Words to Sail By, and Live By

Published on March 2nd, 2017

The attention to safe sailing must increase as the risk increases. While the severity of risks for softwater boats vary depending on the conditions, real risks are always part of iceboating. In this report, Lloyd Roberts details the issues that hardwater sailors face.

FORWARD

We use the term ice sailors to include the whole community of those who sail on the ice. There seem to be more non-racers using the ice than racers and they are often using the same piece of ice at the same time along with the skaters, skate sailors, free skaters, bicycle riders and ice fishermen.

There is a general feeling that “touring” (non-racing sailing) is more dangerous than racing. Racing takes place on a defined, explored, area of ice. The racers sail in a somewhat predictable manner with a common goal. The opportunities for collisions in races are numerous but generally avoided by awareness and adherence to ROW rules and self-preservation instincts.

The rest of us are out for a sail on the ice. Our behavior is not so predictable and our goals vary. We may be new to the sport, or have a new craft and are trying to make it work. We may be wearing a GPS and trying to see how fast we can go. We may be actually touring, exploring the available ice. We often seem to be aimlessly reaching back and forth with no particular goal, just enjoying the unique kinesthetics of sailing on ice.

Ice sailing is inherently hazardous by nature but we all can reduce the chance of an adverse outcome with forethought, awareness (getting our eyes and minds “out of the boat”), and common sense.

Why do we do it? We do it because it is a unique and fascinating winter adventure.

RIGHT OF WAY

Safety in racing largely focuses on the ROW “rules”, different for ice racing than for soft water racing. “Right of Way” implies an imperial right and it is tempting, in the excitement of competition to use that “right” as a weapon to inconvenience rivals. Maybe water sailors do this but the high closing speeds and resulting compressed reaction time in ice racing make aggressive ROW use inadvisable.

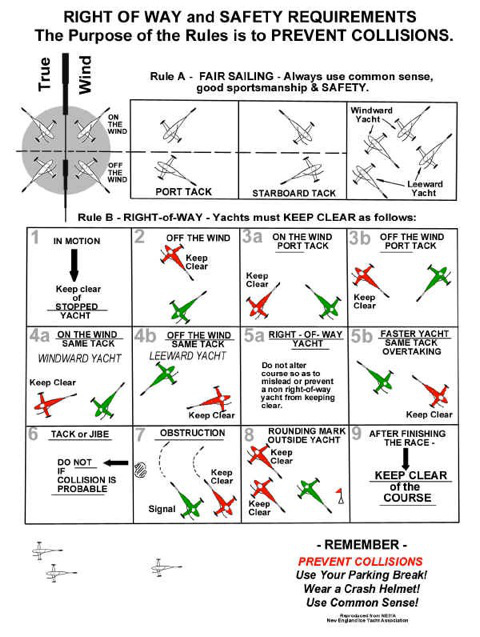

The “Right of Way and Safety Requirements” drawn by the late Hal Chamberlain based on the National Iceboat Authority Rules, should be familiar to experienced ice sailors. These are written especially for racers but should be familiar to and used by non-racers as well. These customs are designed to prevent collision by providing predictable behavior patterns for ice sailors approaching or in proximity to other sailors.

The emphasis of responsibility is on the “KEEP CLEAR” skipper. The “ROW” skipper has the initial responsibility of not altering course in a way that might confuse the “KEEP CLEAR” skipper. However, “ROW” should not sail to destruction if “KEEP CLEAR” does not keep clear. Here is where aggressive sailing by “KEEP CLEAR” can be hazardous.

Apparent aggressive sailing may of course be due to one or both skippers not seeing each other. The problems of visibility and perception are a common theme in any discussion of ice sailing safety.

The “Right of Way and Safety Requirements” follow at the end of this article. Feel free to print the graphic, laminate it, and keep it in your kit.

VISIBILITY, SEEING, AND PERCEPTION

Perception requires seeing and seeing requires visibility. In a less serious collision, during a race, the KEEP CLEAR did not see the ROW until about 8 feet away. His first thought was “what the hell is that” (perception problem) and they crashed without evasion time. ROW never saw KEEP CLEAR.

