Mini Transat: Riding the route

Published on November 7th, 2017

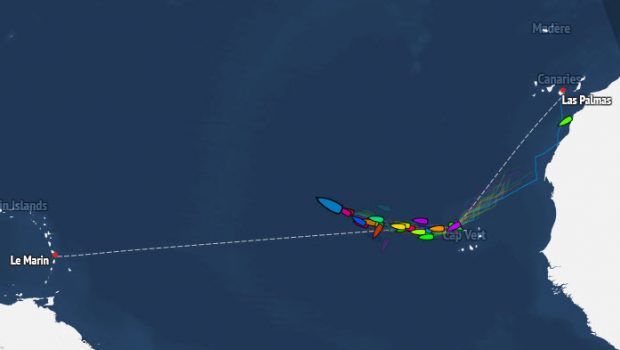

(November 7, 2017; Day 6) – Virtually in single file, the solo sailors competing in the Mini-Transat La Boulangère are attacking their oceanic crossing on a WNW’ly heading, slightly above the direct course. In these conditions, with the routing that has stood the test of time since leaving Gran Canaria, wisdom recommends favouring the layline. However, there already appear to be some mavericks on the Atlantic chessboard.

Powered up in the Atlantic, the solo sailors know that speed is likely to make the difference in this first third of the race rather than route options. As such, it’s important to organise oneself, assess the most beneficial moments to sleep, eat and entrust the autopilot with the helm, whilst ensuring you take back control at the right time to give the boat some added pep.

What counts is not so much the peaks of speed but the daily average. A consistent performance is the name of the game in the eyes of a solo sailor. In this exercise, those sailors familiar with the Atlantic have a certain advantage.

In the prototype category, Ian Lipinski (Griffon.fr), Jörg Riechers (Lilienthal) and Simon Koster (Eight Cube Sersa) all have at least two ocean crossings to their credit. For those for whom this is their first time, you have to learn to harness your emotions and find the right rhythm so you’re neither too fast nor too slow.

Old hands of the Mini-Transat are fond of saying that there’s a psychological barrier to overcome, that of the third or fourth day out after you’ve left the land behind you. Some don’t need that to prove their metal.

Indeed, Patrick Jaffré (Projet Pioneer) has had to bring his boat to a complete standstill to consolidate his rudders, which were kicking up without warning after becoming delaminated. Incidentally, he was helped in this endeavour with a pot of resin supplied by a fellow Mini sailor, who diverted his course specially.

Charlotte Méry (Optigestion – Femmes de Bretagne) must still have a few issues with the inboard end of her spinnaker pole, given the lowly speeds of her Bertrand design. Their plight has boosted Kéni Piperol (Région Guadeloupe) up the ranking and he is now in sixth position.

In the production boat category, the return of Tom Dolan (offshoresailing.fr) to fourth position has a lot to do with his wealth of experience. Without making a song and dance about it, Tom is regularly a little faster than his immediate rivals. Nothing spectacular, but by dint of a few extra tenths of a knot, the Irish sailor is gradually clawing back the miles, day on day.

Of note too is the gamble being attempted by Tanguy Bouroullec (Kerhis Cerfrance) and Pierre Chedeville (Blue Orange Games – Fair Retails), who have both opted to put in a gybe to reposition themselves further to the south.

In Dakar, Erwan Le Mené (Rousseau Clôtures) has officially signalled his retirement to Race Management. The state of his transom meant that a quick and reliable fix was not possible and the sailor from south-west Brittany has decided on the safe option. Meantime, Dorel Nacou (Ix Blue Vamonos) has left the Moroccan coast. The sailor from Marseille is likely to feel rather alone, but he’s seen other hardships over the years.

At Mindelo amid the Cape Verde archipelago, life continues for those affecting repairs. Two solo sailors are ready to set sail again: Julien Héreu (Poema Insurance) and Vedran Kabalin (Eloa Island of Losini). Ambrogio Beccaria (Alla Grande Ambecco), who made landfall there at 07:00 UTC this morning, has repaired his bowsprit and has announced that he’ll head back out to sea as soon as his twelve-hour time penalty has elapsed. Even though his overall ranking hopes have been dashed, the young Italian sailor has not finished with his Mini-Transat. He still has two thousand miles to show what he’s made of.

Position report on November 7 at 15:00 UTC

Prototypes

1 Ian Lipinski (Griffon.fr) 1,467.3 miles from the finish

2 Simon Koster (Eight Cube Sersa) 68.4 miles behind the leader

3 Jorg Riechers (Lilienthal) 83 miles behind the leader

4 Romain Bolzinger (Spicce.com) 144 miles behind the leader

5 Andrea Fornaro (Sideral) 150.4 miles behind the leader

Production boats

1 Erwan Le Draoulec (Emile Henry) 1,636.8 miles from the finish

2 Clarisse Crémer (TBS) 20.9 miles behind the leader

3 Tanguy Bouroullec (Kerhis – Cerfrance) 45.1 miles behind the leader

4 Tom Dolan (offshoresailing.fr) 85.3 miles behind the leader

5 Benoît Sineau (Cachaça 2) 86.7 miles behind the leader

Class news – Race news – Tracking – Facebook

Race Facts

· 21st edition

· 4,050 miles to cover between La Rochelle – Las Palmas in Gran Canaria and Le Marin (Martinique)

· 81 skippers at the start

· 10 women

· 11 nationalities

· 20 years: age of the youngest skipper in the race: Erwan Le Draoulec

· 62 years: age of the oldest skipper in the race: Fred Guérin

· 25 prototypes

· 56 production boats

· 66 rookies

· 15 ‘repeat offenders’

Background

With an overall length of 6.50m and a sail area pushed to the extreme at times, the Mini Class offers incredibly seaworthy boats. Subjected to rather draconian righting tests and equipped with reserve buoyancy making them unsinkable, the boats are capable of posting amazing performances in downwind conditions… most often to the detriment of comfort, which is rudimentary to say the least.

The Mini Transat has two legs to carry the fleet from La Rochelle, France to Martinique, West Indies. The leg from La Rochelle to Las Palmas de Gran Canaria is a perfect introduction to proceedings before taking the big transatlantic leap.

The first leg starts on October 1, with the fleet thrust into the Bay of Biscay which can be tricky to negotiate in autumn, while the dreaded rounding of Cape Finisterre on the north-west tip of Spain marks a kind of prequel to the descent along the coast of Portugal. Statistically, this section involves downwind conditions, often coloured by strong winds and heavy seas. Making landfall in the Canaries requires finesse and highly developed strategic know-how.

The second leg begins on November 1, with the solo sailors most often carried along by the trade wind in what tends to be a little over two weeks at sea on average. Due to a storm, the fleet is being routed south to Cape Verde before heading west. At this point, there’s no way out: en route to the West Indies, there are no ports of call. The sailors have to rely entirely upon themselves to make Martinique.

Source: Aurélie BARGAT | Effets Mer

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.