R2AK Time Machine Day 15/25

Published on June 30th, 2020

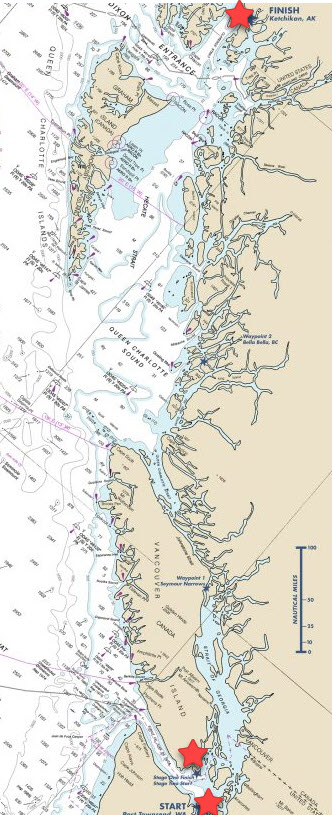

For five years, the Race to Alaska, a 750-mile course from Port Townsend, Washington to Ketchikan, Alaska, proved that journey trumps destination, and while COVID-19 cancelled the 2020 edition, the Organizing Authority is, for 25 days, sharing their fondest memories from the previous races. Enjoy!

Karl Kruger was the first person to complete the R2AK on a stand-up paddleboard. He is the only person to complete the R2AK on a stand-up paddleboard. It is also the longest distance a SUP has raced in all time, anywhere, like ever. Enjoy these moments and also see the next improbable, impractical, and beautiful goal Karl is pointed towards at: www.karlkrugerofficial.com

This is the second time in R2AK reflections that we compare a tremendous human feat to dancing about architecture. The fact is the greater the accomplishment; the fewer choices of metaphors exist to relate it to humans like ourselves. It’s a little like reaching into the metaphor cupboard to describe space travel—it’s a pretty bare cupboard. And it’s a great metaphor, so worthy of repeat appearances.

READ:

2017 Day 15: A dance about architecture

Someone much smarter than ourselves once said, “Writing about music is like dancing about architecture.” While we’ll admit to a contrarian attempt to learn the Tudor Revival Tango just to prove them wrong, we take their point. Each medium that offers the chance of human expression creates a language onto itself—each with their particular resonance for the portion of sublime that it animates in that chakra-like space between our hearts and our heads. Or something like that.

Today, the Ode to Joy Chorus, the Guggenheim, the hundreds of cheering dockside fans in Ketchikan, and the thousands more across the internet welcomed Karl Kruger/Team Heart of Gold to Ketchikan and into the rare air where human accomplishment resonates so broadly; SUP to Alaska in 14 days and change. Cheering, shaking heads, open mouths, F-bombs, Emoji, emoji, emoji, hallelujah in every sense of the word.

Even without the confusing exercise of describing Karl’s arrival through architecture, the language at our disposal only gets us so close. That was true from the time our cameras intercepted him in a post-cheeseburger moment at the Shearwater Resort, to the awkward dockside exuberance of a crowd of people, including us, who wanted to be near him but knowingly lacked a meaningful bridge between excitement and understanding.

We stood on the dock or stared at the screen and words surfaced from our mouths that we knew both true and inadequate: “Amazing,” “Unbelievable,” “Congratulations.” We beamed and stood too close for too long, like a four-year-old infatuated with a birthday party magician—heartfelt, but lacking a credibility to elevate the praise beyond a boundless appreciation.

On the dock or on the internet, we needed to say these things at the same time knowing we had nothing to say. Our words were less of a conversation and more chance for the audible echoes of our beings to get as close as possible to the wonder that is Karl Kruger. “Way to go” was sincere, inadequate, and as close as our wide-eyed brains could get to meaningful. He was there with us, but 750 miles past any experience we could wrap our minds around.

Unless you’ve also paddled a board to Alaska, how could you even come close to creating a frame of reference? You might have been on a paddleboard, but when was the last time you were on a one for longer than an afternoon? You might have been alone, but two weeks? You might have gone ultra-light camping but probably not to the “food wafers instead of food” level where every ounce might be the difference between making it to Alaska and a sluggish board, strained muscles, and the kind of injury that could leave you throbbing and foodless in the middle of a cold nowhere.

Unless you’ve augmented your time on paddle boards with big wall climbs, through hiked the PCT, surfing, kayak touring, and silent monastic retreats, how do you get even close to the never ending “Stroke, breath, stroke, breath” existence of Karl’s last two weeks?

When was the last time you were alone, really alone, Karl Kruger alone, for two weeks? The occasional bewildered boater, once in a while heartfelt text from home, as many cheeseburgers as possible, but mostly alone; without even the distractions of media that have become the sonic wallpaper to our lives. Music, internet fact checking and re-watching the West Wing because the new season of Handmaid’s Tale isn’t out yet—all absent and replaced by Nature 360.

Imagine how you would rattle around in your head given that endless supply of nothing, how the lesser angels of your soul might question every big and little decision of your past and near future—the mounting doubts of your life, your job, your marriage, this race, why are you here? The quiet can serve as a megaphone to doubts, especially in the midnight of a storm-whipped sleep, laying cold in the damp gravel of the high tide line. Every gust threatening to shred the only thin shelter you have, every creak and rustle sounding more and more like the bears you saw earlier.

