R2AK Time Machine Day 21/25

Published on July 6th, 2020

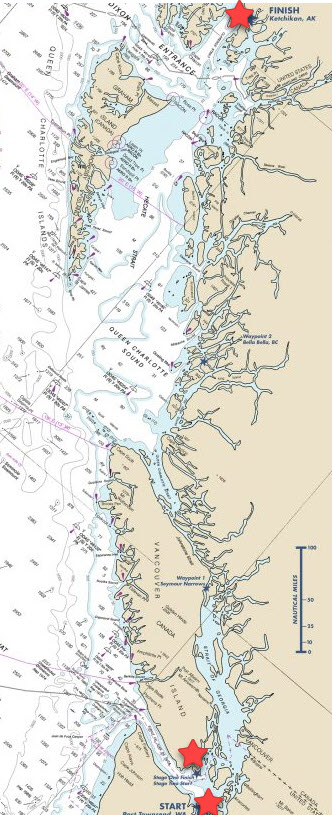

For five years, the Race to Alaska, a 750-mile course from Port Townsend, Washington to Ketchikan, Alaska, proved that journey trumps destination, and while COVID-19 cancelled the 2020 edition, the Organizing Authority is, for 25 days, sharing their fondest memories from the previous races. Enjoy!

Let’s talk 2016 Solo Kings. We’ve got two videos and a daily write-up featuring big characters in R2AK. France’s Mathieu Bonnier of Team Liteboat (above) and local boundary pusher Thomas Nielsen from Team Sea Runner. They each are classic examples of the soloist plunge into the joys and abject fears of racing alone up the Inside Passage.

As Thomas goes north, sleep evades him, and when he does finally reach Ketchikan, he tells the tale of howling voices calling him to rocky shores, pleading for him to turn and head towards inevitable destruction. He’s our own homespun Odysseus narrowly avoiding the Siren’s Call.

Also, you won’t see it here, and I never told you, but when Mathieu finally reached the golden drenched shores of Ketchikan, he stepped from his boat, leaned toward me, gently grasping my shoulder for a little assurance and balance to whisper in my ear, “Do you know where there is a doctor? I must see a doctor. I think so much rowing has created permanent nerve damage in my ass.”

Immortal words from a titan of adventure. Enjoy the perspective.

READ:

2016 Day 18: Solo Kings

The time between Team Liteboat’s finish and Team Sea Runners was less than a day—two solo attempts but the similarities end there. Different boats, different men, different languages, both attempts to use their campaigns to create breakthrough moments for the boats.

That’s right, we’re not just the weird kid in the corner anymore, the R2AK is a king maker. All hail kings Liteboat and Sea Runner—the 22nd and 23rd winners of the 2016 R2AK.

The first same different to cross the line was Team Liteboat: not the shortest boat in the race, but a slight rowing tri without an onboard “Angus cabin-coffin” (TM). With the paddle board gone, Liteboat is the odds on favorite to be the smallest boat that will finish.

Mathieu Bonnier lives in the mountains of France, he’s rowed across the Atlantic, he’s rowed the Northwest Passage, and according to his math he’s rowed 98% of the R2AK.

He arrived at 2145 local time—visibly smaller both in his physical frame (by his accounts, he shed 8-12kg from an already slender stature)—and his demeanor, which was neither the jubilation of the triumphant nor the wry “thank god” of the never-agains.

Fresh off the boat Mathieu was a hollow exhausted and dazed concerned. This was a veteran of big water crossings and it was clear from his demeanor and desire to head to the hospital to address a couple of issues, that this had taken him to the limit.

“This is a very hard race, very complicated race, especially Cape Caution…big waves from the Pacific, mixed with two currents, very confused seas. Rowing is very difficult…”

His injuries were unclear, but related to the non-stop sitting in salt water (“Boat butt,” a nodding head offered helpfully while looking around to make sure his diagnosis was heard and appreciated. Yep, “Boat butt.”) and the repetitive days on the oars. He wasn’t sure, but was worried about nerve damage.

His average day on the oars was 12 hours, his last was 17. Seventeen hours on the oars as the capstone to nearly three weeks on the water—zut alors! “I think I rowed something like 95%? 98%? Something like this.” Le whoa.

His boat was a one-off experimental modification of one of Liteboat’s floor models. Like any experiment, success is sometimes defined by what didn’t work. Positive lessons from negative experiences. His sailing rig? Too small. He’d enlisted a relative pro-sailor to help out with that, and the rig they designed was based on the wind data from last year.

They took the power down a few pegs to compensate for Mathieu’s nascent sailing ability. His sailing chops are three months old (he’s from the mountains), so despite the fact that his boat appears to have training wheels, he didn’t want a rig big enough to get him into trouble.

It didn’t, but maybe too much so. The light winds that did come were maybe strong enough once in a while, but often it was a sailing rowing combo that got him through the miles.

