R2AK Time Machine Day 17/25

Published on July 2nd, 2020

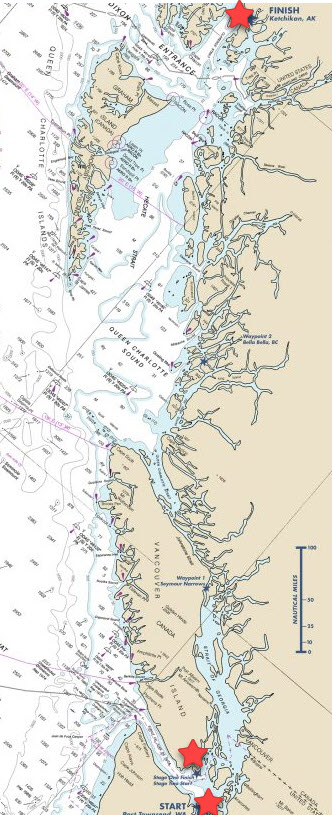

For five years, the Race to Alaska, a 750-mile course from Port Townsend, Washington to Ketchikan, Alaska, proved that journey trumps destination, and while COVID-19 cancelled the 2020 edition, the Organizing Authority is, for 25 days, sharing their fondest memories from the previous races. Enjoy!

You have 16 and 116. One is the age of a crew member, the other of the gaffed-rigged prawner known as Ziska. Then there is the owner, Stanford, over 50, who spent more than two years restoring said vessel, which has never seen an engine, and who captained her up the Inside Passage in R2AK 2019.

The experience of sailing Ziska is described by the aforementioned 16-year-old Odin as, “a horrific time commitment.” Stanford, who knew a little more about what he was committing to, countered with, “More time and more miles, but that’s what it takes, that’s what sailing is, that’s okay.” Here enters our last descriptive number: the recursive 16, which is the number of days it took them to finish.

Ziska holds finishing records for oldest boat, youngest crew member (pretty sure that’s true), and most miles to destination at 1,281 miles (for a 750 mile race).

Take a look at Ziska’s original 2019 bio to get an idea of motivation, and then look at the 2020 Team FAST bio, which is Odin’s response to sailing a 116-foot vessel all the way to Alaska. (Hint: the word “fast” is in the team name.)

READ:

Day 17: Team Ziska: 16 days and 100 plus 16 years

After weeks of intense experience onboard with the next mile, sail change, and chance to sleep being the only relevant markers of time, racers hitting the finish line often have a hard time remembering what day it is. Not as common was the phenomenon that everyone dockside experienced yesterday: in the silence of Team Ziska rowing the final yards, it was hard for anyone watching to remember what century it was.

R2AK has had plenty of wooden boats hit the finish line, but nothing that comes as close to the shear heft and beauty of Ziska’s 1903 Morecambe Bay Prawner…or Lancashire Nobby, or whatever the hell it’s called. It was as stunning as it was heavy and hard to row as it was exhausting for the crew.

Team Ziska’s step off their boat and on to the dock was a lot like the finish line moments from 16 days and four years of the teams that have come before, but with a transparent tinge of the full body, “So effing done.” Beyond their boat, theirs was the story of rebuild and rebirth, the wood stove that burned almost every night, and it was clear that they had absolutely nothing left—not even enough to celebrate a job well done or to do much more than mumble “Hello” even knowing the whole world was watching.

We couldn’t help but love the unbridled and unfiltered honesty of their R2AK moment of done – unbridled in the sense there was nothing left to harness. They left it all out there.

Beyond the 100% tired that reduced their comments to just above pantomime, when their 116 year-old black hull declared their finish as it crossed the Thomas Basin line in silent slo-motion, it was hard to appreciate the bizarro timeline truths that emanated from the single moment some 16 days of racing, 2 years of restoration, and 116 years since construction in the making.

The team hit the finish line and seemingly and immediately dazed in what it all meant. They were done for sure and for finally, but the moment was only a blip on the continuum of the stories held in their vessel’s ancient hull.

For sure they were tired, that much was obvious. 16 days of 4 hours on, 4 hours off watch schedule meant that all four of their crew hadn’t had more than 4 hours of sleep in a row since they left Victoria. Being clear, “not more than 4 hours in a row” really means “probably not more than 3.”

Four humans breaking the day into watches of 4 hours on/ 4 hours off means that while they might have officially had 4 hours of below deck rest, that includes the 15 minutes before they had to wake up and get dressed, the 20 minutes it takes anyone to fall asleep after swapping out, or the all-hands calls any time the fan hitting shit of gale force winds and the crew has to amp to 11 and to make sure the wet part of the boat stays below the water.

There’s no tape to play back to get an accurate read on how much sleep they actually got, but to stay on the ignorant version of innocent we are 100% not looking up the UN limits for when sleep deprivation officially becomes torture.

A hard pressed crew with realistic hopes of winning have 4-5 days of all-out effort. Team Ziska had 16. Someone once asked the question whether it was harder to win the Race to Alaska or to gut it out farther back. While we only have a half-idea of the various variables that might aggregate into what “harder” means, Team Ziska’s Race to Alaska has to roll prominent into at least the top five in any and all categories. Some options:

· Most miles: 1,285 that their onboard GPS tracked them from tack to ever loving tack that carried them through sometimes 160 degrees. Significance? Imagine the wind coming from the 12 on a clockface. With their canting keels, canting masts, and high twitch carbon sails and spars, the front runners might be able to trim their sails and get within 35 degrees to the wind—roughly sailing along the path of the hour hand at 1:20-ish. Ziska? Right around 2:45. You could math out the difference between how many more miles you’d have to zig-zag at 2:45, but in the race just run, it was the difference between a straight line 750 and 1,285 miles… 535 more if you’re doing the bare minimum of maths.

