, part of the marathon race round the bottom of the Earth, from Cape Town in South Africa to Itajaí in Brazil.

By the time these 18-metre (60ft) Imoca monohull sailing yachts neared Point Nemo, the five sailors on each boat had already been at sea for 23 days, with another two weeks to go before they reach port in early April. And this is just leg three, the longest portion of the even longer Ocean Race, a 32,000-nautical-mile dash around the world that started in January and finishes in July.

Competition is fierce and racing is close, even after three weeks at sea. Boat speeds on leg three so far have been up to 40.5 knots, the equivalent of gale force winds, and the vessels have, subject to ratification, broken the 24-hour distance record multiple times. The crews survive on freeze-dried food (rehydrated with hot water from a kettle, there’s no kitchen), and operate a four-hour alternating watch system. Nobody gets much sleep. The toilet is a bucket.

The dangers are unpredictable. Winds in the Southern Ocean can reach up to 70 knots and hitting an iceberg at speed would be catastrophic, so the boats have to steer clear of an ice exclusion zone around Antarctica. On March 1, the Team Malizia crew discovered a crack at the top of the mast, requiring one of them to climb up 28 meters in rough seas to patch it over in the middle of the night.

Guyot Environnement – Team Europe had to abandon leg three completely after suffering a “hull sandwich failure”, spending three nervous days sailing 600 nautical miles back to Cape Town for repairs. The last time Team Holcim-PRB’s skipper Kevin Escoffier raced here, his boat broke in half and sank and he was rescued from his life raft.

But while The Ocean Race is sometimes known as the toughest, and certainly the longest, professional sporting event in the world, an event that began in 1973 as the Whitbread Round the World Race then became the Volvo Ocean Race, and which attracts professional sailors of the highest level who join mixed crews every few years on sponsored teams to vie for an overall trophy (there is no cash prize), this year scientists have smelled an opportunity for them to benefit as well.

Because the boats visit the most remote part of the ocean, which even scientific vessels struggle to access, this year the crews will seed scientific instruments all around Antarctica, aiming to measure 15 different types of environmental data, from ocean temperature and atmospheric indicators to concentrations of microplastic.

Information from the devices will help with everything from weather forecasting to insights into the climate emergency. The Southern Ocean is one of the planet’s largest carbon dioxide sinks, for example, but its inaccessibility has meant that there is relatively little CO2 data available.

“The Southern Ocean is a very important driver of climate on a global scale [but] there is very little data,” says Toste Tanhua, chemical oceanographer at Geomar Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research in Kiel, Germany. “Data from the sailing races in the Southern Ocean is very important for us to understand the uptake of carbon dioxide by the ocean.”

Each boat is equipped with weather sensors on board that measure wind speed and direction, barometric pressure and air temperature. Each team will drop two surface drifter buoys provided by organisations such as Météo-France and the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which capture data to help the World Meteorological Organization study ocean currents and forecast extreme weather events such as hurricanes.

A second type of buoy, the Argo profiler, deployed by Team Malizia in leg two, operates below the surface at depths of up to 2km, moving slowly with deep currents and transmitting information every 10 days. The data is used for climate analysis as well as for long-range weather forecasts.

Meanwhile, 11th Hour Racing Team and Team Malizia are using OceanPacks to take regular water samples to measure the levels of carbon dioxide, oxygen, salinity and temperature, to be analyzed in Germany and fed to Socat, the Surface Ocean CO2 Atlas. Live dashboards give snapshots of the data as it is collected out at sea.

Tanhua says the fresh data reveals new patterns. For example, it shows how carbon dioxide varies over a year, higher when the water warms up in summer, lower during a phytoplankton bloom. It also shows how the ocean takes carbon from the surface and transports it into the depths. “In the Southern Ocean, you have three major frontal systems where water is either going down vertically (sinking) or coming up,” Toste says.

“That has very different carbon levels. Eddies also transport carbon up and down.” Scientists will now be able to observe these fronts and eddies up close, compare with satellite data and fill in the gaps.

The boats are also sampling trace elements such as iron, zinc, copper, cadmium, nickel and manganese, which are essential for the growth of plankton. Not only is plankton the base of the food chain, but phytoplankton are responsible for most of the transfer of CO2 from the atmosphere to the ocean.

“This data is extremely important,” says Dr Arne Bratkič, environmental biogeochemist at the University of Lleida, Spain, who analyses the trace element results. “It is important to know how much food is available for animals that will feed on phytoplankton eventually, and how much CO2 the phytoplankton is going to absorb from the atmosphere.”

Bratkič says that sampling such as this normally requires dedicated scientific voyages, on which places are limited and expensive. The Ocean Race is a way of testing investigations on non-scientific platforms at sea. “We are paying attention to the design of the samplers – what works and what does not,” says Bratkič. “It’s really exciting.”

To add to the plankton study, Team Biotherm is working with the Tara Ocean Foundation to study ocean biodiversity, and the sailors have an automated onboard microscope to record images and provide insights into the diversity of phytoplankton species. The more data we have, the more accurately we can understand the ocean’s capacity to cope with climate change. – Full story

Race details – Route – Tracker – Teams – Content from the boats – YouTube

IMOCA: Boat, Design, Skipper, Launch date

• Guyot Environnement – Team Europe (VPLP Verdier); Benjamin Dutreux (FRA)/Robert Stanjek (GER); September 1, 2015

• 11th Hour Racing Team (Guillaume Verdier); Charlie Enright (USA); August 24, 2021

• Holcim-PRB (Guillaume Verdier); Kevin Escoffier (FRA); May 8, 2022

• Team Malizia (VPLP); Boris Herrmann (GER); July 19, 2022

• Biotherm (Guillaume Verdier); Paul Meilhat (FRA); August 31 2022

The Ocean Race 2022-23 Race Schedule:

Alicante, Spain – Leg 1 (1900 nm) start: January 15, 2023

Cabo Verde – ETA: January 22; Leg 2 (4600 nm) start: January 25

Cape Town, South Africa – ETA: February 9; Leg 3 (12750 nm) start: February 26

Itajaí, Brazil – ETA: April 1; Leg 4 (5500 nm) start: April 23

Newport, RI, USA – ETA: May 10; Leg 5 (3500 nm) start: May 21

Aarhus, Denmark – ETA: May 30; Leg 6 (800 nm) start: June 8

Kiel, Germany (Fly-By) – June 9

The Hague, The Netherlands – ETA: June 11; Leg 7 (2200 nm) start: June 15

Genova, Italy – The Grand Finale – ETA: June 25, 2023; Final In-Port Race: July 1, 2023

The Ocean Race (formerly Volvo Ocean Race and Whitbread Round the World Race) was initially to be raced in two classes of boats: the high-performance, foiling, IMOCA 60 class and the one-design VO65 class which has been used for the last two editions of the race.

However, only the IMOCAs will be racing round the world while the VO65s will race in The Ocean Race VO65 Sprint which competes in Legs 1, 6, and 7 of The Ocean Race course.

Additionally, The Ocean Race also features the In-Port Series with races at seven of the course’s stopover cities around the world which allow local fans to get up close and personal to the teams as they battle it out around a short inshore course.

Although in-port races do not count towards a team’s overall points score, they do play an important part in the overall rankings as the In-Port Race Series standings are used to break any points ties that occur during the race around the world.

The 14th edition of The Ocean Race was originally planned for 2021-22 but was postponed one year due to the pandemic, with the first leg starting on January 15, 2023.

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.