Race to Alaska at its finest

Published on June 15th, 2023

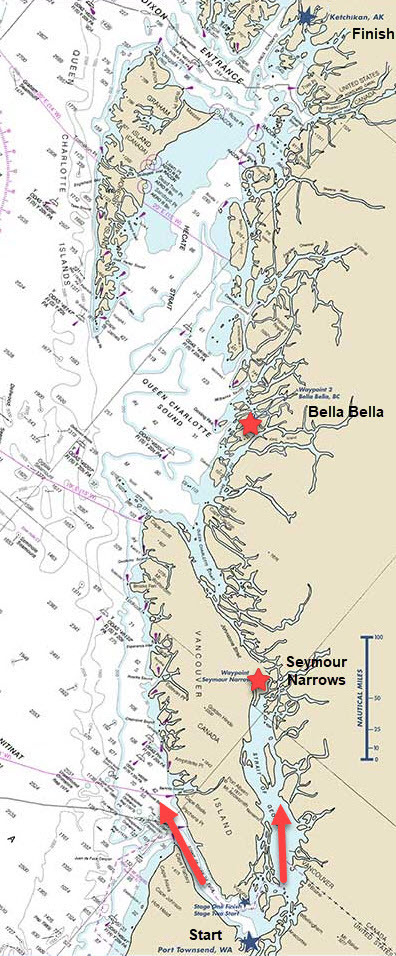

The 7th edition of the 750 mile Race to Alaska (R2AK) began June 5 with a 40-mile “proving stage” from Port Townsend, WA to Victoria, BC. For those that finished within 36 hours, they were allowed to start the remaining 710 miles on June 8 to Ketchikan, AK. Here’s the Stage 2/Day 8 report:

They say that the root cause of accidents extends beyond the moment it occurs; that when a ship sinks, a space shuttle explodes, or the USA’s entry into the Miss Universe pageant wears a 30-pound/space-themed costume in front of, apparently, the universe—there is for sure a bucket of blame that will be splashed on the captain, the flight engineers, and the nice looking lady wearing the planet on her head (respectively).

But right after hopes and prayers, there’s a hard look at what factors contributed to those people making those decisions. Like our meemaw used to say: It takes a village to raise an idiot.

What’s the straight line between Team We Brake for Whales ’s R2AK win and the 1986 Challenger shuttle explosion/2023 Miss Universe heavy metal wardrobe? Potentially only this: Team We Brake for Whales’ victory is a testament that the causal chain of custody holds true for not just failure, but the optimistic side of victory, too.

That at least today, the 40 feet of boat and 8 humans’ worth of success that hit the docks in Ketchikan is the result of compounding good decisions. Yes, this week, but Team We Brake for Whales’ victory didn’t start in Victoria, it started an indefinable number of years ago and converged between Victoria and Ketchikan over the last 5 days, 18 hours, and 59 minutes. Bravo—effing—Zulu.

Breaking down that bunch of effusive ambiguity:

Their boat:

If you were to ask 100 experts to name three words that describe the ideal R2AK race vessel, “heavy,” “wooden,” and “monohull” wouldn’t just be missing from the top ten, they likely wouldn’t make the list at all.

Apparently, our 100 experts ain’t sh#t, because TWBFW was all of those.

A 1995 custom design/build, Gray Wolf is a cold molded, cold-blooded racer/cruiser designed and built with an unstayed rig—custom made, custom paid, and custom fitted for the circumnavigating ocean racer it was built for until a decade ago when Jeanne and Evgeniy Goussev fell in love (not with each other—that happened years before when they met sailing dinghies on Boston Harbor) and bought Graywolf at first sight.

Jeanne had been stalking it online for weeks, and after cajoling Ev into a viewing appointment “We came around the corner, I saw the shape of the bow, and I was like ‘Aww sh#t, get out the checkbook. That’s our boat.’”

The decade between bow love at first sight and Ketchikan glory has been filled with racing and adventure. “Usually we doublehand, the water ballast helps a ton.” That 2,000 pound pun not withstanding and dumbing things down: sailboats heel. The wind blows on the sails, the sail/mast industrial complex acts as a lever that tips the boat over. Counteracting the inclination to tip all the way over is all of the weight in the hull that acts as a counter balance.

Adding weight and credence to “Team Counterbalance” are the weighted keel protruding from the bottom of the boat, a bunch of people sitting on the upwind/uphill side of the boat as ‘rail meat’, and (for some boats) water ballast that can be pumped from the low side to the high side to level the boat out each time you flop over and switch sides.

For Gray Wolf, it’s roughly 2,000 pounds of water that switches sides each time they tack across the wind. That’s like 10 people worth of water that you don’t have to feed or talk to that gets pumped to the high side each time you tack. The result? More miles to windward and crew who were scrambling to find charging stations once they hit Ketchikan to power up the cell phones they weren’t allowed to charge during the race.

“All of our power went to that pump.”