· Heaviest: Compared to the rest of the fleet, at 15 tons, Ziska has the density of a dying star. Their bowsprit is 400 pounds, their rudder is solid steel and estimated at 3,000. Giving context, the weight of Team Pear Shaped Racing’s entire trimaran is exactly 3,000 pounds. Fully rigged. 116 years old and a trimaran’s worth of rudder—then there is the weight of the firewood they burned every night…Ziska is a different kind of R2AK.

· Shakedown cruise: While not unique, Team Ziska joins the ranks of racers who made their trip even harder by only having sailed their boat for about a month before the race. More than dialing things in, those sails were the rolling beta test for how things worked and the things still left to do from their two year restoration. None of them had sailed it before they tore it apart so they could put it back together. This was all fresh, entirely anachronistic, and the sheet leads still needed finalized.

If you ask him, more than just being hardcore in the wood fire every night/hope we don’t have to row kind of way, the story of Team Ziska wouldn’t be complete without a mention or two of Odin Smith, Ziska’s youngest crew member. At 16 years and a technically important few months younger than the other two 16 year olds who finished this year, Odin is also the youngest racer to ever complete the race.

Not shy of speech, Odin became a bit of a spokesperson for Team Ziska and did at least two interviews for newspapers, and for a day or two he was all over Canadian TV news shows. Before they left the dock in Victoria he was already looking past their soon-to-be finish and declaring himself captain of a contender for 2020. He even talked a drysuit rep into selling him one for $100, maybe 10% of its cost and including delivery. Kid can talk.

How was Odin’s Race to Alaska? “I think I’m never going to do it again in a boat like that.” He admits that it was a cool boat that was great for the heavy air days, days of gales and 20-foot rollers. Days that were lighter were miserable, especially when they needed to row. Plus, as a 16 year old that self identifies as a hot stuff sailor with speed demon tendencies, he was in it to race.

It killed him that they stopped as much as they did, anchoring 5-6 times to wait for the tides, and going to shore twice—one was to treat an eye infection that had blocked his vision in one eye. Didn’t matter; consequences be damned, this is a race and what do doctors know anyway.

It might have been more than an enraged swollen eye roll when he realized mid-race that Ziska’s competition were rowboats and outrigger canoes. Still, once he settled into that reality, his response to learning that Ziska had bested all of the small craft? “Cool.”

Odin will tell you that 100% it was harder to do the R2AK on Ziska than on any of the performance boats. “It’s such a horrific time commitment. It’s almost unnecessary.”

It’s been a long two and a half weeks. Sleep deprivation, physical exertion, and tight quarters tend to grind on crews, especially those who are newly formed and new to a boat. Reading between the lines, at least for Odin, the flight home couldn’t happen fast enough. Were there good parts? “There were a lot more whales than I was anticipating. One time we going through 25 knots of breeze and big rollers, and an orca jumped out of a wave like 100 feet in front of us. We saw whales all the time. The boat has a spirit of its own. It seems to attract wildlife.”

How was rowing? “Absolutely horrible. It’s not a boat that needs to be rowed.” In apparent agreement with Odin, and an outright refutation to the R2AK’s foundational premise, Ziska is slated to be outfitted with electric pod drives when it returns to Port Townsend.

What’s he looking forward to doing when he gets home? “Sailing, but on a more modern boat, like my keelboat, or Martha.” Martha is a Port Townsend based schooner that Odin crews on periodically, and is indeed more modern; her keel was laid in 1907, a full four years to the modern side of Ziska. Like happiness, and stock valuation, modernity is measured on the margin.

Odin volunteered his one sentence summation of the whole experience: “Great heavy weather boat, horrible light air boat, sucks to row, yay.” Finally, R2AK’s version of:

“How was school?”

“Fine.”

For the boat and the crew, Team Ziska’s is a story of preservation, and at the same time of a rebellious rebirth of spirit when launched as a racing departure from the local fishing fleet, and born again when a 19 year old sailed forth from England, crossed an ocean or two, and ended up in America. That the boat lives on and has inspired some of their crew to restore her, and at least one of their crew into next year’s R2AK (yes, that hasn’t changed), this race was as much a culmination as it was a precursor.

To hear both stories of Team Ziska is to remember. Partly it’s remembering a time of 100-years-ago technology; partly it’s remembering what it’s like to experience something incredible through the confident lens of a newly minted 16 year-old. Both seem like enviable and simpler times, at least in the abstract, and mutually exclusive—at least for Odin. Either way it should get on the cover of Wooden Boat, impressive boat and an incredible effort.

Race details – Previous races – Facebook – Instagram

What was to be in 2020:

What was to be in 2020:

Race to Alaska, now in its 6th year, follows the same general rules which launched this madness. No motor, no support, through wild frontier, navigating by sail or peddle/paddle (but at some point both) the 750 cold water miles from Port Townsend, Washington to Ketchikan, Alaska.

To save people from themselves, and possibly fulfill event insurance coverage requirements, the distance is divided into two stages. Anyone that completes the 40-mile crossing from Port Townsend to Victoria, BC can pass Go and proceed. Those that fail Stage 1 go to R2AK Jail. Their race is done. Here is the 2020 plan:

Stage 1 Race start: June 8 – Port Townsend, Washington

Stage 2 Race start: June 11 – Victoria, BC

There is $10,000 if you finish first, a set of steak knives if you’re second. Cathartic elation if you can simply complete the course. R2AK is a self-supported race with no supply drops and no safety net. Any boat without an engine can enter.

In 2019, there were 48 starters for Stage 1 and 37 finishers. Of those finishers, 35 took on Stage 2 of which 10 were tagged as DNF.

Source: Race to Alaska

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.