R2AK Time Machine Day 3/25

Published on June 18th, 2020

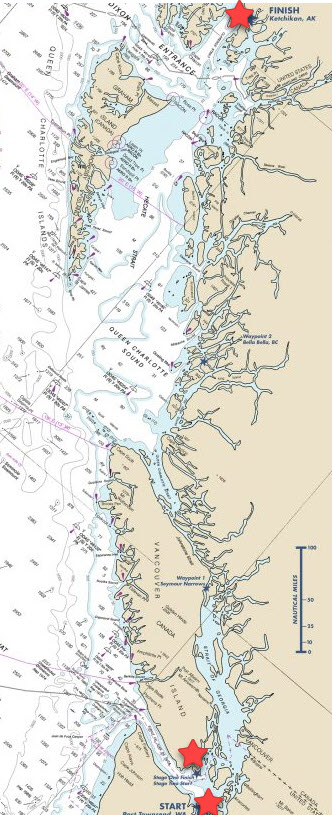

For five years, the Race to Alaska, a 750-mile course from Port Townsend, Washington to Ketchikan, Alaska, had proven that not every game is on the blacktop and how kids can still play in canyons.

And just because COVID-19 cancelled the 2020 edition, that doesn’t mean the Race to Alaska High Command can’t, for 25 days, share their fondest memories from the previous races. They can, and they are. Enjoy!

Let’s understand something. As we begin to talk about first finishes, we cannot ignore Team Elsie Piddock, the first team to ever finish R2AK; a forever and unchangeable fact.

They happen to also have the slowest time of any first finishers, but, let us remember, led the charge into an unknown landscape which had oddsmakers laying an over/under between “never” and “when pigs fly.” Here’s a video made by someone else, because we were too busy, cheap, and sleep-deprived to get one put together. Now, onto MAD Dog.

There was a moment in Campbell River when Jake and I (Race Boss) looked at each other in fear, realizing Jake and the rest of the finish line crew may not be able to beat Team MAD Dog (above) to Ketchikan, even if they headed to the airport right away.

MAD Dog is the fastest finisher ever, beating its nearest competition by over 7 hours. They are fast, and fast enough to cause one unnamed pro team to pack it in early because the writing was on the wall as far south as Victoria.

One of my favorite factoids about MAD Dog? The off-watch crew had to sleep on the high side, but the team didn’t account for the fact they were going to sail so damn fast that the high side switched on an average of every 20 minutes. They arrived in Ketchikan so sleep deprived Randy Miller said they’d likely have run onto the rocks if the race was any longer.

READ:

2016 Day 4: Hard Charging into the Record Books

While the R2AK nation slept sound in the knowledge that they would rise in plenty of time to check the tracker and box out a spot in the online queue for the coveted feed of the Ketchikan harbor cam, Team MAD Dog Racing was hurtling in the night on a downwind screamer, 23 knots downwind through the great wide open of Dixon Entrance.

Full throttle in the darkest night that the crew had ever seen. No stars, no moon, no lights from an uninhabited shoreline, just black stallion racing into the spray filled darkness. “We couldn’t tell where the horizon started, it was too dark to know where the boat and the water were.”

By the time we all woke up and checked the tracker, then checked it again, they were close. Oh my god close. All over Ketchikan you could hear forks hit plates in a mid-bite mind blow that had people breaking into a dead sprint, breakfast left half eaten and steaming on the table so they could get to the finish line on time.

You know that sweaty nervous panic you get when you oversleep for a job interview? Same thing happened all over town as folks threw on clothes and danced the dance of people trying to put on pants and move at the same time.

One driver clocked the M32 catamaran along the waterfront road south of town, his car barely keeping pace in an impromptu race within a race that only he knew he was losing. How are they that fast?

Team MAD Dog Racing was within sight of the finish line and they were still sending it, fast. Even the press was surprised, some slipping in to the back of the crowd in the hopes that their competitors wouldn’t notice.

Their two red hulls nosed over the finish line at 7:13am, and unless our fading memory of public school math once again miffed the complex +1 of the time zone calc, Team MAD Dog finished the R2AKin 3 days, 20 hours, and 13 minutes, smashing last year’s top finish by…well, a lot…way more than a day…you do the math.

They were greeted on the dock by a crowd still hustling down the gangway, Colin Dunphy’s mom who exploded in the emotion of complete celebration and unfettered relief—hard to have a dry eye when an exhausted racer is embraced by the love and pride of his exhausted mom who had likely slept more than her dry-suited son, but not much. So proud.

They nailed the landing, rang the bell, had the rare experience of clearing customs with smiling officers who seemed to want to shake their hands as much as they wanted to look at their passports. They posed for pictures, pressed the press, double-fisted coffee and beer until adrenaline shrank to number two or three on the ranked list of their bodily fluids, before Randy received the R2AK’s version of a NASCAR shower and beer sprayed towards faces in a well-deserved celebration.

They made it. More than that, they crushed it, and landed on the dock with deeply satisfied smiles that masked their exhaustion. Triumph would win over sleep for a few more hours, but only barely.