Visibility from a DN in racing trim can be difficult and often the view is through the sail window which can be compromised by reflections. Are we suggesting going back to the ‘70’s sitting position in the DN? Not a bad idea for non-racers, more comfortable too. Realistically, anything that slows down the racers is not going to happen.

Fogging of glasses, goggles and helmet visors is very dangerous and should not be tolerated. Spend whatever it takes, good goggles, vented helmet, contact lenses, etc.

Seeing requires looking. It is easy to gaze with rapture at the beauty of the sail and the antics of the tell tales or watch the ice boat beside you for some time as you creep past him. This is ice sailor’s attention deficit disorder, too long an attention span. “Keeping your eyes out of the boat” means looking around all the time, spending no more than a few seconds fixation on anything.

Despite looking you may not see a dark colored boat against a dark background, the sail may be edge on to you and not very visible. A bright colored boat may not show up against light ice in the sun. The European answer to this is fluorescent paint on the bow of the boat from mast step to bow, a very good idea. This helps peripheral vision detection and perception.

Perception is understanding what you are seeing (“what the hell is that?”), how what you are seeing may affect you, and what you should be doing about it. If at the moment you see a boat heading in your direction you also see a red stripe on your boom reminding you that you are on port tack and you are Captain KEEP CLEAR. You know it is your job to let ROW know you see him (wave, change course sufficiently) and you will miss him. If you are not racing you may be deep in ice reverie in ice heaven but you still have to periodically deal with other boats and all of the ROW customs apply.

HAZARDS OF TOURING

We have dragged home ice boat wreckage at least a half dozen times in the past 30 years, including many years of racing, but never from a racing accident. I have luckily never been really injured, just pretty sore a couple of times. Most non-racing accidents are solo affairs. They are usually due to ice hazards, wind hazards (too much), or mechanical failure. Any ice big enough for touring in the literal sense of sight seeing is going to have hazards, guaranteed.

It is not smart to sail alone even on ice “known” to have no hazards. It is suicidal to sail alone on unknown ice or on big ice even though some of it has been recently sailed on. Other than a short trip out to the race course we use the buddy system. The buddy system means sticking together like glue with another ice boater and maintaining visual contact.

On a large lake a buddy system of four skippers is better. If something happens requiring help one skipper stays with the disabled party, the other two go for help. No one is alone.

Top speed is not necessary or desirable while touring (it is the trip, not how fast you cover the ice). Sit up, slow down, enjoy the scenery, keep an eye out for hazards and day dreaming tourers, again, eyes and mind out of the boat.

HAZARDS OF THE ICE

Ice, wonderful stuff, not only presents many patterns, colors and textures which give it character, but it may be too thin, reasonably thick but structurally unsafe, have holes in it for no apparent reason, be pressed together into ridges, pulled apart into open leads, or simply absent in unexpected places. Blessed is the lake covered with a uniform sheet of ice with no defects. This lake is usually small, you don’t need big ice for a big time.

Just as it is foolish to sail alone, it is almost as bad to come to a lake with boaters already on it and not inquire about hazards. If “there aren’t any”, don’t believe it, follow other boats until you get the lay of the ice. Still, use the buddy system. On a lake of any size if you have a problem and the sail comes down you disappear. You were sailing alone despite others on the ice.

New black ice usually does not cover the whole lake all at once. You can have nice 3 ½ inch thick ice transition to 1 ½ inch thick without any clue on the surface as seen from the ice boat. Snow drifts on new ice may insulate it so the ice under the drift is dangerously thin. Snow covered new ice is extremely dangerous.

Ice expands sideways as it freezes until it buckles into wrinkles called pressure ridges or reefs. These are always dangerous as one edge over rides the other often breaking it into small pieces that will not support you or your boat. Usually a ridge can be crossed somewhere after exploration on foot. Never sail across a pressure ridge no matter how benign looking unless you have just seen someone else do it right in front of you, and even then use caution.

Be aware that pressure ridges may change from safe to unsafe in minutes. When in doubt get out, park, and explore on foot. Sometimes “pressure ridges” pull apart, these open leads are especially treacherous, even if you “know where it is”.

Many lakes have areas where, year after year, there are open spots, maybe way out away from shore. Local knowledge is very important and is the reason we tend to sail the same lakes season after season.