They never could have known it a month ago, but the upwind, bashy, and heavy conditions of the 2023 R2AK lent itself to the upwind survivability of Gray Wolf, ringing in deep and heavy at 6+ feet depth and 22,000 pounds. She was the hands-down heavyweight of the race fleet.

For comparison’s sake, Team Mojo’s race-ready F25c trimaran weighs in at 1,760—less than 10% of the weight and more than the reciprocal in complexity. Team WBFW has more weight in water ballast than Team Mojo’s whole boat.

Light and fast in the right conditions, trimarans are twitchy three-headed greyhounds. Gray Wolf is a purpose-bred, sled-pulling malamute; not as fast around the track as its jittery cousins in perfect conditions, but give it a cold night and steep hill and it’ll run miles of tundra before the greyhound can find its sweater.

Translation: TWBFW raced the boat they had, they’ve been racing it for years, and this year the Race to Alaska was tailor-made for Gray Wolf; upwind, steep, and uncomfortable.

Their crew:

Less excited than their boat about the three days of 30 knots on the nose, Team We Brake for Whales crammed a total of eight people (!!!) onboard their 40-foot boat; the largest set of humans we have ever seen enter the Race to Alaska, let alone win it.

Despite being encased in the relative opulence promised by the only winning boat in R2AK history to have varnished wood below decks, and even if they only actually baked one batch of cookies underway (still current “Cookies per mile” record holder of any team that has rung the bell in Ketchikan), despite all of that, it’s the humans that drive boats to victory—not the other way around.

Who are these eight salty souls and how did they become a crew? While unofficial team lead and now two-time R2AK champion Jeanne Goussev knew all of the TWBFW before they started, the crew was new to each other when they shoved off. The collective talent onboard was epic:

• R2AK experience: TWBFW had four trips to Ketchikan under its belt, and one victory.

• Crazy offshore experience: From Nikki Henderson’s 2018 stint as the youngest-ever skipper of the Clipper Round the World Race (she was 25, what have you done lately?), to the thousands of ocean miles they held collectively. “A lot of these teams have one, maybe two drivers. We have five offshore veteran racers so during the sh#t we could rotate through one hour helm stints knowing that whoever was driving knew what they were doing.”

• MacGyver skills, get along vibes; this is Jeanne’s husband Evgeniy’s first R2AK onboard, but he was the honorary ‘girl’ behind Team Sail Like a Girl’s 2018 and 2019 campaigns. “He built our bikes, and got our boat dialed in so we could just sail.” Evgeniy is the team MacGyver, a diesel mechanic by trade, a global sailor by upbringing. He and his family sailed from the Soviet Union to the US with a few years of wind powered globe trotting in the interim. Ev can sail, fix things, and remove then reinstall the diesel so they have options for the return trip.

More than experience, Jeanne chose their crew because of who they could trust and their underlying motivations. “From what I’ve seen, people do this race because they are running towards something or running away from something.”

They filled the boat with the former, and while they didn’t all know each other before the race start, by the end they were bonded for life. “The last two nights we were cuddling to keep warm. It was cold.”

Easy memories and smells of fresh baked cookies days in the rear view, by the last nights they were bashing upwind through the wave factory where Hecate Strait collides with Dixon Entrance and things were wet above and below.

“The V-berth was just wet, so was the middle, also the stern.”

Standing water sloshing in the cabin, the crew led a sleepless, upwind existence for days—all at a 20-degree angle as the boat heeled from ear to ear and the boat bash tacked upwind through heavy seas. Heavy boats don’t skip across waves, they belly flop, and TWBFW caught air as they flopped off each wave, their “sleeping” crew caught air below.

Cuddling to keep warm wasn’t cute, it was necessary as they all hung to stay in their bunks and within hypothermic tolerances. Type 2 fun.

The disease:

“I’m just so glad I can talk about this in the light of success.”

Despite all of the success and all of the regular mid-race adversity from waves and wind, there has been another factor in TWBFW’s win that until this sentence had been largely unnamed: MS.

Late in 2020, at age 43, R2AK champ captain of Team Sail Like a Girl, Jeanne Goussev thought she was having a stroke. She wasn’t, but it was just as scary and debilitating and it would be four months before she would know what was going on.

Until then, all she knew was that she was losing control of her own body. She lost control of her right side, lost vision in her right eye, endured ten hours of tremors at a time—all in the terrifying shadow of not knowing. There were tumors and lesions and surgeries on at least five parts of her from her brain to her spine.

She has kids, a career, a life rooted in doing things, and she hid from and hid from the world the physical upheaval for months of unknowing. Acknowledging it would make it real, and how would the world react?

“I was scared of seeming weak.” The diagnosis would come, eventually, but for four months of a failing body, “not stroke” was all she had.

It was the pandemic, Zoomlife, and work from home mandates offered a convenient anonymity. On bad days, Evgeniy would carry her from her bed to her desk and back again. For months she showered by laying down. Eventually, the diagnosis came: Multiple Sclerosis, the relapsing-remitting kind. “I’m lucky.”