The cameras and microphones asked the questions we all wanted to: Did you sleep? 20 minutes at a time, maybe every 12 hours, in a bivvy sack, in their drysuits, arms crossed to wedge themselves into position on the rack that felt most secure. Yes, it was eerily like a body bag. In one hand they’d grasp a knife in case they had to cut themselves out in the event that their dreams turned into the least exciting/most terrifying kind of wet.

Tacking upwind cut the sleeping shifts short, and no matter how short the interval they’d wake, emerge from, stow the bivvy, move to the high side, and then crawl back in to catch whatever sleep they could grab before it happened again. How often? There are a lot of narrow passages, and with a fast boat sometimes hours would go by without 10 minutes between maneuvers.

How did you avoid driftwood? Mostly, these sailing Jedi used the force. “When it gets dark the driftwood seems to disappear.”

Aren’t you tired? How are you still standing? The answer to that was met with laughter and an answer to the next question. They saw whales, no bears, were blown away by their luck in the tidal gates, amazed and satisfied that the work they had done to battle harden their spindly mess of high tension speed to the rigors of a non-stop charge through the wild coast had been successful.

“We raced the boat hard beforehand to identify components that needed strengthened” You mean you broke a lot of stuff in some other races? “Yeah.”

Family and friends lingered after the crowd subsided and the sunburnt and weary trio sank into the first hot meal they’d had in four days that hadn’t been rehydrated. After so much time hanging onto a bouncing net in pitching seas, they struggled to walk up the ramp, or stand still enough to focus on the menu above the counter. Dry land had become foreign to them.

After all hands sailing the cell service void of the R2AK’s back nine, they’d been out of touch with the outside world for days, and like anyone in and around the R2AK, it wasn’t long before they shifted their eyes to the tracker checking on teams and getting excited, beginning the process of piecing together the fatigue-filled memories into a cogent story and then started getting excited about the progress of teams that impressed them.

They traded stories of their favorites. Their first? Team Hodge. Hodge was a garage built 8-footer that made the run in stage one. Hodge. There couldn’t have been a team in the race so opposite to the skittery rocket they’d just ridden to Ketchikan.

They were accomplished sailors on a high twitch speed machine. Hodge built his own slab-sided plywood wonder out of a potentially appropriate three sheets, painted her blue, and then cut down some tarps for sails. They wore technical clothing, Hodge wore a sailor hat in a manner that was in the blurry no-mans land in the war between irony and sincerity.

Still, after the race of a lifetime and a new world record, they didn’t pause between their bacon filled bites to gush full-mouthed enthusiastic about how impressed they were that he made it across stage one, or how infected they were by his spirit and enthusiasm. They have hearts as big as their skill.

They worked through the fleet: Team Jungle Kitty’s location brought excitement and memories. “That’s a tricky spot,” as did the four-way battle that was shaping up for the steak knives. “We’ve got a race!” With each bite they relaxed, their fatigue rising to the surface little by little and their excited chatter was replaced with longer and longer stares and sleepy satisfied smiles.

Ian Andrewes broke the silence with a question that revealed just how total had been their focus on the goal: “Wait, is there an airport here?”

Team MAD Dog Racing’s charge north was impressive, and one that had many in the sailing world shaking their heads. “This will end badly,” was a word of warning from a skeptical expert in the know. The M32 was a high stakes gamble. A gust and a capsize and it would be game over. Short of a nearby tugboat there would be no way to get the big cat back on her feet. Their plan—ditch the rig, get her right side down and start pedaling.

Each of them wore dry suits kitted out with life jackets, DSC marine band radio Personal Locator Beacons, and some inflatable noodles they could inflate to make it easier for rescue crews to see them. These weren’t maverick yahoos with a death wish, they took safety as seriously as they did their sailing. And while they never needed it, their ace in the hole was a mark of all pro.

As they trundled off to some much earned sleep, the rest of us shook our heads, checked our math, shook our heads again, checked the tracker, and got excited for the next wave of gritty excellence headed north like a freight train.

Four teams in striking distance, two monohulls each being chased by their own Cerberus. They’ll pass soon across Dixon entrance, and all of us will be adjusting our expectations ever earlier. The race has just begun.

WATCH:

Race details – Previous races – Facebook – Instagram

What was to be in 2020:

What was to be in 2020:

Race to Alaska, now in its 6th year, follows the same general rules which launched this madness. No motor, no support, through wild frontier, navigating by sail or peddle/paddle (but at some point both) the 750 cold water miles from Port Townsend, Washington to Ketchikan, Alaska.

To save people from themselves, and possibly fulfill event insurance coverage requirements, the distance is divided into two stages. Anyone that completes the 40-mile crossing from Port Townsend to Victoria, BC can pass Go and proceed. Those that fail Stage 1 go to R2AK Jail. Their race is done. Here is the 2020 plan:

Stage 1 Race start: June 8 – Port Townsend, Washington

Stage 2 Race start: June 11 – Victoria, BC

There is $10,000 if you finish first, a set of steak knives if you’re second. Cathartic elation if you can simply complete the course. R2AK is a self-supported race with no supply drops and no safety net. Any boat without an engine can enter.

In 2019, there were 48 starters for Stage 1 and 37 finishers. Of those finishers, 35 took on Stage 2 of which 10 were tagged as DNF.

Source: Race to Alaska

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.