Marcel Van Triest: The Seventh Man

Published on November 8th, 2015

The Jules Verne Trophy is a prize for the fastest circumnavigation of the world by any type of yacht with no restrictions on the size of the crew. No limits, just go for it…exactly what Francis Joyon (FRA) plans to do when he and five crew set off this fall to break the record of 45 days 13 hours 42 minutes 53 seconds.

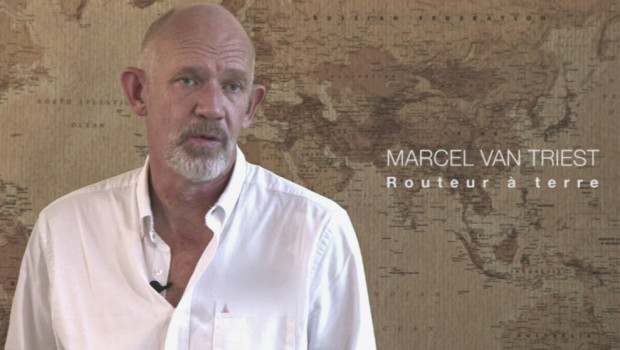

Joyon will be skippering the 31.5m VPLP-designed IDEC SPORT, and will be assisted on land by Dutch router Marcel Van Triest. Staring at the screens at his home in the Balearics, the seventh man will follow the weather patterns to advise the team on when to begin and the best course along the route.

Marcel was alongside the team that holds the current record… here he shares his insight:

Marcel, what is the real problem for a router in the Jules Verne Trophy?

We need to look for fast conditions, but which aren’t boat-breaking. Understanding that we can only see ten days ahead at best, there are two goals: the time it takes to get to the Equator and the time to Good Hope (tip of South Africa). In the South, you take what you are given and there’s no way out: further south, you have the ice, further north the areas of high pressure. Boats like IDEC SPORT sail very quickly, but can’t jump across weather systems in the Indian and the Pacific. After that, the climb back up the Atlantic is down to chance and you have to get lucky.

Francis Joyon is sailing with a short-handed crew of just six men aboard in all. Does that change anything in comparison to the bigger crew that Franck Cammas had on this boat or in comparison to the thirteen sailors with Loîck Peyron?

Yes. When you are establishing a route for a solo sailor, it’s not the same as for a crew… here, we’re in between the two. That will be one thing I’ll need to focus on. You can’t send a small crew into nasty conditions, as you need to ensure they remain on form and they are going to be very busy. They are going to have to get the timing right to carry out manoeuvres.

One of the major questions is how to handle high speeds over a long period. How does it feel on board?

Speed in itself isn’t a problem. Sometimes it feels like you’re hardly moving, when you’re doing thirty knots. What is very stressful is when you are in boat-breaking conditions. When you wait for the boat to slam down – it gets on your nerves…but being becalmed is too, when you sit there imagining your rival zooming along at thirty knots, while you remain frozen to the spot.

You get used to the speed in the same way as when driving at 140 km/h (90 mph) on the motorway. You can even get used to 180 km/h (110 mph)… but you can’t do that in a built up area or when the route is blocked! It’s the same on a multihull. You can sleep at ease at 35 knots on flat calm seas and enjoy yourself… but it is stressful at 17 knots when the sea is nasty. The strong gusts can become a nightmare, when it’s your turn at the helm.

How will you be working with Francis?

We’re going to have to adapt our way of working, as this is our first time together. Personally, I’m not keen on the phone. With all the noise aboard the boat, there is the risk of not getting all the info and you can’t record it and listen to it again. So I tend to work with drawings with notes on.

We work on the basis of twice a day, or more when needed. We exchange e-mails. In the Doldrums, it’s all the time and sometimes, there’s nothing to say. In the last Jules Verne, I only called up the boat twice in 45 days.

How much time can be shaved off the 45 and a half day record? Do you think they can reach the 40-day barrier?

They could reach it. It’s possible, I mean. If they are really lucky with a weather opportunity that is more or less perfect, allowing them to get a good time to Good Hope, if there’s not too much ice, no technical problems and the Pacific allows you to sail further south shortening the journey… but then again, you can always lose it all again off the Falklands.

You need to be lucky throughout in fact, but there is a margin in the Jules Verne. I should add once again that you don’t have to take five days off the record. One hour is enough. The chances are higher of smashing this one rather than the Atlantic record, where you can stay on stand-by for ten years in New York without finding an opportunity to shave 3 or 4 hours off the record.

You might just as well ask me if it’s possible to win the lottery. But, yes for the Jules Verne, it’s feasible, but 40 days would be very tough.

We imagine the router sleeping beside his computer and satellite phone, going through the race 24 hours a day. Is it really like that?

Definitely, yes! There’s as much stress as on board, except that I can take a shower when I want and eat better stuff. But it has to be very stable for me to get more than three hours sleep in one go. I wake up at least once a day to check things. So the rhythm is very much like aboard the boat. Having said that, it’s a little less extreme in the Jules Verne than during solo attempts, when you are responsible for the life of the only sailor aboard the boat.

What do you like about working as a router?

There’s just you, land and a blank sheet. It’s a gigantic game of chess. It’s fascinating to work through all the possibilities and when you get a good result from your ideas, it’s very satisfying. You start off with general ideas. You work on them and gradually build up your route.

Often in this type of attempt, there are two or three key moments. If you identify them on time and deal with them, you can do it. One of the two calls I made to Loïck during the last Trophy concerned the route down under Australia. By changing ever so slightly the sea state parameters, I could see there was a way through in the south.

Loïck thought I had gone crazy, telling me there was already a 10m swell. But if they had followed the initial northern route, the boat would have been held up close-hauled. I said to him, ‘Think back to when we were twenty and looked for a heavy swell. It’s impressive, but it’s not dangerous. You will find it tough for twelve hours, but you will make a huge gain’.

That is exactly what happened. I love analysing the weather on that scale. And as I have raced around the world five times, I can well imagine what it is like. It’s a bit like being aboard.

NOTE: The Jules Verne Trophy’s starting point is defined by an imaginary line between the Créac’h lighthouse on Ouessant (Ushant) Island, France, and the Lizard Lighthouse, UK. The course from there leaves the capes of Good Hope, Leeuwin, and Horn to port before crossing the starting line in the opposite direction to finish.

Source: IDEC Sport

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.