Your blisters are growing, and that creek on the map went dry so now you dig in the hopes of the water you need to stay stay alive and wash the film from those damned wafers out of your mouth. This is optional. Stroke, breath, stroke, breath

On top of the Mt Everest-level physical feat Karl just accomplished is the metaphor defying feat of negotiating his psyche during those 750 optional miles of cold feet and weary muscles. Here the frame of reference is truly challenged to evolve past 4 year-old/magician, and maybe because it is so rare to see victory without a loser. As he stepped from his board to the dock, Karl’s excited and placid demeanor wasn’t that of someone who just won in the classic sense of competition.

When he rang the bell in victory, there wasn’t an ounce of ego driven celebration, no bloody-mouthed dance over an opponent still flat on the mat. He didn’t kiss the ground, utter his “never agains” then offer the crowd his hardship confessional; sharing the worst of it to validate the experience through applause. He hadn’t conquered the coast, the finish line wasn’t his salvation.

He hadn’t left it all on the field, won by KO, extra innings or penalty kicks. Karl’s race had always been with himself, and rather than the dramatic punctuation of a buzzer, the final point, or nosing across 6 minutes ahead of the next guy. His victory emerged from within, seemingly by better aligning his being with the everything happening both inside and outside of head. The waves, the weather, himself. His body was weary, visibly smaller than when he left, but his core seemed unmoved and if anything larger, more settled, more rooted.

For many teams, the finish line takes on a “Ketchikan or bust” persona, and they arrive with tattered sails, hasty repairs, wet gear, and exhaustion. Their plan is to ring the bell and then sort out the legacy of mayhem left by all of the corners cut in the final days. Ketchikan is their reset button. In contrast, Karl paddled in with all intact, pulled a bone dry jacket from his bag and met the solitude shattering throngs of cameras and fans with the same easy eyed smile he had when he left Port Townsend. He was finished, but his version looked closer to complete.

Karl always knew he could do it, so did his family. Most of the rest of us fell somewhere between skeptical and lacking the frame of reference broad enough to include that a SUP to Alaska was even a possibility. Seriously, remember the first time you heard SUP and R2AK in the same sentence? Regardless of how far the scales of your opinions tipped towards skepticism, if you’re like us, your judgment was stayed at least momentarily by a healthy dose of “Really? That’s a thing?”

As much as Karl stayed the same the rest of us transformed with each stroke, gale, wafer, and cheeseburger that brought him closer to the finish. Our disbelief never wavered, even now it’s mostly intact.

But whatever skepticism we had was displaced with the kind of enthusiasm that started with a shake of the head, a smile as we tucked in the tracker for a reluctant good night, and building to the hoots of enthusiasm, punching your co-workers in the shoulder, hugging whoever was nearby as he rang the bell, wiping tears of joy as he embraced his wife and daughter for the first time. He had done it. This apparently was a thing and for whatever reason it mattered.

When we started the Race to Alaska, we hoped that it would inspire us all to connect with the best parts of our possibility. That in a world dominated by contrivance and commercials we might provide a forum to reconnect people to adventure in its purest form. Without rules, motors, and as close to the nature-state wildness of a stretch of untamed coastline, connecting all of us to everyday heroes inside of us all who might consider the challenge first and the size of the applause a far off second or third.

If there were an embodiment of the architecture dance of the full scope of awesome we hoped the race would encompass, Team Heart of Gold gets as close to pure “that” in a way we never imagined possible until we were reveling along with all of you as he crossed the finish line. What could be more audacious, hardcore and simple than a paddle, a board and as little as you can carry?

Cram as much skill and deep determination as will fit in a human, dip the blade again and again until Ketchikan is in sight and impossible is a few horizons behind. For the people on the dock, the thousands watching from the internet, the superfans who lined the beaches to cheer him along the way, and people just hearing about it for the first time this was a rare type of incredible. Mind blowing, heart expanding, reality shifting incredible.

A guy in Ketchikan encountered Karl and his story for the first time in the fading echoes of the cheering dockside celebration. He recovered from his double take to offer his abridged version of that journey through skepticism.

Guy: “I kind of don’t believe that you did it.”

Karl: “I’m here to tell you that I did.”

Stroke, breath, stroke, breath.

The language of SUP might seem simplistic, but the layered nuance of taking one to Alaska might be the kinesthetic Haiku we’ll all be unpacking for years. Inside its four syllables are the depths of our possibility.

Stroke, breath, stroke, breath.

WATCH:

Race details – Previous races – Facebook – Instagram

What was to be in 2020:

What was to be in 2020:

Race to Alaska, now in its 6th year, follows the same general rules which launched this madness. No motor, no support, through wild frontier, navigating by sail or peddle/paddle (but at some point both) the 750 cold water miles from Port Townsend, Washington to Ketchikan, Alaska.

To save people from themselves, and possibly fulfill event insurance coverage requirements, the distance is divided into two stages. Anyone that completes the 40-mile crossing from Port Townsend to Victoria, BC can pass Go and proceed. Those that fail Stage 1 go to R2AK Jail. Their race is done. Here is the 2020 plan:

Stage 1 Race start: June 8 – Port Townsend, Washington

Stage 2 Race start: June 11 – Victoria, BC

There is $10,000 if you finish first, a set of steak knives if you’re second. Cathartic elation if you can simply complete the course. R2AK is a self-supported race with no supply drops and no safety net. Any boat without an engine can enter.

In 2019, there were 48 starters for Stage 1 and 37 finishers. Of those finishers, 35 took on Stage 2 of which 10 were tagged as DNF.

Source: Race to Alaska

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.