MS comes in many forms, relapsing-remitting will flare up and then back off. Progressive MS would mean that her condition could only go in one direction: worse. Relapsing-remitting means that she can get worse and then better again. What brings on the worse? Stress, lack of sleep, physical exertion— three of the four food groups of R2AK.

Given the realities of her disease and the realities of racing to Alaska, Team WBFW might as well name themselves Team WTF, because why TF would someone with MS even think that this thing might be a good idea?

Her answer? A few weeks back she told us this: “I’m going to live as long as I can.”

In 2021, post diagnosis she reconvened Team Sail Like A Girl and entered the WA360 on the Melges 32 racecar that they Raced to Alaska glory in 2018. A Melges 32 is a hopped-up buoy racer that needs 100% of whatever you can give it, both mentally and physically.

“I was on a cane for two weeks. I’m not driving Ferraris anymore, but I’m going to effing sail.”

Her choice to Race to Alaska, her choice to bring her family boat, her choice of crew, the decision to bring her overqualified husband—all of those were rooted in her desire to keep going, keep doing for as long as possible.

“I get muscle spasms on a good day, living at 20 degrees (of heel) for the past three days, I got spasms in muscles I didn’t even know I had.”

To undertake such an endeavor, let alone win, she would need to surround herself with people who she could trust, in a boat she knew like the back of her hand. This campaign wasn’t about overcoming, it was about adapting. Five years since her first R2AK win she offered this perspective:

“I’m aging into a disabled body, and I’m going to keep doing what I can do as long as I can.”

There will undoubtedly be those who question the safety launching an MS-diagnosed sailor into the wilds of the BC coast. By her account, there were three times when her disease rose to the level that required attention from her crew. The biggest?

“It was a sail change, and I couldn’t get my body temperature down and I was losing control of my body.” Her team sprang into action, got her below, out of her weather-shedding/heat-trapping layers and into ice packs. “We were trying to get warm for days, but there I was, in Alaska in ice packs.”

What would happen if things took a turn for the worse? “You die with MS, not from MS.” They had contingencies on top of contingencies. They were apparently enough, they won.

***

If Race to Alaska is anything, on its best days it’s a mirror into which the eye of the beholder can stare at itself and find beauty. Today, the fairest of them all isn’t defined by seven dwarfs or the false eyelash reported to have flown off in a 40 knot gust in Hecate Strait.

From our beholding eye’s perspective, it’s in the wide-eyed, accepting triumph of the human spirit that Jeanne exemplifies. Her second R2AK victory wasn’t against all odds, off the top turnbuckle body slam smackdown of the sea or her disease—quite the opposite.

TWBFW finished first because they embraced the sum total of it all; they ended up Ketchikan victorious not by overcoming but by aligning and inspiring.

“What’s my new limit with MS? I didn’t find it.” Jeanne Goussev is an example to us all of the possibility of living to the edge of our capacities, whatever they are.

Adversity and fellowship, joy and reflection. This is Race to Alaska at its finest.

Full disclosure: Jeanne Goussev is a board member of the Northwest Maritime Center, the parent non-profit organization of the Race to Alaska. Despite/because of that, we still like her.

Race details – Entry list – Tracker – Facebook

The 7th edition of the Race to Alaska in 2023 will follow the same general rules which launched this madness in 2015. No motor, no support, through wild frontier, navigating by sail or peddle/paddle (but at some point both) the 750 cold water miles from Port Townsend, Washington to Ketchikan, Alaska.

The 7th edition of the Race to Alaska in 2023 will follow the same general rules which launched this madness in 2015. No motor, no support, through wild frontier, navigating by sail or peddle/paddle (but at some point both) the 750 cold water miles from Port Townsend, Washington to Ketchikan, Alaska.

To save people from themselves, and possibly fulfill event insurance coverage requirements, the distance is divided into two stages. Anyone that completes the 40-mile crossing from Port Townsend to Victoria, BC can pass Go and proceed. Those that fail Stage 1 go to R2AK Jail. Their race is done. Here is the 2023 plan:

Stage 1 Race start: June 5 – Port Townsend, Washington

Stage 2 Race start: June 8 – Victoria, BC

While the Stage 1 course is simple enough, the route to Ketchikan is less so. Other than a waypoint at Bella Bella, there is no official course. Whereas previous races mandated an inside passage of Vancouver Island via Seymour Narrows, the gloves came off in 2022. For teams that can prove their seaworthiness, they now had the option of the western route.

There is $10,000 if you finish first, a set of steak knives if you’re second. Cathartic elation if you can simply complete the course. R2AK is a self-supported race with no supply drops and no safety net. Any boat without an engine can enter.

There were no races in 2020 and 2021 due to the pandemic. In 2022, there were 45 starters for Stage 1 and 34 finishers. Of those finishers, 32 took on Stage 2 of which 19 made it to Ketchikan.

Source: R2AK

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.