His tent? Tentative. It was a tippy and nervous dance to erect the onboard accommodations in the only space that a person could stand, while at the same time he was standing in it, and standing for the first time in hours. Crawl in, eat some dehydrated food, catch an uncomfortable sleep (while hoping the waves didn’t build and soak the tent), wake up, break it all down, and row.

Upon arrival he was immediately embraced and adopted by the good folks in Ketchikan who came out in force. They were thrilled and spoke slightly louder and slower than normal with big facial expressions and more hand gestures in the hopes that it would ease the divide between the two languages.

They took him home to the first stable bed he’d had in weeks, then took him to the doctor to have the various ravages of the race examined. He’d made it, but the course had taken its toll.

There doesn’t seem to be much about Team Sea Runner’s voyage that Thomas didn’t record, post to social media, or his audio blog. Thomas was busy and willing—his trip was a self-actualized Truman Show.

Thomas Neilson, the lone runner on Team Sea Runners started with the same raw data as Mathieu, but rather than a downscale rig in anticipation of a repeat of 2015’s storms, he shoved his chips all in and bet on a big rig. He was going to sail all the way; fast, light, and furious on a new fangled boat that was ready to take the west coast by storm.

His chosen steed for the R2AK: the Seascape 18, an ascendant European one design fleet racer. A fast planing monohull with a big rig and a small cabin, Thomas and the brass at Seascape thought it was a match for the spartan race cruising of the R2AK.

Last year was big weather, perfect for the wind powered skipping rock that Thomas throttled up to 25 knots during a windy sea trial earlier this spring. This year, not so much. He stuck to his plan, sailing all but three hours or so of the course, hanging on when the sails were only eking out a knot or two.

“I think I only had three days of real wind.” The Seascape would have to take the west coast by calm. His tactic would shift from his stern mounted bike to just sailing, slow and sporadic whenever the breeze allowed.

“I spent a lot of time from 1.8-2 knots.” Slow speeds as constant as he could make it, often matching Liteboat’s human powered pace. On at least one day the tortoise and hare covered 20 miles in roughly the same time. He only went to shore once (Kelsey Bay), the rest of the time he was sailing, or asleep, or sometimes both.

“I slept sailed for at least four nights.” Sometimes it was intentional, sometimes he just nodded off while clipped in. “I woke up multiple times with the boat just sailing along. If you fell off that boat it would just keep sailing forever.”

While Google drive it ain’t, and the boat/rock/driftwood early warning system is still in development, the fact that it might have sailed itself in the right direction for two hours of sack time is a testament to exhausted sailing and a well-designed boat.

“You know, the weather we had…in a normal race the committee boat would have either cancelled because of too much wind or not enough. We had that for the entire race.” Looking at the footage taken by a frustrated and exhausted Mr. Nielson, the Jekyll and Hyde aspect of this year’s R2AK didn’t just roll off the duck’s back.

It alternately soaked and baked in, a binary misery machine that dunked and dried—constantly annoyed regardless of what cycle. A primal scream all the way to the end, right as he was on final approach into Ketchikan’s small boat harbor that bears Thomas’ name, the guy on the break water caught a fish and the Seascape caught the line.

So close, one more speed-bump. Seems fitting to have one final frustration literally 100 feet from done.

While he and his sponsors would have liked to finish farther up the fleet, after nearly three weeks since Port Townsend, his endorsement of the boat stands. He shared a little of his accolades for his craft (“Great boat”) before whipping out jokes about Newfoundland and declaring an interest in finding some trouble. Shore leave well earned, the commercials can come later.

Farther back in the ever diminishing fleet, the theoretical departure of the sweep boat is happening at any minute, and four teams are still trudging north: One solo and three doubles to go before the R2AK packs it in and tumbleweeds out of town. Hurry well, little boats. The sweeper cometh.

WATCH:

Race details – Previous races – Facebook – Instagram

What was to be in 2020:

What was to be in 2020:

Race to Alaska, now in its 6th year, follows the same general rules which launched this madness. No motor, no support, through wild frontier, navigating by sail or peddle/paddle (but at some point both) the 750 cold water miles from Port Townsend, Washington to Ketchikan, Alaska.

To save people from themselves, and possibly fulfill event insurance coverage requirements, the distance is divided into two stages. Anyone that completes the 40-mile crossing from Port Townsend to Victoria, BC can pass Go and proceed. Those that fail Stage 1 go to R2AK Jail. Their race is done. Here is the 2020 plan:

Stage 1 Race start: June 8 – Port Townsend, Washington

Stage 2 Race start: June 11 – Victoria, BC

There is $10,000 if you finish first, a set of steak knives if you’re second. Cathartic elation if you can simply complete the course. R2AK is a self-supported race with no supply drops and no safety net. Any boat without an engine can enter.

In 2019, there were 48 starters for Stage 1 and 37 finishers. Of those finishers, 35 took on Stage 2 of which 10 were tagged as DNF.

Source: Race to Alaska

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.