Frequently there is thin ice near points, islands, and shallow spots (like launch ramps) due to local solar warming of shallow water. These also tend to repeat year after year. Streams entering or leaving can be counted on to have thin ice near the mouth. Likewise but not so obvious, narrows between islands can have currents that undermine the ice.

Navigational buoys usually mean shallow water, beware.

We sometimes sail on larger lakes with large areas of open water (we would rather not). Be wary not only of the visible water but also the likelihood of open leads extending away from the open water. These can be sneaky because your attention is drawn to the open water and you do not look in front of you.

A nice sheet of ice on a large lake with a lot of open water may blow away from the land and then break up or it may break up from on shore wind and wave action. Local knowledge is vital.

THE VIRTUE OF SAILING AROUND BOUYS

Some feel that racing is what iceboating is all about and spend all their time doing it, going around little red buoys like moths around a candle. Racing is very exciting, highly addicting, and the only way to learn how to sail an ice boat well. Get advice and coaching from the faster skippers, they will be happy to help you.

If you have questions about ROW, ask. DN racing has gotten very serious, sophisticated, expensive, time consuming, and rather daunting to the new ice sailor who often states “I just want to sail”. OK, but that sailor will probably never learn to sail downwind in light air, which always seems where the launch area is at the end of the day.

Informal racing is the key here, you don’t even need to think racing, just put out a couple of traffic cones for windward and leeward marks and sail around them. Lacking cones, use fishing houses. (With respect for tip ups and people. If you hit a tip up, stop immediately and reimburse the fisherman.) The important thing is to break out of the easy pattern of just reaching back and forth all the time. It takes at least a season to get the hang of sailing down wind. Some never get it.

PERSONAL SAFETY

SPIKES: You have to have traction. Spiked track shoes are the ultimate in traction and lack of warmth. Golf shoes are warmer. Insulated boots with ice fisherman strap on things (“DeIcers” recommended) are warmest and OK on clean ice, they are not so good in snow.

HELMETS: You absolutely need a helmet. Years ago we saw an iceboater while wearing spikes slip, fall, and lay his scalp open. Another, not wearing spikes, slipped just standing still and knocked himself out. Ice is harder than the hardest of hard heads. The “Joffa” skiing helmets are very popular with the racers because they are very light which is vital for the recumbent DN racers and the face opening is very wide for good visibility. The lack of weight is due to a relatively thin outer shell and skimpy shock absorbing padding.

A Snell approved motorcycle helmet is designed for impact resistance at highway speeds with hard objects like ice boat parts and ice, not just packed snow on a ski slope. Yes, they are more expensive. What are you brains worth? The weight is not much of a problem if you are sitting up in a civilized manner in touring mode. If you race, build up your neck muscles (see Appendix; “Skipper Care”). A properly fitting helmet is nice and warm too. Buy your goggles at the same time so they fit the helmet.

ICE PICKS AND THROW ROPES: Most of us now carry a pair of handles with spikes in them on a string around our neck (these are commercially available or you can make your own with dowels and nails). These are for clawing your way up onto the ice if you go swimming. Wet ice is very slippery. You can also carry a throw rope in a small bag or on a small reel on your waist. This you can use to haul someone out of the water or get yourself hauled out by your buddy. Your main sheet may save a life.

CHANGE OF CLOTHES IN YOUR CAR: A complete change of warm clothes would be pretty nice if you get wet, wouldn’t it?

PHYSICAL CONDITION SAFETY: Ice boating is strenuous, especially carrying and setting up the boats, and particularly trying to get a boat out of a hole in the ice. It is annoying to find you cannot hold your head up after sailing a short time. It is really annoying to be laid up for a couple of weeks after throwing your back out lifting ice boats or their parts. Regular daily year round stretching and muscle tome exercises will prevent these problems. See “Skipper Care” in the appendix.

HYPOTHERMIA: It is easier to stay warm than to get warm. Overall hypothermia can happen, especially if you have been swimming. Get ashore and get warm. At least change out of the wet clothes, if really cold get into a tub or shower. If really really cold, like unable to stand or losing consciousness, get to a hospital, this is a medical emergency, do not even try to walk around, activity can kill you.

