The science behind your sail trim

Published on May 17th, 2020

by Tom Whidden, North Marine Group

One of the goals for our book, The Art and Science of Sails, is to connect the theoretical with the practical. An understanding of the physics of aerodynamics will help us better trim and set our sails. To illustrate this, I’ve chosen a seemingly obscure topic – induced drag and how to minimize it – by splicing together a few excerpts from my new book.

As a tactician, I need to ensure the boat is fast. Otherwise, we’re not going to win, regardless of how well I do my job. And, since the main was always front and center for me, I was constantly studying it, ensuring my mainsail trimmer was doing his/her job. I hope the following will help you better understand the connection between the science and sail trim—and there’s plenty more detail in the book.

********

By far the largest and most destructive drag for sailing performance is induced drag. The root cause of induced drag is the changing of the direction of the air flow by the foil. With airplane wings that change is downward; with a sail it’s to weather. The change in flow direction is the beginning of the process of lift.

So, induced drag is a direct result of the creation of lift. In more technical terms, induced drag is the varying coefficient of lift (Cl) across the span. In other words, the differences in lift across or over the total area of a sail or wing cause induced drag.

How does induced drag relate to real life on a sailboat? Assuming the boat is well trimmed and properly set up, about 80 percent of the total sail area will experience relatively constant Cl. However, in the aftermost 20 percent of the sail, the velocity of the flow rapidly decreases; and with it, the lift. The rapidly changing Cl results in significant induced drag, some on the leech and some at the head and foot. This induced drag forms the vast majority of the total drag.

There are two variations of induced drag:

• off the trailing edge (leech)

• off the tips (head and foot)

Induced Drag off the Leech

These are vortices, spinning counterclockwise-off that trailing edge. A deeper head section, compared to the bottom, minimizes the flow of air trying to find the shortest path from the high-pressure windward side to the low-pressure leeward side.

Leech twist is very significant for the optimization of upwind speed. It’s been said that the only reason to have a front of a main is to be able to attach the leech area to the mast! The leech of the main not only ensures that the air bent around the front of the main is allowed to exit with the least interference (induced drag), but also to help steer the boat.

So, how should the trimmer adjust the leech to best attain the above two goals while sailing upwind? With a well-designed and relatively new main, the answer is to sheet the main until the top telltale (preferably hanging off the back of the top batten) just begins to stall. If it’s constantly stalled (hidden to leeward), it’s a sign drag is too high. The lift-to-drag (L/D) ratio is lowered. If the telltale is flying straight back or there is an excess of backwind, it’s a sign that the sail could be sheeted tighter to allow the boat to sail closer to the wind. In this case, the L/D ratio is reduced for the opposite reason.

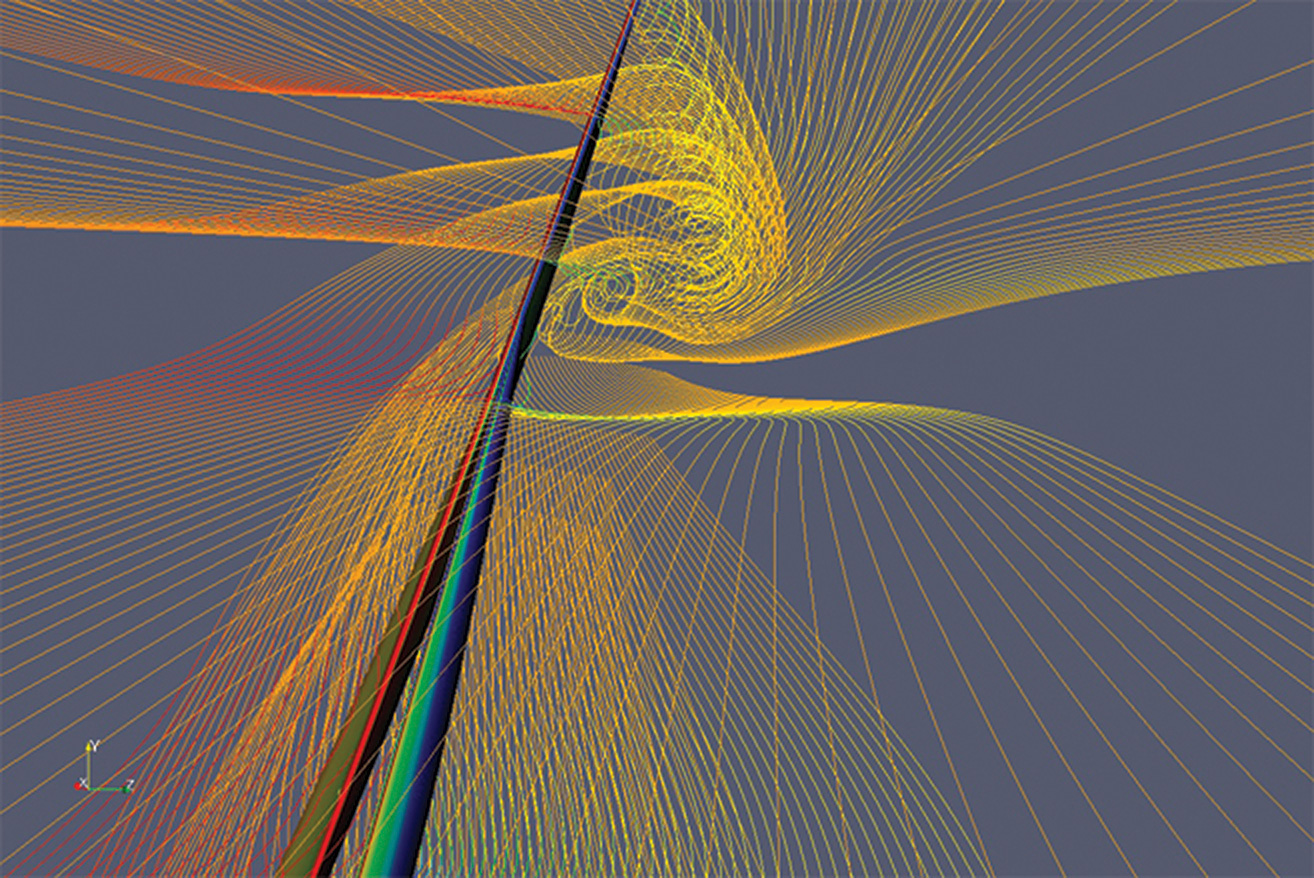

This screen shot, from a RANS-code CFD analysis, illustrates the tip vortices emanating primarily from the top leech of the main on a fractional-rigged boat. The orientation is looking back at the top of a rig and sails from just to leeward and forward of the onset flow.

Induced Drag off the Head and Foot

The second variation in induced drag is tip vortex. On a plane, these flow off the ends of the wings; on a sail, they flow off the head and foot. There is a pressure difference, or delta, from the lee side of the sail to the windward side. Nature abhors pressure deltas. It’s why we have wind. And, it’s why the flow on the high-pressure side of a sail wants to escape over the top or end to help equalize this pressure.

Almost all modern race boats employ a fractional rig. At the hounds, the main’s chord on the fractional rig is still quite long and therefore helps shed the headsail’s tip vortices. On a masthead rig, the tip vortices of the headsail are matched with the tip vortices of the mainsail. Not good!

*****

We cover this topic (and many others) in much more detail in The Art & Science of Sails (Revised Edition), written by myself and Michael Levitt. If you enjoyed this short overview you’ll enjoy the book even more.

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.