A face mask or full face enclosed helmet is a must for all but spring sailing at above freezing temperatures. Hands and feet seem to present the most problems. Hands spend a lot of time pulling on the sheet which doesn’t help circulation. Snowmobile mitts and gloves would seem to be a good idea but most of them don’t do the job. The best arrangement in our experience is insulated deer, elk, or moose hide “choppers” (Cobella’s or LL Bean) mitts a size larger than you wear and an inner pair of thin but warm gloves that you can leave on when adjusting rigging, changing runners, setting up the boat etc. The XC skiers have some nice thin gloves with leather palms.

If wearing track shoes look for Gortex outer socks that keep the wind out and even stay dry when wading in puddles. Divers foam neoprene socks work well too. Again the shoes should be a size or two too big so you can wear a couple of layers of socks.

The ultimate anti cold weapon is the catalytic warmer envelope (iron and salt) which gives off heat for 6-7 hours. These are available at sport shops and often at gas stations in ice fishing country. They come in hand and toe patterns. They cost about $1.50 a pair, worth every penny. When it really gets cold these will keep your pinkies toasty warm all day, really.

IMMERSION: If you haven’t been swimming you probably will. The U.S. Air Force requires all air crews to pass immersion drill exercises, it has been suggested that at first ice we should do the same, someone please organize this and lead the way. Not a bad idea, but I doubt we will get universal participation.

Anticipation and forethought should be almost as good as doing it. There has recently been a report from an immersion guru that once in the water you have about 10 minutes of consciousness and action before hypothermia gets you and you should spent the first minute getting used to the cold water, orienting yourself, and planning action. My personal experience and that of some others is that if you get out fast enough you don’t get totally sopping wet, a big plus.

The most common situation is sailing into a small spring hole or pulled apart pressure ridge you did not see. The ice boat tips over and often some part of it is on the ice for convenient climbing out. You may end up under the sail which can inspire panic. The ice at the edges of such defects is usually thick enough to support standing weight and often the boat can be extracted and sailed home promptly with due regard for the sheet freezing. This is easy: you go in, you get out, you get it out, you sail it home, you change and warm up.

If the boat is damaged get someone else to sail you home and make sure you are dry and warmed. Let others take care of the wreck. If you were sailing alone you could be in big trouble. Apply warm fluids inside and out (bath, shower). It is important to be chaperoned in the post swim interval as hypothermia can rapidly lead to mental impairment and confusion unapparent to the wet person. Incoherence and inability to stand is a medical emergency, call 911, do not let the cold person try to warm up by attempting to walk etc. Get them out of wet clothes.

Sailing onto thin ice for some distance and breaking through is more complicated. It is important to get out, spread your weight out on the ice by not getting up, and claw your way back from whence you came on thicker ice. A moment or two for orientation is in order here. Extraction of the ice boat can be complicated needing ropes, boards, boats, etc. If an immersion suit is available and seems useful it should be used by someone familiar with its use, practice is needed, preferably in the summer. Preparation goes a long way here.

Early and late in the season I often carry a 12 foot plank on the truck, usually used for getting on the ice at a thin edge. It would be very handy for thin ice rescue. A windsurfer hull with ping pong paddles, the paddles having spikes on the other end of the handle, is advised by Leo Healy and sounds pretty good. The NJ ice boaters have a tin “john” boat on retractable trailer wheels that is hauled to the ice by car and on the ice with an ATV. But the boat/trailer can haul all the regatta paraphernalia out to the race site including the wind break for the race committee, hot meals, lawn chairs, etc. More things to play with.

It is possible to get out of the water without ice claws by getting your body horizontal in the water and breast stroking up onto the ice. The late Larry Hardman did this easily (at 1 AM by moonlight and zero degrees), he says he just popped out onto the ice like a seal. The hard part was waking up the occupants of a nearby house who were astonished by the ice encrusted black snow mobile suit clad apparition. They took him in and plopped him a bath tub.

Skaters usually have warning they are on thin ice by cracking preceding break through. My experience (skating on known thin ice over thin water) is that a skate breaks through and trips you so you fall forward automatically distributing your weight over the ice. The skate has all your weight on a few square inches. The only problem here is your feet get wet and the laces freeze so you can’t get the skates off. A pocket knife plier combination tool works well here and is often handy for ice boating.

In summary, go in, think, get oriented, get out, get help, get dry, get warm.

Source: Chickawaukie Ice Boat Club

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.